Solar device converts salt water into drinking water at record speed

A compact new solar device from the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) turns seawater into safe drinking water, without any external power. It produces roughly 0.084 gallons of freshwater per square foot each hour.

The core trick is simple to state and hard to achieve. The system keeps the sun heated surface clean while moving salt to the edges, so evaporation does not stall.

Fast solar salt water still

The device channels sunlight into heat using La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 – a black oxide that acts as a photothermal, converts light into heat and material. Heat forms right where water meets air, so energy is not wasted warming the whole tank.

The work was led by Sourav Chaule at UNIST. His research focuses on photothermal desalination and resource recovery.

In controlled tests, plain water evaporated at about 0.12 pounds per square foot per hour, and a bare glass fiber membrane reached about 0.21 pounds per square foot per hour. The prototype kept steady performance for two weeks in feeds with 20 percent salt.

Removing salt from the water

Water climbs through tiny channels in the membrane by capillary action, upward flow through small pores driven by surface tension.

The design connects the water supply at one end, so flow goes in one direction and salt naturally concentrates at the far edge.

That edge loading keeps the sunlit face clear, which boosts uptime and reliability. The team reports it delivered, maintaining strong antifouling capabilities in complex environments. .

Because salt crystallizes at the rim, it can be collected instead of returned to the source. The paper notes that the device enables Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) through effective salt collection.

Implications of La0.7Sr0.3MnO3

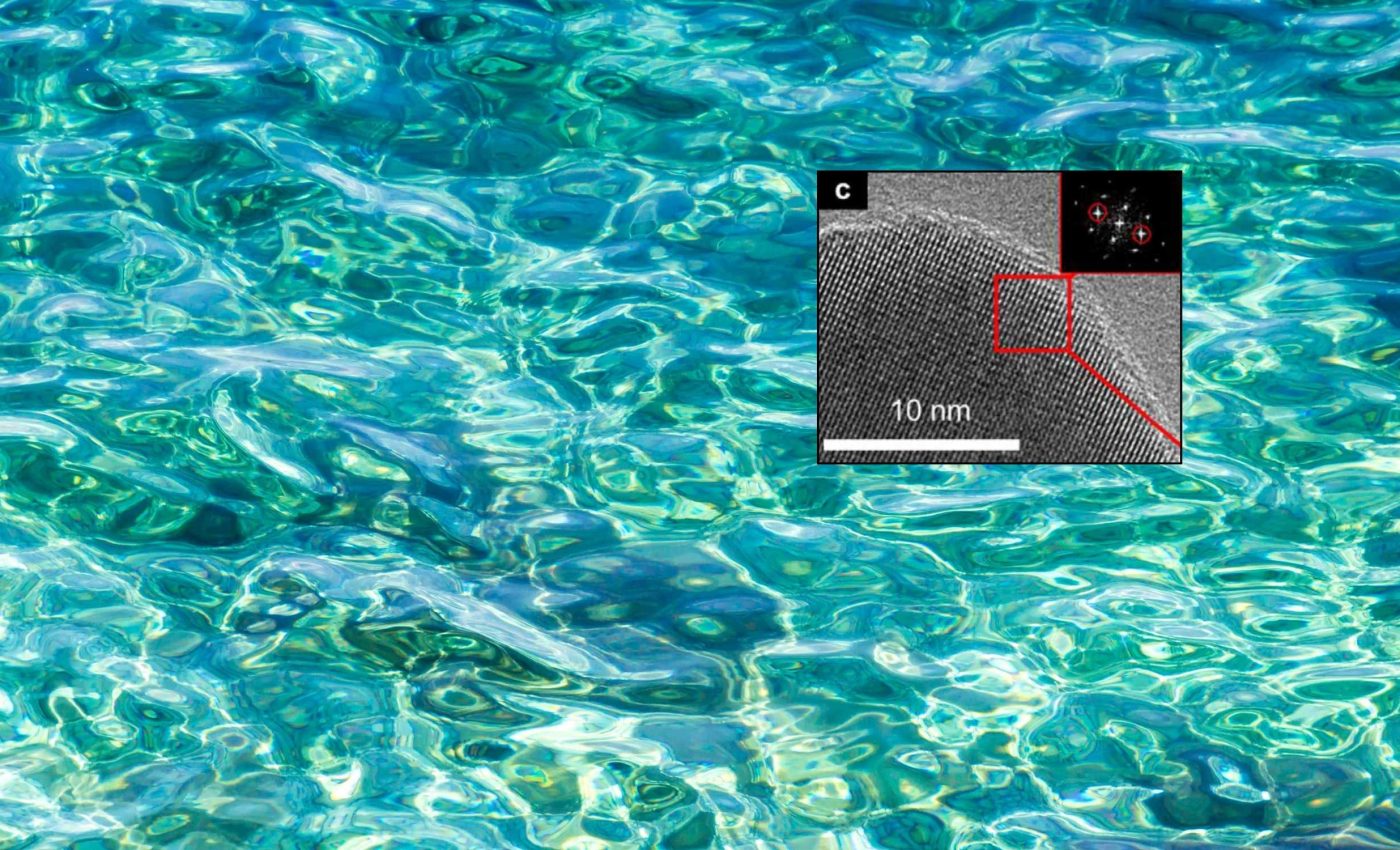

La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 is a perovskite – a crystal family whose composition can be tuned – that absorbs across most of the solar spectrum. Strontium substitution narrows the electronic gap, which helps the material drink in sunlight.

Inside the crystal, defect states favor non radiative recombination, electrons and holes meet and release heat instead of light, so absorbed energy turns into warmth. That warmth drives evaporation at the surface where it counts most.

Infrared imaging showed the top surface warming from about 82 degrees Fahrenheit to about 117 degrees Fahrenheit in one hour, while the bulk water stayed near ambient. Keeping heat where vapor forms helps explain the high output and low heat loss.

From lab to real world

The team screen-printed the material onto sturdy fiber membranes, then assembled several evaporators in a simple housing. That approach suggests manufacturing routes that do not depend on rare parts or tight tolerances.

Outdoors in winter conditions, the setup produced about 5.33 pounds of evaporation per square foot over six hours, and captured roughly 2.46 pounds per square foot as liquid water.

Those values came from four small modules running side by side without external power.

Tests with real seawater showed stable output and clean condensate. The authors explained that the condensed water was well below the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for safe drinking water.

Scaling the technology

A key challenge for any desalination system is bridging the gap between lab performance and daily use in real towns.

The modular nature of this device means units can be added or removed, which allows operators to match output to local water needs. These modular blocks also make repairs easier, since a single faulty unit can be swapped without interrupting the entire setup.

Field tests suggest that arrays of inverse L shaped evaporators can be organized into larger panels that run without skilled labor.

Communities with strong sunlight but limited energy access could place these panels near shorelines or brackish wells and expand capacity over time.

This approach could also help remote regions manage seasonal changes in demand by adding modules during dry months and storing extras when water is more plentiful.

Removing salt from seawater

According to a global report, one in four people still lack safely managed drinking water. Affordable devices that run on sunlight can expand options where pipes, pumps, and grids fall short.

Lab reports often cite AM 1.5 G, a standard sunlight spectrum used for testing, as the reference for one sun condition. That standard gives a common yardstick for comparing devices across labs.

This prototype points to practical upgrades, including better condensers to harvest more of the vapor it makes. Arrays of inverse L shaped evaporators could raise throughput while keeping maintenance low.

The study is published in Advanced Energy Materials.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–