6,000-year-old piece of chewing gum is discovered in the Alps

About 6,000 years ago, people living beside Alpine lakes spat out lumps of black, sticky chewing gum. That gum was birch tar, a pitch made by heating birch bark with very little air.

Now scientists have recovered saliva, food traces, and oral bacteria from these ancient wads using ultra sensitive genetic tools.

By studying about 30 pieces from lakeside villages around the Alps, researchers can see what early farmers ate and repaired.

The work was led by Anna E. White, an archaeologist and geneticist, at the University of Copenhagen. Her research focuses on how ancient DNA, genetic material preserved in old remains, can reveal everyday life in past societies.

These villagers lived in the Neolithic, a late Stone Age period when farming and pottery spread across Europe. They built wooden houses on stilts along the lakes, and relied heavily on birch trees for fuel, building, and sticky tar.

Chewing gum made of birch tar

Birch tar is not just a curiosity from one village, it is the oldest known synthetic material in Europe. Recent work shows that people have been making and tuning this adhesive since Neanderthal times, using different methods to change its strength.

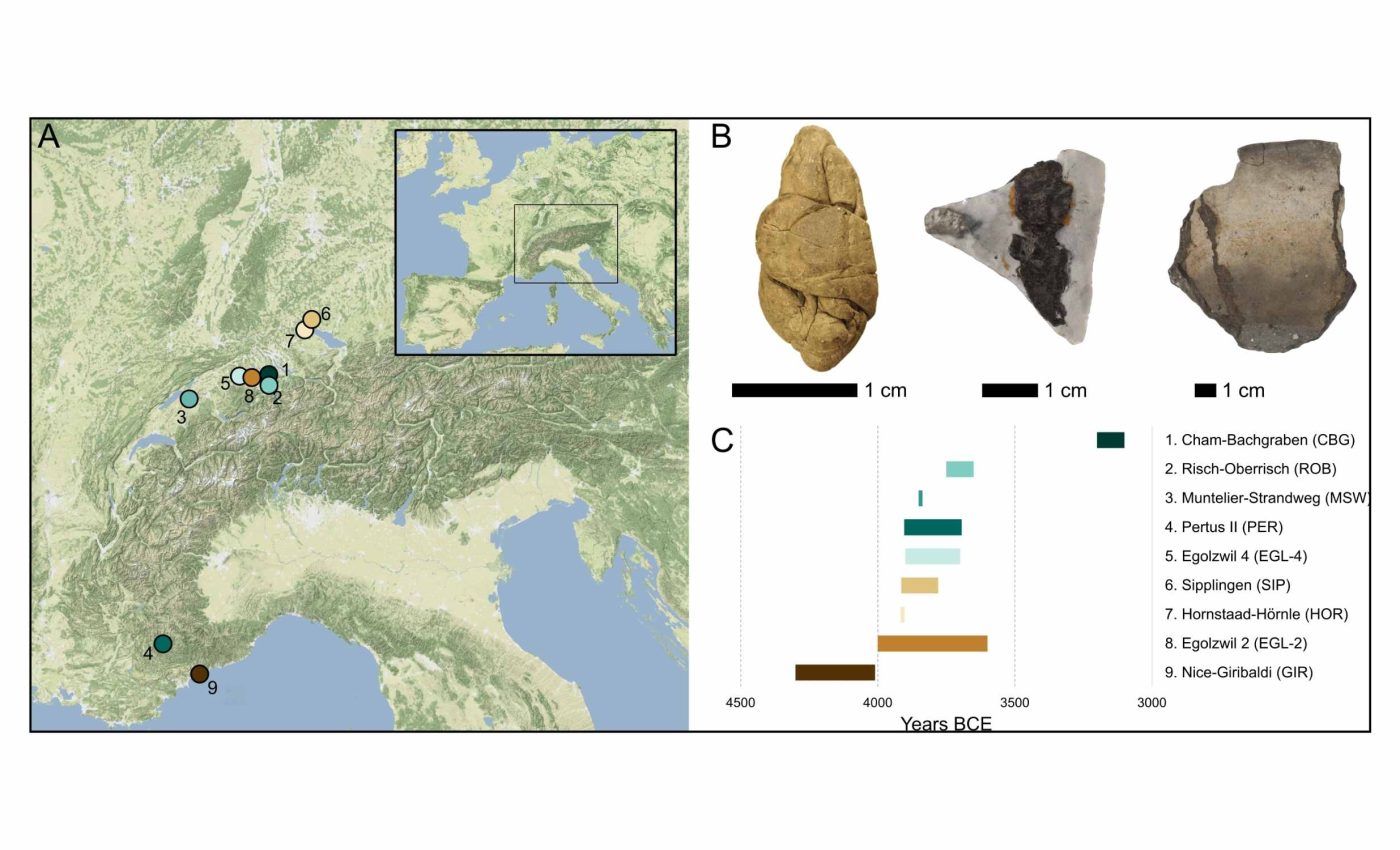

In this Alpine research, the team examined 30 tar lumps from nine sites, scraped from tools, cracked pots, and loose chewed pieces.

They combined chemical biomarkers, chemical clues that flag birch tar and resins, with ancient DNA from humans, plants, and microbes in the same samples.

Some loose pieces had clearly been chewed and then set aside near the fire. Others seem to have been chewed to soften them before pressing the warmed tar into cracks, handles, or seams.

Secrets in the birch tar gum

Several lumps show clear tooth marks and hold enough human DNA to identify both male and female chewers. Alongside that human signal, the chewed pieces include a rich oral microbiome.

Plant DNA from wheat, barley, peas, hazel, beech, linseed, and poppy clings to the tar, probably carried in from very recent meals.

Together they show that early Alpine farmers mixed crops with gathered foods such as nuts and tree seeds, instead of abandoning wild resources.

A few tar spots used to repair pots carry DNA from peas and hazelnuts, tying particular vessels to storing or cooking those foods.

That kind of match between residue and object helps link specific containers to cereals, pulses, or nut based dishes.

Sticky repairs and custom glues

Other tar traces sit along cracks in pottery or between stone blades and wooden handles, where they served as a strong waterproof glue.

Some samples show many degradation markers, chemical byproducts that form when tar is repeatedly reheated, so people probably warmed and reused the same adhesive.

