Massive crocodile cousin from 70 million years ago ate dinosaurs and anything else it wanted

About 70 million years ago, in what is now southern Argentina, a close relative of crocodiles named Kostensuchus atrox lived as an apex predator at the top of the food chain.

This animal was a monster, roughly the length of a compact car, and it likely ranked near the very top of the food chain in its environment.

Scientists recently found its fossil bones, giving us a clearer picture of what was hunting in Patagonia near the end of the age of dinosaurs.

Meet Kostensuchus atrox

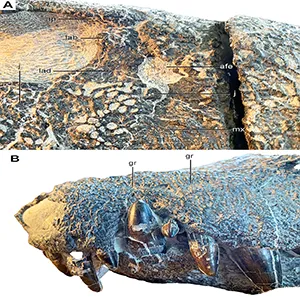

It measured about 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) long and may have weighed around 550 pounds (250 kilograms). It had a large skull, sharp, blade-like teeth designed for slicing meat, and strong limbs that suggest it could move powerfully on land.

The fossils were discovered in the Chorrillo Formation near El Calafate in Patagonia, a region known for preserving dinosaurs and other ancient reptiles.

Even though it was related to crocodiles, Kostensuchus wasn’t a modern crocodile. It belonged to a broader group called crocodyliforms.

That group of ancient reptiles share an ancestor with today’s crocodiles and alligators, but evolved in many different directions.

Some crocodyliforms were more land-based than the crocodiles we know now. The bones of this animal point to a stocky body, more upright limbs, and a skull built for crushing strength, suggesting it relied on power to take down prey.

Scientists named it Kostensuchus atrox after “Kosten,” the fierce Patagonian wind, “Souchos,” the Egyptian crocodile god, and “atrox” which means harsh. The name captures both place and power.

“Kostensuchus atrox gives us an incredible window into a vanished ecosystem,” said Fernando Novas of the Bernardino Rivadavia Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales.

Crocodile relative, not a dinosaur

Despite its size, K. atrox was not a dinosaur. It belonged to the peirosaurids, close relatives of modern crocodiles.

This is the first crocodyliform from the Chorrillo Formation and one of the best-preserved ever found. Its short, broad snout and strong jaw muscles reveal how it hunted. It was not a scavenger. It was a killer.

The teeth tell the story. Large, blade-like, and edged with fine serrations, they could slice flesh clean. Its jaws and muscles gave it a crushing bite.

Earlier peirosaurids were smaller, many weighing only tens of kilograms. Kostensuchus was different. Evolution pushed it toward hypercarnivory, specializing in large prey.

Sharing the top

In its world, only the massive megaraptorid Maip was larger. Together, they ruled the Chorrillo ecosystem. Farther north, predator groups looked different.

Abelisaurid dinosaurs dominated there, but southern Patagonia had a split rule: theropods and crocodile relatives side by side. This mix highlights how predator guilds varied even within the same continent.

The study compares Kostensuchus with baurusuchids, another predator lineage. Both groups evolved slicing teeth and powerful skulls. But they didn’t look the same.

Baurusuchids had long, narrow heads. Kostensuchus had a wide, short snout. Its forelimbs were also stronger, with signs of flexibility in the humerus. That difference may point to different ways of bringing prey down.

Anatomy of Kostensuchus atrox

Other bones offer more clues. Its shoulder girdle and pelvis suggest a posture not fully upright. It may have walked with limbs spread slightly wider, hinting at a lifestyle both on land and in water. Unlike modern crocodiles, it wasn’t limited to ambush in rivers.

It may have chased prey across floodplains too. Strong forelimbs support this idea. They could have pinned prey while the jaws delivered fatal bites.

The skull shows clear adaptations for muscle attachment. Deep pits and ridges allowed large muscles to anchor, boosting bite force.

The lower jaw bones were robust, and resisted stress from struggling prey and powerful thrashing movements.

Serrated teeth reveal repeated replacement, showing that it stayed well-armed throughout its life. These constant replacements meant damaged teeth never left the predator defenseless.

Together, these features confirm a predator that was suited for active hunting, not passive feeding, and was fully adapted to dominate its environment.

Dinosaurs and Kostensuchus atrox

Kostensuchus lived at the edge of extinction. It thrived in southern Patagonia’s warm, humid landscapes before the great asteroid ended the Cretaceous.

Its discovery proves that crocodile relatives were not background hunters. They were apex predators that, alongside dinosaurs, shaped ecosystems.

The find expands our view of crocodyliform evolution. It shows how these reptiles adapted to fill predator roles that were often thought exclusive to dinosaurs.

It also reveals differences between ecosystems in South America, where predator communities could change drastically over distance.

Without fossils like this, we might still think crocodile relatives were secondary players. Instead, Kostensuchus atrox reminds us that they were central to the story of life at the end of the age of dinosaurs.

The study is published in the journal PLOS One.

Featured image credit: Gabriel Diaz Yanten, CC-BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–