Killer sea sponge, unlike anything seen to date, traps and devours live animals

Far beneath Antarctic waters, scientists have found a killer sea sponge with a near perfect ball shape that grabs and eats passing animals. It is the star of dozens of newly confirmed deep sea species from a remote part of the Southern Ocean.

A team from The Nippon Foundation’s Nekton Ocean Census worked with Schmidt Ocean Institute’s ship Falkor to reach this hidden region in 2025. They sent down a robot submarine to explore the seafloor and bring back animals for study.

Ecosystems hidden under ice

Early in 2025, an iceberg called A-84 broke away from the George VI Ice Shelf and uncovered seafloor that had been hidden under ice.

This new opening in the Bellingshausen Sea gave researchers their first direct look at a deep polar habitat that sunlight never reaches.

The work was led by Michelle Taylor, head of science at Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census and lecturer at the University of Essex.

Her research focuses on deep sea corals and how polar ecosystems respond to environmental change.

To reach the newly exposed seabed safely, the team sent down a remotely operated vehicle, a tethered robot submarine that carries lights and cameras.

Guided from the deck of the ship, this robot moved slowly over the bottom taking samples and recording detailed video.

They saw hydrothermal vents, hot springs on the seafloor that release mineral rich fluids. They also filmed bright coral gardens and the first confirmed footage of a juvenile colossal squid.

Death ball sponge’s hunting tricks

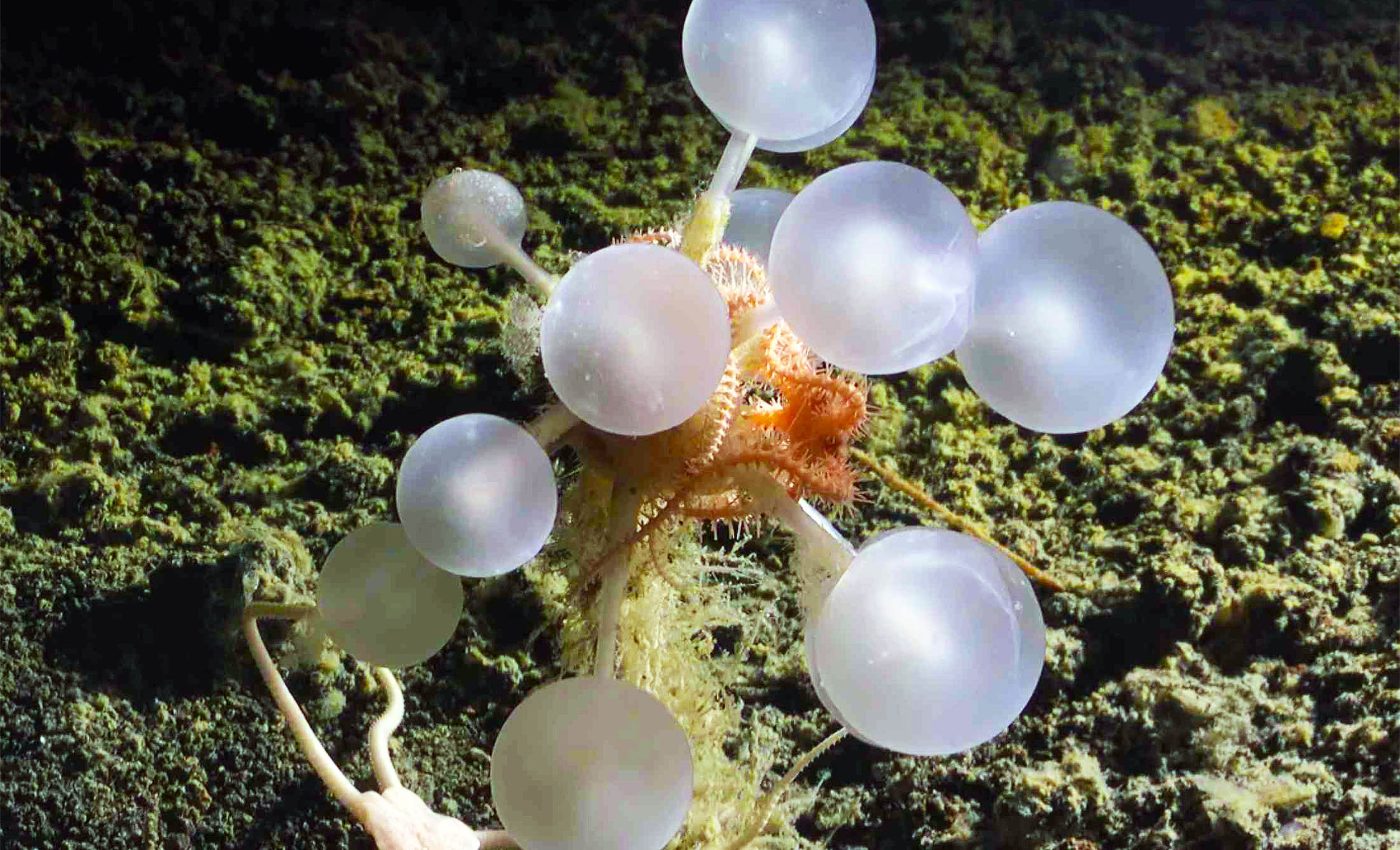

Among the new species, the most unsettling may be a carnivorous sea sponge that feeds by trapping and digesting animals.

