Invisible barrier discovered in the ocean that jellyfish won’t cross

Life in the deep ocean often sorts into hidden zones shaped by temperature, salt, and moving water. Many animals, like Botrynema jellyfish, stay within a narrow band of conditions, almost like having a stable homeland.

When a marine species turns up far outside that usual zone, it raises questions about both the animal and the ocean itself.

New research by marine scientists at The University of Western Australia (UWA) suggests that the way a deep-sea jellyfish of the Botrynema genus is distributed across the ocean may reveal a previously unknown biogeographic barrier in the North Atlantic.

In this case, the team found a Botrynema jellyfish, one that normally lives in icy Arctic waters, swimming far south of its homeland in dark, subtropical waters near Florida.

They used this discovery to rethink how this jellyfish is classified and how hidden “barriers” in the ocean shape where it can live.

Botrynema jellyfish are drifters

Most jellyfish switch between two main life stages: a floating, bell-shaped medusa, and an attached stage that clings to rocks or other surfaces.

The group in this study, called Trachymedusae, skips that second step. These jellyfish spend their entire lives as drifting medusae; they do not have the typical attached “polyp” stage that many other jellyfish have.

Within this group, the team focused on jellyfish in the the genus Botrynema, especially a subspecies called Botrynema brucei ellinorae.

For about a century, researchers thought Botrynema brucei was a widespread species found in both polar regions and in deep waters of many oceans, with Botrynema ellinorae as a northern jellyfish subspecies.

Over time, they noticed two body types, or morphotypes: one with a small bump on top of the bell, called an apical knob, and one with a smooth top and no knob.

Early work treated knobbed and knobless animals as different species, but later observations in Arctic and subarctic waters showed both shapes within the same jellyfish subspecies, Botrynema brucei ellinorae.

Tracking Botrynema on the map

The study set out to answer three connected questions: How is Botrynema actually distributed across the globe? How do the two body shapes relate to one another genetically? And how did a supposedly Arctic subspecies end up in deep subtropical water near Florida?

To tackle this, the researchers used physical features, DNA sequencing, maps of where specimens had been found, and more than 100 years of published records.

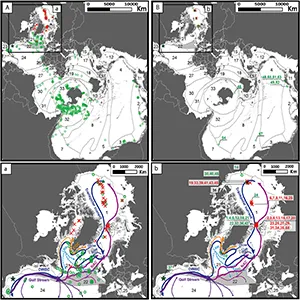

They also pulled in data from global biodiversity databases and removed clearly incorrect entries before plotting reliable records on a global map of midwater regions to see which zones Botrynema occupies.

Jellyfish catches in northern seas

Historical clues helped, but the team also needed fresh material. A research program in Norwegian Arctic waters captured dozens of Botrynema brucei ellinorae jellyfish using plankton nets.

Scientists photographed each jellyfish to document whether it had a knob or not, then preserved the animals for genetic analysis. These northern specimens formed a modern, well-documented set for comparison.

Because the animals came from a single region and depth range, this gave the researchers a clear picture of how the knobbed and knobless morphs look in life and how common each one is in Arctic and nearby subarctic waters.

Pale-pink drifter offshore

During a deep-sea research cruise in the western North Atlantic, a remotely operated vehicle explored the seafloor northeast of Florida at around 3,280 feet depth and filmed a jellyfish drifting in the darkness.

From the video, and by collecting the animal itself, researchers saw that it belonged to Botrynema. It had the characteristic apical knob on top of the bell, along with shield-shaped gonads that had a pale pink tint.

That single jellyfish became the key test case for whether the Arctic subspecies truly appeared so far south.

Because the team had both footage and a physical specimen, they could connect its look and behavior in the water with fine-scale measurements and genetic work in the lab.

What the genes showed

Back in the lab, the team extracted DNA from that deep Atlantic jellyfish and from the Arctic and subarctic samples. The result surprised them.

The new jellyfish’s DNA clustered inside the Botrynema brucei ellinorae jellyfish group and differed only slightly from the most common Arctic sequence.

This tells us that the southern animal is not a separate warm-water species. Genetically, it is essentially an Arctic subspecies individual that somehow ended up in deep subtropical water.

Knobs, currents, hidden borders

When the scientists looked at global distribution, a clear pattern appeared.

Knobbed Botrynema individuals occur in many oceans and across a wide span of latitudes, including temperate and subtropical regions.

The knobless morph, however, appears restricted to the Arctic Ocean and nearby subarctic parts of the North Atlantic, especially a narrow region called the North Atlantic Drift.

There are no solid records of knobless Botrynema jellyfish south of that zone in either major ocean, suggesting that it has a much more limited range than the knobbed form.

That raised a new question: if the subspecies is Arctic, how did it reach Florida, and why only in the knobbed form? The answer likely lies in deep-sea currents.

In the North Atlantic, cold, dense water sinks near Greenland and then flows southward as part of the ocean conveyor belt, including a branch called the Deep Western Boundary Current.

The authors argue that Botrynema brucei ellinorae jellyfish can drift within this deep current, traveling south without changing depth.

This water mass creates a route that connects Arctic deep-sea communities to lower-latitude basins, and the southern specimen probably traveled this way by drifting rather than by active swimming.

Soft barrier for morph jellyfish

At the same time, the study suggests there is a kind of “soft barrier” in the North Atlantic Drift region: not a wall or landmass, but a transition zone where water temperature, chemistry, prey, and predators shift.

North of this zone, both knobbed and knobless morphs of B. brucei ellinorae coexist. South of it, only the knobbed version appears.

The researchers propose that the knob might give a small advantage in those southern, somewhat warmer midwater zones where predators are more common, perhaps by changing how the jellyfish moves or how easy it is for predators to grab it.

“It could keep specimens without a knob confined to the north while allowing the free transit of specimens with a knob further south, with the knob possibly giving a selective advantage against predators outside the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions,” explained lead author Dr. Javier Montenegro.

Ocean barriers and Botrynema jellyfish

In the end, this jellyfish story is really about an invisible boundary drawn by the ocean itself.

Even though deep currents can quietly carry an Arctic jellyfish thousands of kilometers south, the “soft barrier” in the North Atlantic Drift helps decide which version of that jellyfish can actually make a living there.

North of that zone, both knobbed and knobless forms do fine, but south of it, only the knobbed morph seems able to handle the slightly warmer, more predator-filled midwaters.

By tracing one pale-pink drifter and comparing its genes to Arctic relatives, the study shows how hidden changes in water temperature, chemistry, and food webs can shape where life can and cannot thrive.

The full study was published in the journal Deep Sea Research.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–