Massive landslide in Greenland caused nine days of global seismic activity

Melting glaciers in East Greenland set the stage for a catastrophic chain reaction in caused by a massive landslide. When an unstable mountain slope finally gave way and crashed into a fjord, it produced a 650-foot wave.

That landslide also generated a mysterious seismic hum that rippled around the world for nine days.

That hum – one pulse every 92 seconds – became a rare natural signal that helped scientists uncover how warming reshapes hazards in the Arctic.

Greenland landslide’s seismic hum

At first, the very long period seismic waves – vibrations that repeat over many tens of seconds – seemed like a minor glitch to some monitoring teams.

Instead of fading within minutes, the hum from the landslide persisted day after day, rising cleanly every 92 seconds on graphs from Alaska to Europe.

“When we set out on this scientific adventure, everybody was puzzled and no one had the faintest idea what caused this signal,” said study lead author Kristian Svennevig, a geologist at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS).

Teams combined global seismic records with satellite images of East Greenland and searched for any sudden change along the coast.

Dickson Fjord collapse

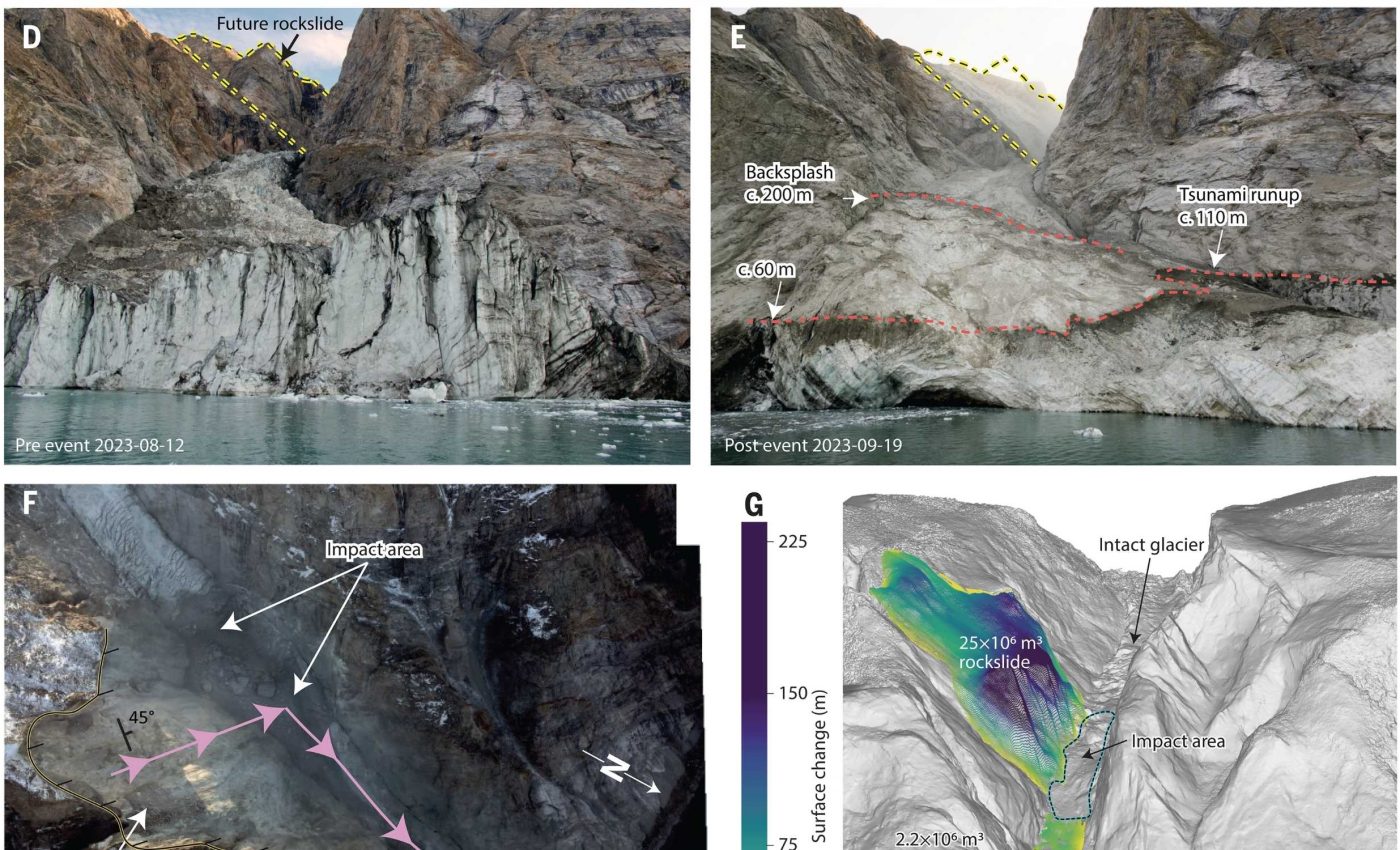

At the head of Dickson Fjord, an upper slope failed and dropped 25 million cubic yards of rock and ice into the inlet. That volume would fill roughly 10,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Where the landslide hit the water, a towering wave shot upward. It then sped down the narrow inlet, bouncing between steep rock walls.

Farther along the coast, waves reached the unmanned Nanok research station on Ella Island and rose about 13 feet, causing $200,000 in damage.

Computer models showed the waves in Dickson Fjord settling into a seiche – a standing wave that makes the water slowly rock.

That sloshing motion repeated at almost the same 92-second rhythm seen in the seismic data. That is why the signal sounded so regular.

Melting glaciers destabilize mountains

Decades before the landslide, the glacier below the failed slope had been thinning and retreating, removing the ice that once pressed against the rock.

A growing body of research, links such glacial melting with more frequent, large slope failures in steep mountain regions.

When the glacier shrank away from the foot of the mountain, it reduced de-buttressing – the support from heavy ice that props up steep slopes.

That left the upper slope more freer to expand and crack. Once gravity finally won, the collapse was fast and violent.

Scientists who study climate impacts warn that polar mountain regions are likely to see more similar events as warming continues.

Recent analysis shows bedrock landslides increasing in glacier-covered ranges as ice retreats and intense rainstorms grow more common.

Greenland has already seen what happens when a similar rock avalanche hits water near a community, such as the 2017 slide into Karrat Fjord. A detailed survey found the tsunami destroyed 11 homes in Nuugaatsiaq and killed four people.

Greenland landslide’s strange hum

Using simulated motion of the water and seismograms, the team showed that a push and pull from the seiche best explained the hum.

Researchers calculated the water motion pushed horizontally with about 500 billion newtons of force on the crust.

Long after the water calmed, the discovery changed how scientists think about what seismic networks can catch in remote, icy places.

“Climate change is shifting what is typical on Earth, and it can set unusual events into motion,” said study co-author Alice Gabriel, a geophysicist.

Other researchers have highlighted the event as an example of how a seiche can send persistent signals far beyond the basin where it forms.

Experts say rare signals may uncover how ice loss, ocean basins, and slow-moving disasters are connected.

Satellites confirm the massive landslide

Even before scientists agreed on the source of the shaking, Earth-observing satellites captured the disturbed water surface and changes along the fjord walls.

Space-based instruments helped confirm the height of the wave and the extent of the landslide, giving a clearer view of the disaster.

Those instruments track glacier retreat, ground motion, and sea level in polar inlets, making it easier to spot slopes that might be approaching failure.

“It was exciting to be working on such a puzzling problem with an interdisciplinary and international team of scientists,” said study co-author Robert Anthony, a USGS geophysicist.

The study is published in Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–