In a few lumps the team detected extra resin from conifer trees such as pine. Mixing birch tar with this resin let Neolithic crafters tune the glue for jobs like tool hafting, crack sealing, or waterproof coatings.

Tar scraped from repaired pots holds more degradation products than tar from tools or chewed pieces, suggesting hotter heating during cooking.

That chemical pattern fits a picture where pot repairs sat close to open flames, while tool adhesives avoided the same repeated stress.

Food, animals, and microbes

The plant and animal DNA trapped in the tar lines up well with other evidence from Neolithic lake villages in Switzerland and beyond.

Archaeobotanical research on waterlogged Alpine sites finds cereals grown alongside hazelnuts, acorns, and fruits, matching the mix seen in these chewed samples.

Wild boar and fish DNA sticks to tar on some arrowheads, hinting that the same arrows were used on land and in water. Sheep DNA appears on one repaired pot, pointing to a past use in storing or cooking sheep milk or meat.

People, chores, and skeletons

Alpine lake settlements rarely yield skeletons, because bones rot away in wet soil, but tar survives and quietly stores human DNA for millennia. This gives researchers a way to learn about ancestry, sex, and even health without finding a single grave.

“This study underscores the value of integrating organic residue and ancient DNA analysis of archaeological artifacts,” said White.

Her team’s approach shows how much personal information can survive in materials that were once treated as simple glue.

In this tiny dataset, male DNA appears most often on tool adhesives, while female DNA turns up more on tar used to mend pottery.

The pattern is not final, but it hints that repairing pots, chewing tar, and fixing tools were not shared equally by men and women.

Earlier study on a 5,700 year old chewed birch pitch from Denmark showed that this material can hold a human genome and mouth bacteria.

Together with the Alpine samples, it points to chewed tar as a source for tracking how people, diets, and microbes shifted through deep time.

Lessons from birch tar gum

Modern lab work shows that birch tar contains phenolic compounds with strong antibacterial effects against several kinds of microbes.

That chemistry helps explain why Neolithic people may have chewed tar for mouth hygiene or aches, and to soften glue before use.

Altogether, these black lumps show how Europe’s first farmers used chemistry, craftsmanship, and recycling to squeeze value from local trees.

A scrap someone once chewed while working beside a lake now carries details of their dinner, tools, and social world.

The study is published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–