New species of metallic beetle has adapted to extreme cold

High on a cold Peruvian ridge, scientists found a new metallic beetle species, Konradus trescrucensis, that is about one third of an inch long – roughly the size of a fingernail.

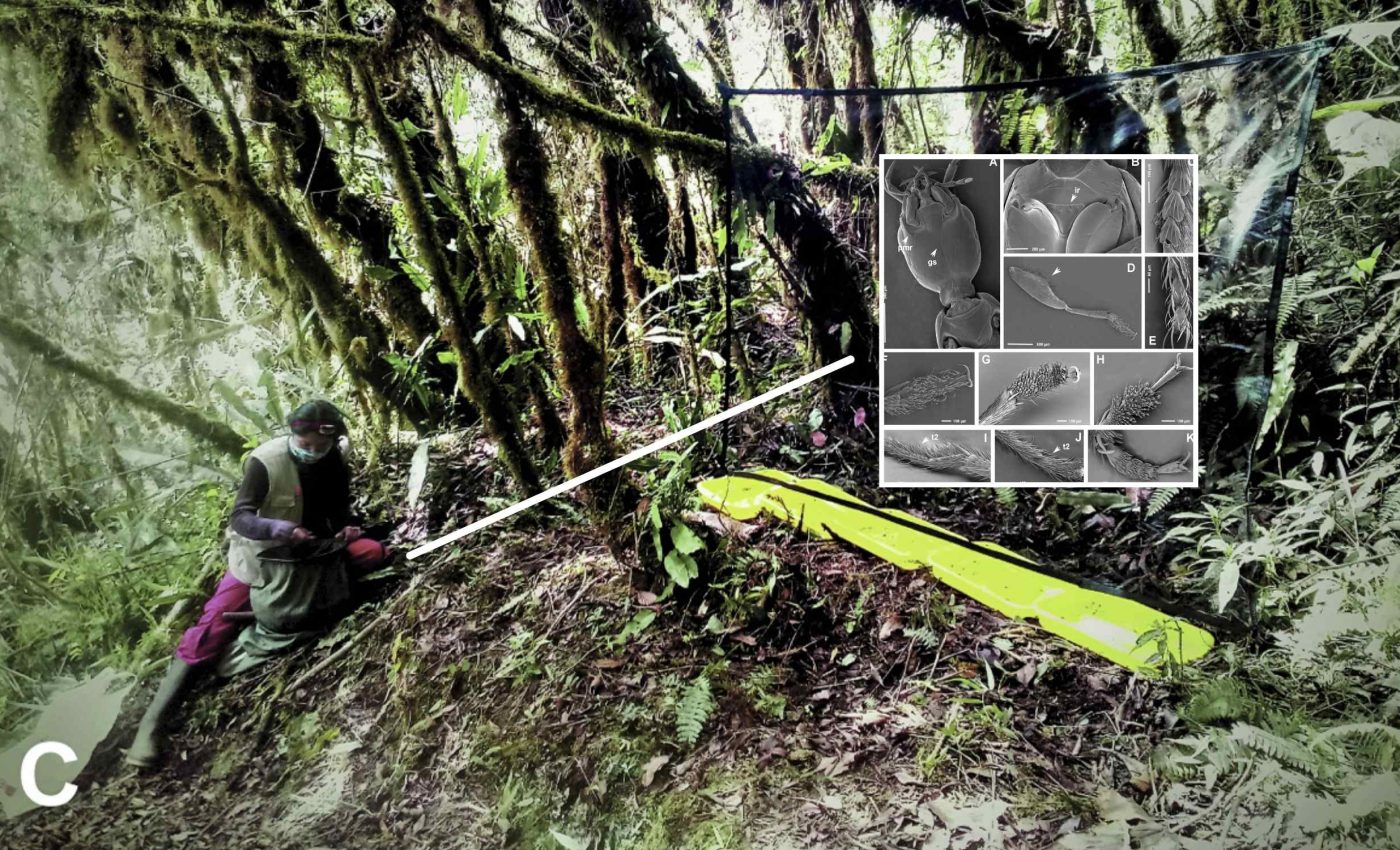

Konradus trescrucensis lives in a cloud forest, a mountain forest that stays cool and misty most of the year. The discovery is part of an international project that has named five new beetle species from the tropical Andes and reexamined museum specimens.

Four of the new species live on the high, wet slopes around Manú National Park, where thin air and cold nights are normal.

Konradus trescrucensis likes it cold

The work was led by an entomologist named Mariana Chani-Posse. Her research centers on how beetle species from South American mountains are related and how their bodies adapt to harsh environments.

