Some frogs eat hornets and endure stings that would kill a mouse

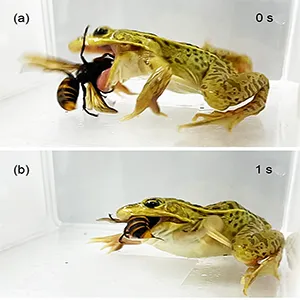

Researchers filmed a small pond frog in Japan as it swallowed live hornets and then sat there as if nothing happened. The core finding is simple: most frogs tested ate the hornets despite getting stung.

In controlled trials, the scientists offered 45 adult frogs three common hornet species as prey, and the frogs often ended the fight with a gulp.

How frogs eat hornets safely

The work was led by Shinji Sugiura, an ecologist at Kobe University in Japan. His research focuses on predator prey interactions and how generalist hunters deal with stinging insects.

Frogs attacked workers of three species, including the Asian giant hornet, and the hornets stung them on the face, eyes, tongue, and mouth. The animals still swallowed their prey and resumed normal behavior.

Across species, 93 percent of attacks on the Japanese yellow hornet ended in a meal, 87 percent for the yellow-vented hornet, and 79 percent for the Asian giant hornet.

Many strikes landed directly on the hornet’s body while the frog’s mouth took the stings.

“Although stomach-content studies had shown that pond frogs sometimes eat hornets, no experimental work had ever examined how this occurs,” said Sugiura.

Why hornet venom hurts

Hornet venom, a toxic mixture injected through a stinger, contains small amines, peptides, and enzymes that can rip cell membranes and upset the heart and blood, notes a recent review.

These ingredients explain the sharp local pain and the more serious systemic trouble that can follow multiple stings.

A recent laboratory report on venom toxicity calculated just how potent an Asian giant hornet can be.

One sting, when injected into a vein, can deliver enough venom to kill a 9.5 ounce (270 gram) mouse. That context makes the frog’s apparent resilience all the more striking.

Pain does not equal danger

Pain and danger are not locked together in the world of stinging insects. An exploratory analysis comparing many species found no consistent link between how much it hurts and how deadly the venom is.

Some insects pack a brutal sting that mostly screams “back off,” while others do quiet damage with less drama. That split helps explain how an animal might weather intense pain yet avoid lasting harm.

How frogs defend against hornets

Frogs show a mix of behavioral and internal responses when dealing with dangerous prey, and these responses might vary by species or even by age.

Some individuals could have stronger barriers in their skin or mouth that reduce how much venom enters the body during an attack.

Researchers are also considering whether these defenses have tradeoffs. A system that blocks toxins or pain might come with metabolic costs, which would shape how often these defenses appear in wild frog populations.

How frogs overcome hornet stings

The experiments hint that larger frogs did better, a pattern that suggests body size and internal chemistry both matter.

Those hints point to physiological, body-based defenses that tamp down pain or blunt toxin effects.

Mouth mechanics could help too. Frog saliva shows shear-thinning, a fluid property where viscosity drops when stirred, which lets a tongue spread gluey spit on impact and then release prey during swallowing. That trait could shorten the time a stinging insect has to fight back.

Different species have solved the pain problem in different ways. Nature offers other roadmaps for toxin tolerance.

Grasshopper mice, for instance, carry changes in a sodium channel, a protein that helps nerves fire. This response blocks bark scorpion toxins.

“While a mouse of similar size can die from a single sting, the frogs showed no noticeable harm, even after being stung repeatedly. This extraordinary level of resistance to powerful venom makes the discovery both unique and exciting,” said Sugiura.

How a frog handle hornet venom

Frogs may rely on internal systems that break down or block toxins before they can spread through the body.

Enzymes in their tissues could neutralize parts of the venom soon after exposure, which would limit both pain and damage.

There is also interest in how their nerves respond to painful stimuli. Some vertebrates reduce pain by changing how nerve channels transmit signals, and frogs might show a similar pattern that keeps stings from overwhelming their bodies.

What comes next

Two big questions follow. Do frogs make pain blocking or toxin neutralizing proteins, or are hornet venoms simply not tuned to amphibian targets?

Answers could steer research toward new pain biology and new ideas for anti-venom strategies. They could also clarify how often such predator defenses arise in vertebrates and whether they come with tradeoffs.

The study is published in the journal Ecosphere.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–