Ancient fossil proves some pterosaurs preferred eating plants over meat

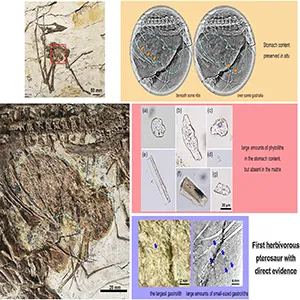

A fossil from northeastern China has settled a long-running debate about what pterosaurs ate. Inside the ribcage of a Sinopterus, researchers discovered a compact, three-inch stomach mass packed with plant microfossils and tiny stones.

The research provides direct evidence that at least one pterosaur species ate plants. That simple gut snapshot shifts a long-running debate from “maybe” to “yes.” It also offers a rare glimpse into how a flying reptile processed tough food.

Proof in the stomach

The work was led by Shunxing Jiang, Ph.D., at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). His research focuses on pterosaur anatomy and evolution.

Scans place the mass between the ribs and belly bones, indicating where the stomach would have been. The team confirmed the find through careful imaging and sampling from the slab – not from loose rock.

One part of the mass looks like a storage area, and the other reads like a grinder. The front section matches a proventriculus – the food holding chamber ahead of the stomach in birds, based on its size and position.

The rear section matches a gizzard, the muscular chamber that grinds food using tough walls and trapped grit. That pattern is common in plant-eating birds, and it helps break down hard plant parts.

How the team tested the idea

The researchers used CT-style imaging to confirm the mass was in place before burial. They also examined the surrounding rock to rule out contamination.

The experts applied micro-computed laminography (MCL) – an X-ray scanning method for flat fossils – to map tiny stones and textures throughout the slab. This approach revealed where items sat relative to bones with fine detail.

Only the stomach mass yielded plant silica particles; no comparable particles appeared in the nearby matrix, arguing against modern dust or lab contamination.

The team also recorded numerous tiny stones clustered near the back of the mass. The two largest stones sat near the front, which may mean they were swallowed close to the time of death.

Plants and stones together

The mass held 320 phytoliths – microscopic silica bodies made by plants inside their tissues. Some match forms that are seen in woody plants, and others resemble shapes known from grasses and ferns.

The same section held many gastroliths – small stones used in a gizzard to grind food during digestion. Their mix of sizes suggests repeated use for abrasion rather than a one time accidental swallow.

Only one pterosaur had shown stomach stones before, the filter feeder Pterodaustro. That earlier paper documented clusters of stones inside its gut, which were interpreted as grinding aids for hard food.

Ruling out meat and bugs

If Sinopterus had eaten fish or small vertebrates, at least some bones or scales should remain. Multiple Rhamphorhynchus fossils preserve stomachs full of fish remains – a clear piscivore signal in those animals.

Soft prey like worms would not call for heavy grit. The many stones make sense for plants, which resist digestion and benefit from grinding to release nutrients.

Insect rich meals usually leave fragments of tough exoskeleton. None appear here, which weakens an insect diet for this individual.

Redefining pterosaur diets

Direct gut evidence in pterosaurs is rare. Most past work inferred diet from skull shape, teeth, or habitat, while confirmed stomach contents have been limited to a few specimens, often with fish.

Tapejarid pterosaurs, the group that includes Sinopterus, have been suspected plant eaters based on skull mechanics. A paper on a close relative argued that its head and jaw build fit tougher plant parts.

This specimen now links that idea to what was actually eaten. It shows plant parts inside the body, along with the tool set needed to grind them.

Reading the plant record

Phytoliths carry hints of their source plants. In this case, the forms varied widely, which suggests a mixed plant diet rather than a single food.

Some forms resemble those in broadleaf plants, and a few echo shapes common in grasses. Diversity at that scale points to varied feeding in a rich Cretaceous landscape.

Similar plant silica has been recovered from the gut of an early bird called Jeholornis. That analysis found that this long-tailed bird ate leaves, confirming that silica bodies can track real diets in deep time.

Bigger picture of pterosaur life

Other lines of evidence had already hinted at plant-eating pterosaurs. Skull leverage, bite-force estimates, and crest-balanced heads all point to strong bites and precise handling of bulky food.

Herbivory also pairs well with the Jehol ecosystem, where plants and small seeds were abundant. Grit assisted stomachs would help turn those tough resources into energy.

Rare gut snapshots change more than a menu entry. They anchor debates in direct evidence, and they reveal how anatomy and behavior worked together.

Future pterosaur fossils may tell more

Plant silica from the Cretaceous is not fully cataloged. Building larger reference libraries will help tie fossil shapes to living plant groups with more confidence.

We still do not know how often plant feeding occurred across pterosaurs. Future finds may show seasonal shifts, mixed diets, or age-based changes.

Even one stomach can recalibrate a field. This one shows that at least some pterosaurs chewed in their own way, with stones and muscle doing the work.

The study is published in the journal Science Bulletin.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–