Ancient stone toolkit reveals the lifestyle of Paleolithic hunters

The human story stretches back tens of thousands of years, and sometimes it resurfaces in the most unexpected ways. A road collapse in a quiet Czech village, a chance opening of forgotten cellars, or a fragment of stone pulled from the soil can reveal how our ancestors lived, worked, and survived.

Archaeology is never just about artifacts – it is about people. What they touched, carried, and shaped offers us a glimpse of their struggles, choices, and resilience.

Such a moment unfolded in the Pavlovské vrchy mountains of the Czech Republic, where archaeologists uncovered what may have been a hunter’s personal toolkit from 30,000 years ago.

Each piece, shaped and worn by human hands, links us to the ingenuity of those who came before us.

Ancient toolkit discovery

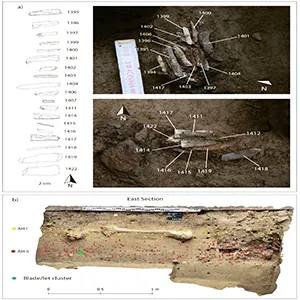

Archaeologists revealed 29 stone artifacts carefully positioned together. Blades and points dominated the collection, designed for hunting, skinning, butchering, and cutting wood.

The discovery was more than a collection of tools; it was evidence of daily routines and survival strategies.

“The 29 artifacts, which include blades and points meant for hunting, skinning, basic butchering and cutting wood, offer a rare glimpse into the daily lives of ancient hunters,” said Dominik Chlachula at the Czech Academy of Sciences in Brno.

This rare find highlighted the practical intelligence of early hunter-gatherers. The collection provides a unique record of how humans adapted to harsh Ice Age environments, balancing resource use with creativity.

Dig site with a bundle of stone tools

The story began in 2009, when a road collapsed in the Pavlovské vrchy mountains, exposing abandoned village cellars.

Archaeologists seized the chance to investigate. More than a decade later, in 2021, they discovered a deeper layer of the site known as Milovice IV.

Here, they uncovered charcoal dating to between 29,550 and 30,250 years ago. This ancient hearth provided a temporal anchor, situating the site firmly in the Upper Paleolithic period.

Among the remains were horse and reindeer bones, the hunted prey of Ice Age communities.

Resting near these bones, archaeologists encountered a bundle of stone tools, still aligned as though they had once been wrapped in a leather pouch, long since decayed.

Heavy tool use

Closer study revealed the intense use of these artifacts. “The tools showed signs of significant use,” noted Chlachula.

Blades were dulled from repeated scraping of hides, cutting of bones, and working of wood. Some even bore evidence of having been fixed into wooden handles.

Several pointed tools carried impact fractures, their surfaces recording the force of hunting encounters. One was likely used as the tip of a spear or arrow.

These signs transformed the collection from static objects into echoes of action. Each mark told of hunts pursued, hides cleaned, and shelters built.

Recycling in the ancient toolkit

Several artifacts had been reshaped from earlier tools. Chlachula suggests this may reflect either the scarcity of good stone or the hunter’s determination not to waste resources.

Recycling was not only practical but essential in a world where survival meant stretching every material to its limits.

This adaptive behavior also shows how ancient people valued efficiency. Tools could be renewed, reshaped, and reborn, carrying forward their usefulness until they were no longer functional.

Resources shared across vast areas

Material analysis deepened the mystery. About two-thirds of the toolkit had been crafted from glacial flint sourced at least 130 kilometers north of the site. Considering winding footpaths, the journey may have been even longer.

Most of the other tools came from western Slovakia, about 100 kilometers to the southeast.

“Further analyses revealed that about two-thirds of the tools had been crafted from glacial deposit flint stones found at least 130 kilometers northward – and significantly farther if using winding footpaths to reach them,” said Chlachula.

“Most of the others appeared to come from western Slovakia, about 100 kilometres south-east. Whether the owner acquired the stones directly from deposits or through a trade network remains unknown.”

These distances suggest long migrations, far-reaching hunting ranges, or the presence of early exchange networks that allowed communities to share resources across vast areas.

Toolkit stones from afar

Many pieces in the bundle were too worn or broken to be useful. Yet they remained with the collection.

“Many pieces were too worn or broken to be used as is, he explains. But it is possible the hunter kept them in the hope of recycling them – or even for their sentimental value,” explained Chlachula.

This possibility shifts the discussion from practicality to emotion. Humans often retain objects for reasons beyond their utility. A broken blade may have carried memory, pride, or significance tied to a hunt or a mentor.

These remnants show that even in the Ice Age, people may have attached feelings to their tools.

Indispensable tools for daily life

The ancient toolkit sat in a world of constant motion. The bones of horses and reindeer nearby hint at seasonal hunts, with groups tracking herds across cold plains.

Hides became clothing and shelter, bones and antlers were shaped into other instruments, and fires offered warmth against the bitter climate.

In such a setting, a toolkit was indispensable. Portable, versatile, and reliable, it was the key to food, clothing, and protection. It carried not only practicality but also the shared wisdom of a community passing knowledge across generations.

Survival toolkit of ancient hunters

This find reminds us that survival was never just about strength but about adaptability. Ancient hunters carried knowledge embedded in stone, shaped by journeys across hundreds of kilometers, exchanged through possible networks of trust and cooperation.

Even after thirty millennia, their choices speak to us: conserve resources, recycle what can be salvaged, and remember the human stories carried by objects.

A collapsed road gave back more than a collection of artifacts. It returned a narrative of resilience, intelligence, and humanity that still resonates.

The study is published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–