This species has a nearly spherical body covered in tiny hooked structures, so small crustaceans that brush against it cannot escape.

It belongs to Cladorhizidae, a family of deep sea sponges that hunt rather than filter feed. In this group, thin filaments or small spheres form sticky surfaces that hold prey.

Carnivorous cladorhizid sponges occur in several oceans and are especially common at great depths where food in the water is scarce.

Studies suggest that this feeding style helps them survive where ordinary filter feeding would not supply enough energy.

Work in the Weddell Sea has recorded at least 27 carnivorous sponges in the Southern Ocean, more than half of them endemic.

The new death ball sponge adds one more specialist to that hidden collection and hints that many relatives still wait to be described.

Strange worms that feed on bones

Another standout resident of this seafloor is Osedax, a bone eating worm that lives on sunken bones.

These so-called zombie worms strip fats from the bones of whales and other large animals that die and sink into cold water.

Females lack a mouth and gut, instead relying on symbiotic bacteria, microbes that live inside their tissues and help release nutrients from the bone.

Studies of their breathing show that this partnership lets them thrive inside bones with little oxygen and many other reactive chemicals.

Since their first description from a whale skeleton off California in 2004, Osedax species have been found on many bones, including cow and fish bones.

That flexibility helps explain why zombie worms appear at whale falls worldwide and likely play a major role in recycling vertebrate remains on the seafloor.

In the Southern Ocean survey, the worms were seen on seal bones scattered near volcanic islands, quietly tunneling through the remains.

Their presence beside the death ball sponge shows how many different feeding strategies can share the same small patch of seafloor.

Life on volcanic and vented seafloor

Around the hydrothermal vents near the South Sandwich Islands, animals live in a chemical hotspot instead of a sunlit food web.

These communities rely on chemosynthetic microbes, organisms that get energy from chemical reactions rather than from light.

Previous expeditions to vents on the East Scotia Ridge showed that Southern Ocean vent fields host unusual communities compared with those at lower latitudes.

At these sites, crabs, barnacles, snails, and more crowd around vent openings supported by bacteria that use chemicals in the hot fluids.

In these surveys, scientists documented armored iridescent scale worms, unfamiliar sea stars, and crustaceans including isopods and amphipods adapted to volcanic slopes.

They also found snails and clams near vent fluids, hinting that some species live close to chemical sources while others keep a safer distance.

The team even visited parts of the South Sandwich Trench, a hadal zone, the deepest band of ocean trenches below about 20,000 feet.

At those depths, pressure is crushing, water stays near freezing, and yet life still forms communities on rocky outcrops and patchy sediments.

Southern Ocean is mostly unmapped

Despite decades of work, scientists know less about seafloor life in the Southern Ocean than about continental shelves closer to major research centers.

Seafloor surveys in Antarctica have revealed high biodiversity, many different species living together, yet large areas remain barely sampled.

“To date, we have only assessed under 30% of the samples collected from this expedition,” said Taylor. The Southern Ocean remains profoundly under-sampled.

Working in this region means long transit times, harsh storms, and a narrow weather window, so only a few research ships visit each year.

When they do, there is only enough time to sample a small number of sites, leaving huge stretches of seafloor unvisited.

Because of that, many polar habitats are effectively invisible in conservation plans, which often rely on existing records of species.

Each confirmed species becomes a data point that helps reveal where communities live and how they might respond to warming or fishing pressure.

From seabed to database

In the past, samples from deep sea cruises could sit in jars for years before taxonomists, scientists who name and classify species, examined them.

Limited staff and funding meant that many collections never received a full check, even when they contained species that were new to science.

For this work, the team assembled experts in a species discovery workshop so they could process specimens on board instead of shipping them away.

When anatomy alone was not enough, they used DNA barcoding, a method that matches short genetic sequences to known lineages, to flag new animals.

“Accelerating species discovery is not a scientific luxury, it is essential for public good,” said Mitsuyuki Unno, Executive Director of The Nippon Foundation.

He sees faster discovery as a way to give scientists and policymakers basic knowledge while there is still time to protect fragile habitats.

“Each confirmed species is a building block for conservation, biodiversity studies, and untold future scientific endeavors,” said Dr. Taylor.

Those building blocks will support conservation efforts far beyond this one expedition.

Sea sponges and ocean mysteries

Polar seafloor ecosystems are feeling the effects of warming, shifting currents, and changes in sea ice, even though many have not yet been mapped.

Knowing which species live where helps scientists predict which communities might cope with shifting conditions and which might disappear.

At the same time, interest in mining, fishing, and bioprospecting, searching for useful compounds in organisms, is increasing faster than surveys of life.

Without data from places such as the South Sandwich Islands and Bellingshausen Sea, it is hard to judge potential damage new industries could cause.

The Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census aims to close that gap by combining ship time, robots, and workshops to turn samples into data.

The death ball sponge and its neighbors are examples of how that approach can reveal species that would otherwise remain hidden in the dark.

These strange creatures are not just curiosities but key observations about how life adapts to harsh conditions on Earth.

Each new deep sea species from the Southern Ocean adds detail and shows that parts of the ocean lie beyond maps.

Image Credit: The Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census/Schmidt Ocean Institute © 2025.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–