Manú National park stretches from lowland rainforest to peaks more than 13,700 feet above sea level and holds an exceptional mix of wildlife.

Konradus trescrucensis comes from Tres Cruces, near the park’s upper entrance, where nights can feel more like late autumn than the tropics.

Scientists describe the tropical Andes as a biodiversity hotspot, a region with many unique species under strong human pressure.

Mountains that rise quickly from rainforest to cold peaks pack many climates into short distances, so neighboring slopes can host very different communities.

In the Manú region, moisture from the Amazon drifts up the Andes, cools, and turns into steady fog and near-daily rain.

Higher up, strong winds and thin air make life harder, yet mosses, orchids, birds, and beetles still manage to survive.

Metallic beetle built for altitude

In their study, the team describes Konradus trescrucensis as a slim metallic beetle only about 8.5 to 8.8 millimeters long.

It belongs to the rove beetles, a huge family of narrow, quick beetles that often hunt other small invertebrates.

Konradus trescrucensis has long, fine hairs on the undersides of its feet that form pads, helping it cling to wet leaves and rock.

The authors suggest these gripping structures are especially useful in steep cloud forests, where rain, moss, and flowing water make every surface slippery.

This project also describes three new species in a new genus called Yuracarus, which share a similar slender body and metallic sheen.

New Yuracarus species come from Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, and two of them live on slopes that surround Manú National Park.

Metallic bodies may help scatter light and blend with wet leaves, or they may just reflect how the outer shell develops.

Researchers still do not know exactly why this shine is so common in high Andean beetles, which makes these finds especially intriguing.

Rewriting beetle family trees

Biologists group related species into a genus, a category that gathers very similar organisms under a shared name.

Getting those groupings right matters because they tell us how traits evolved and how lineages spread across mountains, rivers, and continents.

To see where Konradus and Yuracarus fit, the team carefully scored dozens of body characters, from head shape to tiny structures in reproductive organs.

Computer programs then built evolutionary trees that consistently placed both genera in a tight Andean cluster, separate from similar looking beetles on other continents.

Two older species, once labeled under the catch-all name Philonthus, turned out to share key traits with the new Andean groups.

By moving them into Konradus and Yuracarus, the authors linked scattered records from Bolivia into a fuller picture of Andean beetle history.

Much of this work depends on careful morphology, the study of body form, using microscopes, photography, and even scanning electron instruments.

The team also mapped specimen locations across the beetles’ range, showing that they track bands of cold, wet forest along the Andes.

Biodiversity pressure

Large biodiversity dataset projects now track species records across the Tropical Andes, helping scientists see where conservation gaps remain.

Finds like Konradus trescrucensis plug real animals into those maps, turning abstract points into living populations in specific valleys and ridges.

The Tropical Andes region holds about one sixth of Earth’s plant species, and more than half are endemic, found only there.

Such concentration makes this mountain belt extremely sensitive to land clearing, mining, road building, and rapid climate change.

Manú and its surrounding buffer zone, an area with limited human use around a protected core, give wildlife space to move as conditions change.

“This advance reinforces the value of Manú as an epicenter of biodiversity and a natural laboratory for science,” said José Nieto Navarrete, the president of Sernanp.

Sernanp stands for the National Service of Natural Protected Areas by the State (Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado).

It functions as a Peruvian government agency responsible for conserving the country’s protected natural areas.

Rising temperatures push cold adapted species upslope, while expanding roads, farms, and mines squeeze habitats from below.

High elevation specialists like Konradus trescrucensis have very little room left to move, so detailed records become vital baselines for future surveys.

Lessons from Konradus trescrucensis

Rove beetles play key roles in nutrient cycling, as shown by field research on beetles that help break down animal carcasses in forests.

By consuming dead tissue and hunting other insects, they help recycle nutrients and keep many small pest populations in check.

In cold, wet Andean forests, beetles like Konradus and Yuracarus likely help clear dead plant material and small carcasses that would otherwise rot slowly.

Because they respond quickly to changes in temperature, moisture, and habitat structure, their presence or absence can signal deeper shifts in mountain ecosystems.

Every labeled specimen in a drawer, from a tiny beetle to a bird or orchid, records where and when an organism once lived.

Those records help scientists track lost ecosystem service, a helpful natural process such as pollination or decomposition, when species disappear from certain sites.

The fingernail sized metallic Konradus trescrucensis and its Andean relatives show that even in protected areas, much of life remains unnamed and poorly known.

Paying attention to these small, cold adapted beetles strengthens the case for conserving mountain forests and continuing field work in the tropical Andes.

The study is published in Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–