Stem cell transplant trial restores movement in stroke victims

Scientists in Zurich restored lost connections in mouse brains after stroke using human stem cell transplants. Animals regained movement that usually never returns, a sign that repair circuits can be rebuilt.

According to a report, globally, one in four people older than 25 will have a stroke in their lifetime. The University of Zurich team shows a path toward repairing the brain itself rather than only rescuing tissue in the first hours.

The work was led by Christian Tackenberg, Scientific Head of the Neurodegeneration Group at the University of Zurich. His research focuses on neural repair and human stem cell models.

Tackenberg noted that finding new ways to support brain repair after injury remains essential because current options cannot reverse the loss of neurons. He added that stroke care can limit further harm, but it still falls short of rebuilding the damaged circuitry.

Stem cell treatment after strokes

In mice, researchers transplanted human induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSC), adult cells reset to an embryo like state, derived neural progenitor cells one week after stroke and tracked recovery in the injured cortex. These IPSC were steered into neural progenitors for grafting.

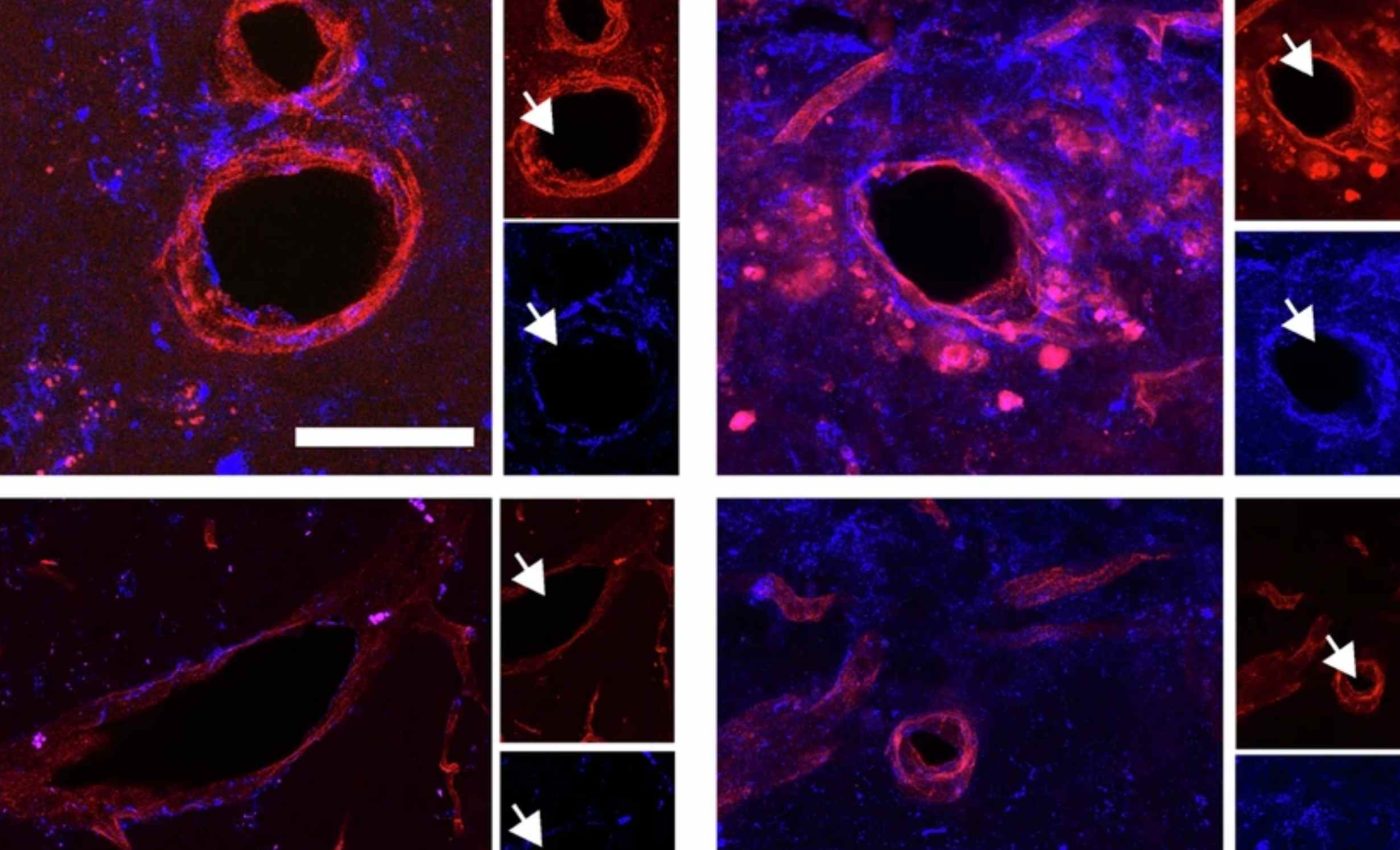

After transplant, the brain shifted toward healing signals, blood vessel growth increased, and inflammation calmed near the injury.

Motor function improved as animals relearned skilled steps across ladders and steady walking on a runway.

The team analyzed movement with a computer vision method that quantifies subtle joint and paw kinematics. This markerless pose estimation, video tracking that needs no reflective markers, catches tiny shifts that are easy to miss by eye.

How the new cells talk to the brain

Single cell profiling showed many grafted cells became GABAergic neurons, inhibitory nerve cells that help balance activity. Others adopted a glutamatergic identity, which excites circuits that move limbs and guide sensation.

Molecular mapping pointed to graft host communication through neurexin, neuregulin, neural cell adhesion molecule, and SLIT signaling.

These cues support axon guidance, signals that steer growing nerve fibers, and help rebuild synapses across damaged tissue.

The researchers reported that the transplanted stem cells remained alive for the full five-week study period and that most developed into neurons capable of forming connections with the host brain.

They observed neurites extending into the opposite hemisphere, which matched the improvements seen in movement tests.

