Earth has become a planet where the air is always thirsty, and that's quickly drying out the land

People usually link drought to one thing: not enough rain. Dry soil, low rivers, and crop losses all seem to point straight to the sky. In a warming climate, that simple picture leaves out an important part of the story.

As temperatures rise, the air develops an “extra thirst” for water from soil, rivers, lakes, and plants.

A recent global study asks how much that extra atmospheric thirst is pushing modern droughts, compared with changes in rainfall alone.

This research was led by Dr. Solomon H. Gebrechorkos, a climate change attribution expert at Oxford University’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, reveals that this growing “thirst” has intensified droughts worldwide by about 40%.

Atmospheric evaporative demand

Scientists call this thirst atmospheric evaporative demand, or AED, describing how strongly the air tries to evaporate water from land and vegetation.

Hotter air, more sunshine, lower humidity, and stronger winds all increase AED, so the atmosphere pulls harder on surface water.

Even if rainfall does not drop, higher AED can still dry out the land because more water leaves the surface.

For decades, many drought studies have focused mainly on rainfall, so this work set out to untangle how much of the current trend in drought comes from changes in rain and how much comes from changes in AED in a warming world.

Tracking AED and drought

The research team needed long and reliable records. They combined high‑quality global rainfall data with detailed information about weather and radiation at the surface.

From these inputs, they built several versions of a drought dataset for land between 50° south and 50° north, going back to 1901 and with especially detailed coverage from 1981 onward.

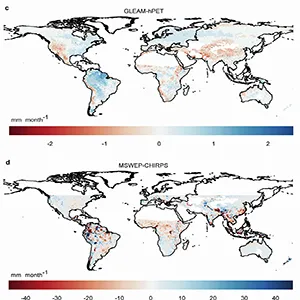

To reduce bias from any one source, they created four separate drought reconstructions using different combinations of rainfall and AED, then averaged them into one “ensemble” view.

To describe drought, they used the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index, or SPEI. This index compares water coming in as precipitation with water leaving through evaporation and plant transpiration, which AED controls.

The team focused on a six‑month version of SPEI that captures droughts developing over seasons.

They defined drought episodes when the index fell below a threshold and tracked how often those episodes occurred, how large the water deficit became, how much area they covered, and how these features changed over time.

Recent drought and AED trends

When the scientists examined the period from 1981 to 2022, they found that land, on average, moved toward drier conditions as the six‑month SPEI trended downward.

Earlier in the record, especially from about the 1950s to around 1980, many places leaned a bit wetter on average, which makes the more recent move toward dryness look like a systematic push rather than random ups and downs.

Over the study period, the fraction of land experiencing drought in any given month increased.

The recent past stood out even more. During the five‑year span from 2018 to 2022, the average fraction of land in drought jumped compared with previous decades.

In 2022, roughly a third of global land fell into moderate to extreme drought conditions in this dataset, making it the worst year in the record they analyzed. Europe in particular saw very widespread and intense drought as low rainfall combined with very high AED.

Regional drought and AED patterns

The planet does not respond the same way everywhere. Strong drying trends appeared in Europe, large parts of Africa, western North America, and certain parts of South America.

In these regions, SPEI showed consistent declines, meaning their drought risk has risen as the atmosphere has demanded more water.

Other regions told a different story. South and Southeast Asia and parts of eastern North America showed trends toward wetter conditions, where increased rainfall has more than balanced growing AED.

The character of droughts also changed. In southern South America, parts of Africa, southern Europe, and the western United States, both the frequency and the overall strength of drought episodes grew.

On a global scale, the typical duration of individual droughts did not show a clear trend, but the number and severity of events increased in many places.

Rain and atmospheric “extra thirst”

A key step in the study was a “data experiment” designed to separate the roles of rainfall and AED. In one scenario, rainfall varied over time exactly as observed, but AED stayed fixed at a long‑term average pattern.

In another, AED changed over time as in the real world, while rainfall stayed locked to its climatological values. The team compared these two artificial worlds with the real one, where both rainfall and AED change together.

When rainfall alone changed and AED stayed fixed, some regions still moved toward drought, but the global‑scale drying looked weaker and some areas even appeared slightly wetter.

When AED alone changed and rainfall stayed fixed, the drying trend became much stronger and more widespread. The comparison showed that rising AED by itself can drive substantial increases in drought conditions even without large drops in rainfall.

Since the early 1980s, changes in rainfall have explained a bit more than half of the global trend toward increased drought, while changes in AED account for a large minority.

In the world’s drylands, where water is already limited, the contribution from AED can reach a dominant share of the trend.

Physics of drought and AED

The physical picture follows the basic laws of thermodynamics. Greenhouse gases warm the air. Warmer air can hold more water vapor, so it “wants” to evaporate more water from the surface.

If rainfall is scarce, soils are already dry, or vegetation is stressed, the land cannot supply enough water to meet that demand. The shortfall shows up as a growing water deficit, and indices like SPEI record that imbalance between supply and demand.

Dry soils add another layer. When soil moisture is low, less energy goes into evaporation and more goes into heating the ground and the air.

That extra heating raises temperature and keeps AED high, creating feedback loops that lock in strong atmospheric demand.

‘This work shows that including AED in drought monitoring, rather than relying on precipitation alone, is essential for better managing risks to agriculture, water resources, energy, and public health,” explained Dr. Gebrechorkos.

“Given projected climate changes, especially rising temperatures, the impact of AED is expected to intensify.”

Lessons from drought and AED

In the future, drought risk will depend not only on how much it rains but also on how thirsty the air has become. Watching rainfall alone misses this growing pull from the atmosphere on land and water.

“We need to act now by developing targeted socio-economic and environmental adaptation strategies and improved early warning and risk management systems. Many affected areas are already struggling to cope with severe drought,” Dr. Gebrechorkos concluded.

Efforts to limit global warming, manage water more wisely, and develop crops and practices that can handle higher evaporative demand will strongly influence how well societies cope with the dry years ahead.

The full study was published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–