Meet 'Megachile lucifer,' a devil-horned bee species from Australia

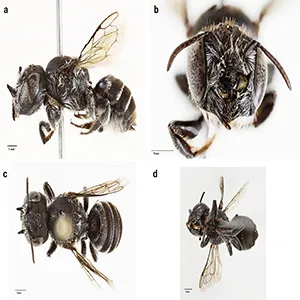

Scientists have identified a new native bee from Western Australia with tiny, devil-like horns on its face. Each horn is about 0.04 inches (1 millimeter) long, unmistakable, and points slightly upward.

The insect, named Megachile lucifer, was found in the Bremer Range region during a survey of a critically endangered wildflower.

The discovery comes from a team of researchers led by Dr. Kit Prendergast, an adjunct research fellow at Curtin University (CU), working in the Goldfields of Western Australia.

A bee with a strange face

The horns sit on the clypeus – the plate on a bee’s face above the mouth and between the antennae. In this species, the clypeus is deeply set and has a raised midline.

The formal species paper reports paired facial horns and measures their length at about 0.04 inches (1 millimeter).

The authors also show that the male Megachile lucifer’s last abdominal plate has two shallow lobes – a trait that helps separate it from lookalikes.

“I was super excited to find it,” said Dr. Prendergast. She added that the Latin name lucifer means light bringer and that the horns inspired the choice.

Megachile lucifer‘s horns

Only Megachile lucifer females bear the horns, which is unusual because showy structures often occur in males among many animals. Here, the sex-specific trait hints at a practical role, and not courtship.

One idea is that the horns help females push into tight flowers or nudge away rivals when resources run short. Another is that they help brace the face while packing material at a nest entrance with the jaws.

Similar, female-only structures appear in a few other bee lineages, where they help dig, pack, or defend. That pattern strengthens the idea that these tiny horns earn their keep during work rather than display.

Future observations at flowers and at nests should reveal when the horns of Megachile lucifer touch plant tissue or nest walls. Simple field videos could answer that question faster than genetic analyses or models.

Megachile lucifer is unique

To test the identity of Megachile lucifer, the team used DNA barcoding – a lab method that identifies species from a short gene sequence. The barcode did not match any existing entry and it showed a clear gap from its nearest relative.

They also checked museum collections and regional surveys for matching specimens. Nothing turned up, which suggests that this is a truly distinct species.

The shape of the face, the pattern of body hairs, and the details of the wing veins all lined up with one lineage within the leafcutter bee genus. Taxonomists call that lineage a subgenus – a rank below genus – and this species falls within Hackeriapis.

The team described fine points with calibrated photographs and measurements under a stereomicroscope. Those measurements are what will allow future researchers to recognize the species anywhere it appears.

Hidden in a brief bloom

All confirmed records come from a small part of the Goldfields around the Bremer Range. Finding so few individuals suggests a narrow footprint and a short flight period in early summer.

Botanists catalog Eucalyptus livida in EUCLID as a common small tree in the central and southern Goldfields, which matches where the bee turned up. Surveys that missed the species in other months point to a restricted window that is tied to that bloom.

The bee also visited the rare Marianthus aquilonaris, a wiry shrub with pale flowers that grows on iron-rich soils. That contact does not prove exclusive dependence, but it flags a possible link worth testing.

Such tight timing means a species can be invisible if you miss a few warm weeks. It also means fieldwork needs to follow the flowers, not the calendar.

Tiny bee, major role

Marianthus aquilonaris is listed as critically endangered in the Western Australian database, FloraBase, and it occupies only a few sites. If a local pollinator helps it set seed, losing that insect could hurt the plant.

Australia hosts about 2,000 native bee species, according to CSIRO, yet many remain undescribed and unmonitored. That gap makes it easy to overlook species that quietly prop up rare plants.

Mining, altered fire, and a heating climate all threaten the same landscapes that shelter specialist bees. When habitats change, flight seasons and flower timing can drift apart, and bees that miss their bloom lose both food and nest clues.

Pollination is a network, and rare plants often rely on only a few insect visitors. Remove one piece, and you may remove the chance to set seed that season.

Tracking Megachile lucifer

Practical steps start with surveys during the same weeks in November, when the bee was first seen. Researchers also suggest searching for nests in small, beetle-bored holes in fallen wood and in old trunks.

Local projects can protect trees with suitable holes and keep buffers around flowering shrubs and mallee patches. Even small choices – like the placement of roads and drill pads – can determine whether these microhabitats persist.

Public participation helps too, from reporting sightings to planting local shrubs that feed native bees through the dry months. Naming a species unlocks that attention because it anchors field data and conservation plans to something specific.

Community science platforms can log photographs with time and place, helping researchers spot patterns at scale. Good records can guide professional surveys to the right valleys and weeks.

The study is published in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

Image credit: KS Prendergast and JW Campbell

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–