Implications for future treatments

Researchers view these findings as an early sign that cell therapy might one day support stroke recovery in people. The approach aims to rebuild damaged networks rather than only limit injury in the first hours.

Teams are also working on delivery methods that place cells into the brain with less invasive procedures. These efforts focus on improving how cells settle into injured tissue while keeping the process as safe as possible.

Scientists are studying ways to prevent uncontrolled growth while still allowing transplanted cells to integrate into damaged circuits. That work could make long term use of stem cell based therapies more practical.

If these challenges can be solved, future treatments may combine cell therapy with rehabilitation to help patients relearn lost skills.

Long-term studies will be needed to confirm that these grafts remain stable and effective across different types of injuries.

Why timing and safety matter

Transplanting at seven days seemed to hit a sweet spot, after the most toxic early events settle yet while plasticity is still high.

That therapeutic window, the period when a treatment works best, could also give clinicians time to prepare personalized cells.

Genetic safety switches like inducible caspase 9 can remove transplanted cells if needed. An inducible system, a control triggered by a specific drug, offers a way to curb growth if grafted cells misbehave.

A recent phase I II trial in Japan found that iPSC derived dopaminergic progenitors survived, produced dopamine, and showed no tumors in Parkinson’s patients.

These dopaminergic progenitors, immature cells that make dopamine, give a real world sign that iPSC based neural grafts can be delivered safely in people.

Stroke is not Parkinson’s, and the injured cortex poses different challenges than the midbrain. Still, the concept of replacing lost cells while nudging repair programs offers a common translation, moving a method from lab to clinic, that could benefit multiple disorders.

Stem cells, strokes, and the future

Next steps include testing less invasive routes and confirming that human grafts wire into human circuits with the same precision.

Researchers will also refine immunomodulation, treatments that tune the body’s immune response, so grafts survive without long term immune suppression.

For patients and families, the take home is simple yet hopeful. If future trials can repeat these effects safely, cell therapy could one day help restore independence after a stroke, not only prevent the worst early damage.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–