New giant-eyed octopus discovered in an Australian underwater canyon

A deep sea octopus with strikingly large eyes has joined the tree of life. It was hauled from a canyon off northwestern Australia during a monthlong research cruise and brought aboard for careful study.

Scientists have given it the formal name Opisthoteuthis carnarvonensis, commonly called the Carnarvon flapjack octopus. It lives far below the surface and carries a soft, dome shaped body with thick arms.

Meet Opisthoteuthis carnarvonensis

The species was described by Tristan Verhoeff of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) after specimens were collected aboard the RV Investigator during a late 2022 voyage off Western Australia.

The cruise covered deep habitats in and around canyon systems that cut into the continental slope.

“A new species, Opisthoteuthis carnarvonensis sp. nov., is described from five specimens collected off northwestern Australia,” wrote Verhoeff.

The animal looks like a small parachute when relaxed. It has a gelatinous, dome-like body, eight thick and relatively long arms lined with dozens of suckers, very large eyes, and small fins set near the back of the mantle.

Life in a canyon far below sunlight

The first specimens came from an underwater canyon within Carnarvon Canyon Marine Park (CCMP) off the northwest coast. That protected area features long, deep channels carved into the continental margin.

This octopus appears to stick close to the seafloor rather than roam the open water. It has so far been found only in a small patch of the Indian Ocean, suggesting a limited range that future surveys may expand.

Hauls that brought it up were part of a broad biodiversity survey, not a single species search. Researchers used standardized gear to sample invertebrates and fishes, then sorted unusual finds for expert identification.

Opisthoteuthis carnarvonensis is unique

The Carnarvon flapjack octopus belongs to Opisthoteuthidae, a family of finned deep sea octopuses within the cirrate suborder that differs from common shallow water octopuses in body plan and lifestyle.

Cirrates tend to have soft, buoyant bodies, modest fins, and webbing between the arms that forms a single umbrella of skin.

