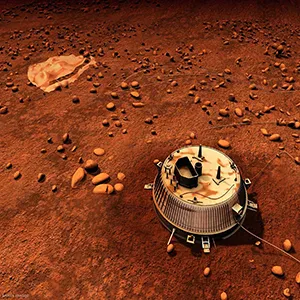

NASA captured this image on Titan 20 years ago, and it continues to perplex scientists today

On January 14, 2005, the European-built Huygens probe touched down on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. With that single landing, it became the first and only human-made object to land on the ground in the outer solar system.

Titan sits far from us, roughly 750 million miles (1.2 billion kilometers) away at typical distances, and it wears a thick, orange atmosphere that once hid its surface from view.

During descent, Huygens captured a fish-eye view from about 3 miles (4.8 kilometers) up that showed a textured world below.

What the Titan Huygens probe did

One of the key figures behind the mission was Dr. Jean-Pierre Lebreton of the European Space Agency. He served as Huygens Mission Manager and Project Scientist.

Huygens separated from Cassini and rode a sequence of parachutes for about 2.5 hours as it fell through Titan’s haze. That planned descent balanced speed, stability, and power so the instruments could work all the way down.

The probe sent a steady stream of data to Cassini and, after landing, transmitted from the surface for about 72 minutes while returning roughly 350 images. Engineers then relayed everything home once Cassini had line of sight to Earth.

Huygens carried three core science packages that shaped what we learned. The “Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer” mapped the landscape and sky, the “Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer” sampled the air, and the “Surface Science Package” tested the ground.

How Huygens landed on Titan

Parachutes slowed the craft in stages, with the main canopy swapped for a smaller one around 75 miles (120 kilometers) above the surface.

That switch kept Huygens from drifting too far while giving it time to observe the air below the haze.

Close to the ground, the DISR cameras stitched views from several altitudes and revealed organized patterns rather than chaos. Those images showed networks that look like channels and basins shaped by flowing liquid.

The landing itself was gentle compared with expectations. A small lamp even illuminated the surface for more than an hour, helping the cameras and spectrometers see subtle differences in the material nearby.

Signals reached large radio telescopes on Earth as a faint tone, a reassuring sign that the spacecraft was healthy.

After Cassini moved beyond Titan’s horizon, contact ended and the mission’s short window of surface time was over.

What we learned about Titan

The GCMS made direct atmospheric measurements during the descent and after touchdown.

Titan’s air turned out to be mostly nitrogen with a significant amount of methane. The data gave additional clues about how these gases cycle over time.

Ground interaction data showed that Titan’s surface behaved like a relatively soft solid rather than hard ice or deep liquid.

The probe pressed into a thin crust and then settled, consistent with a damp, mechanically weak layer below.

DISR mosaics pointed to narrow channels running from brighter highlands into darker lowlands. They ended in basin-like areas that resemble dry lake beds, with raised spots that look like islands and shoals.

Putting the pieces together suggested a methane-based weather cycle that can leave the ground wet, then dry again.

Temperatures near the surface hover around minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit (-180 degrees Celsius), so water there exists as rock-hard ice while methane can be liquid.

Why this first image still matters

For planetary science, a single touch on the ground changed how we read the rest of Cassini’s orbital data.

Orbiter images and radar maps benefit from a known landing site and local textures, which anchor interpretations of distant terrain.

Huygens also demonstrated how parachute descents can work in thick, cold atmospheres beyond Earth. That success boosts confidence for future probes that must balance power, heating, and communications far from the Sun.

The mission’s short surface session delivered chemical and physical constraints that models alone could not supply.

Those real numbers inform questions about Titan’s interior, its methane sources, and whether it hides subsurface reservoirs.

It also showed how international collaboration can deliver precise, hard-won results at extreme distances. NASA, ESA, and the Italian Space Agency (ASI) split roles effectively, then stitched the data into a coherent story.

What comes next for Titan

Future plans aim to sample Titan’s chemistry in more places and at more times. A flying laboratory could survey dunes, ancient channels, and impact sites to compare compositions and textures across dozens of miles.

Scientists want to time observations with seasonal shifts to see how methane clouds, rain, and fog change.

That type of cadence would help separate one-off events from recurring patterns. Engineers also study how to keep electronics warm and reliable in bitter cold.

Missions like this take decades to bring to fruition, from idea to touchdown, and the total visual record obtained lasted only 72 minutes. However, Huygens remains the only probe to land on a world in the outer solar system.

Click here for more information about the Huygens probe and Cassini mission…

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–