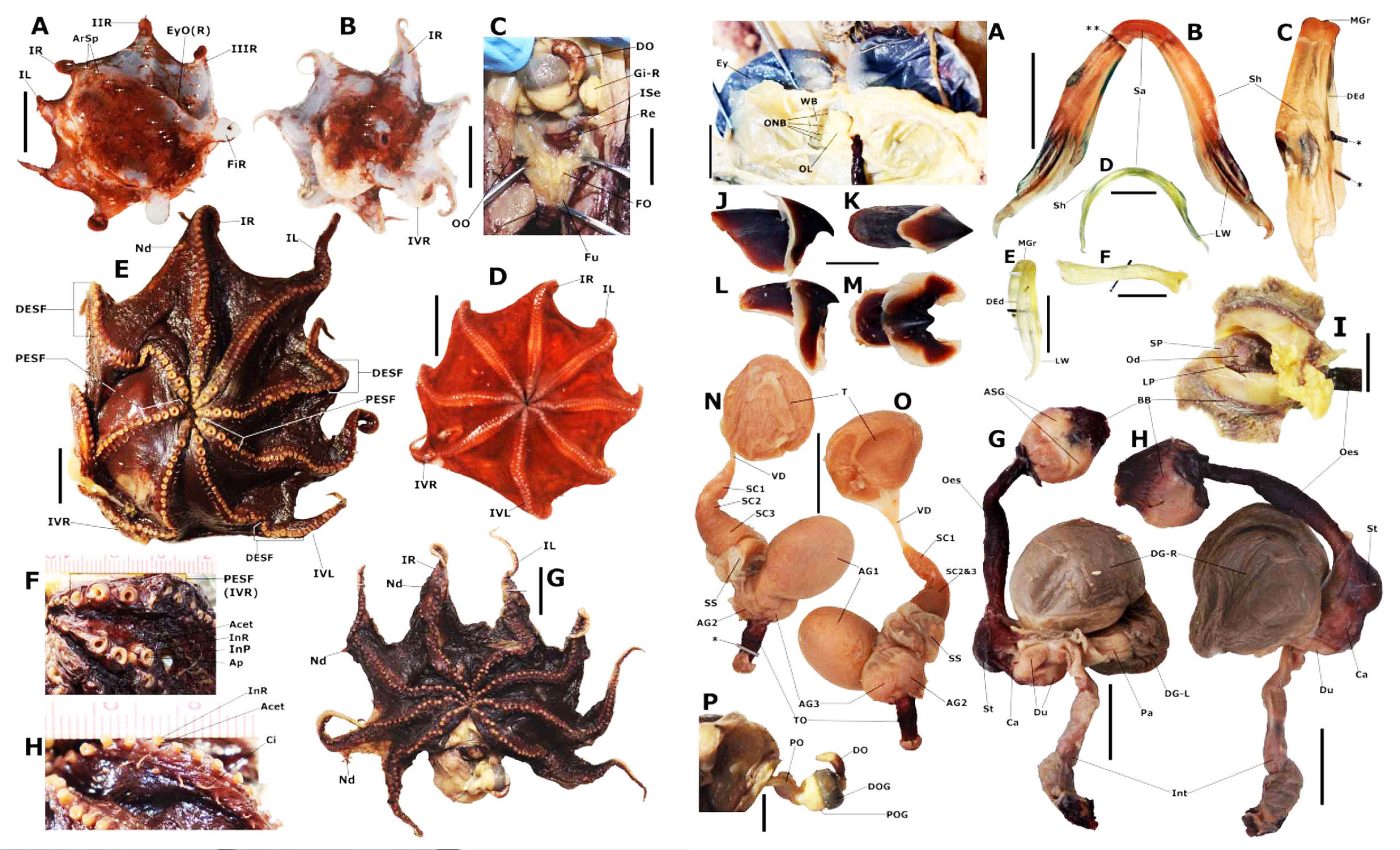

Verhoeff diagnosed the new species using internal anatomy and subtle external traits. Key features include very large eyes relative to mantle length, a bilobed digestive gland, and distinctive patterns in the arm sucker fields.

Mature males carry two special areas on each arm called the proximal enlarged sucker field and the distal enlarged sucker field.

The arrangement, size, and position of these enlarged suckers, along with the presence of small web nodules on the arm edges, helped separate O. carnarvonensis from lookalikes in nearby waters.

Why this description matters

Describing a species is more than naming it. A careful diagnosis anchors the organism in the scientific record, links it to museum specimens, and lets others confirm identifications without guesswork.

The paper also clarifies the wider deep sea octopus fauna in the region.

It recognizes material consistent with Opisthoteuthis cf. philipii in northwestern Australia and Indonesia, and re describes O. extensa, moving it into Insigniteuthis based on male sucker field patterns.

These steps improve how scientists tell similar species apart. They also feed into better identification keys and databases, which can be used by survey teams, fisheries observers, and conservation planners.

From ship to science, connecting the dots

The voyage that retrieved these octopuses ran from November 19, 2022 to December 19, 2022 and mapped habitats from shallow shelf to very deep slope while sampling sharks, fishes, and invertebrates.

CSIRO reports that many animals from the deeper stations are likely new to science, a reminder of how much remains undescribed in Australia’s offshore parks.

Marine parks are set up to safeguard habitats and the species that rely on them.

When a new animal is formally described, managers can fold that knowledge into site plans and monitoring goals, especially for habitats that are difficult to access.

Good taxonomy also reduces confusion in ecological studies.

If researchers can match beaks, sucker patterns, and other hard to change features to named species, they can track diets, ranges, and population changes with more confidence.

What we still do not know

Little is known about the behavior of this octopus in the wild. Its soft body and webbed arms hint at slow, energy efficient movement near the seafloor rather than bursts of speed.

Reproduction is another open question. Species related to Opisthoteuthis carnarvonensis show prolonged, low output spawning with a few eggs maturing at a time, but this species will need direct observation to confirm anything similar.

Future work could add genetic data to the picture, link larvae to adults, and reveal how far these octopuses spread along the canyon network.

Live video from deep submersibles would also help answer simple questions about feeding, courtship, and daily activity patterns.

The study is published in the Australian Journal of Taxonomy.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–