Map shows 5,500 toxic hotspots in the US that could turn into disaster zones

About 5,500 toxic sites along U.S. coasts could end up in floodwater as oceans rise this century. A new study finds that marginalized communities could be threatened by a burden of toxic waste.

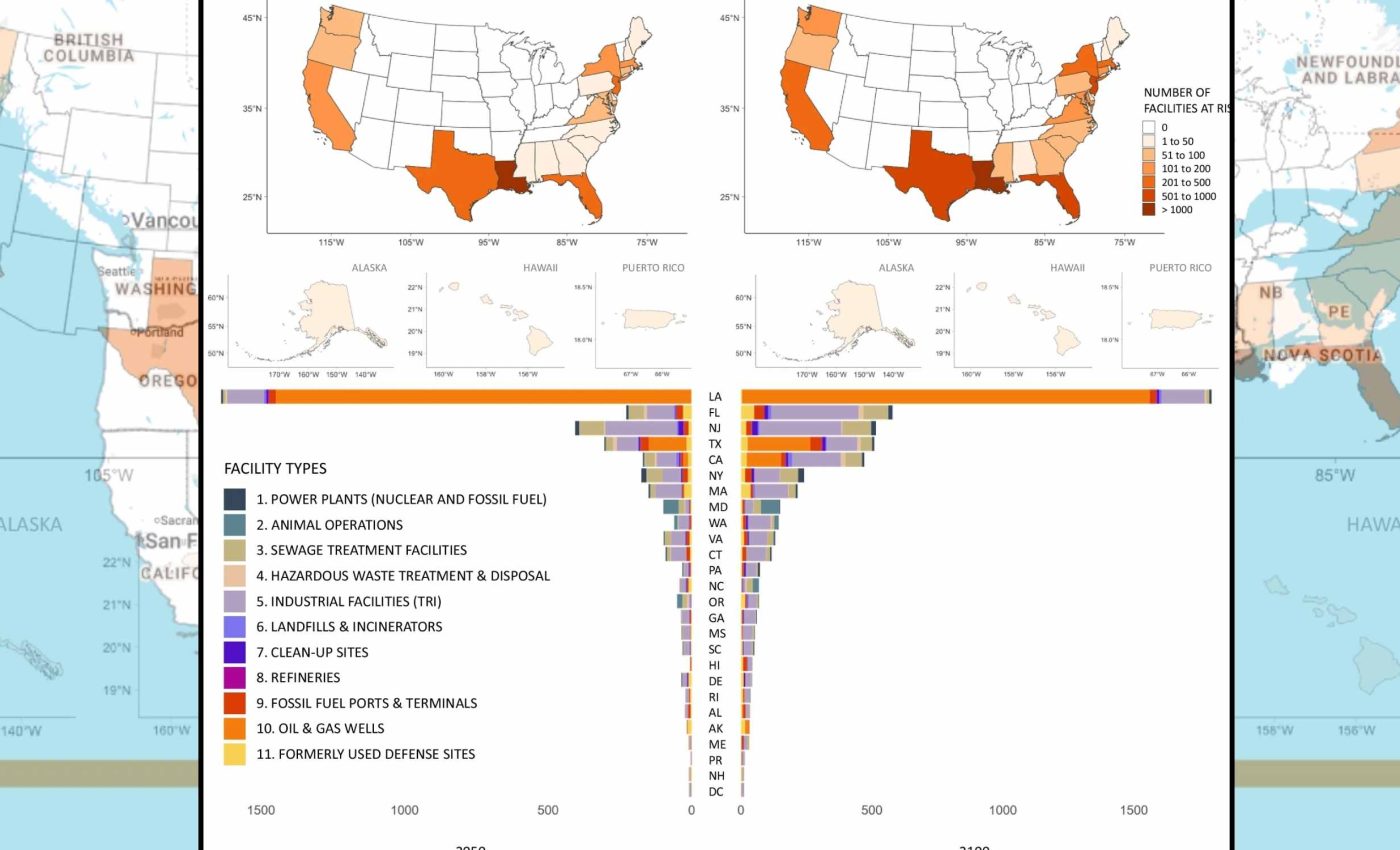

Researchers mapped facilities that handle sewage, fuel, and hazardous waste across 23 states and Puerto Rico. Their aim was to see whether rising seas could flood them.

They found that many sites sit next to neighborhoods already burdened by pollution, poverty, or language barriers and often limited political power.

Toxic waste sites meet rising seas

Global sea level rise, the gradual increase in average ocean height, is speeding up as glaciers melt and warmer water expands around the world.

Along U.S. coastlines, a federal assessment projects roughly 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 centimeters) of extra water height by 2050, even if emissions start to fall.

The study estimates that many facilities handling sewage, fuel, or hazardous waste will face coastal flooding by 2100 if emissions remain high. Greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels lock extra heat into the climate system.

Work on this project was led by Lara Cushing, an associate professor of environmental health sciences at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA). Her research focuses on how environmental hazards and climate change shape health risks in marginalized communities across the U.S.

Her team examined tens of thousands of coastal hazardous sites in the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Data from digital maps showed that over half of the flagged sites could face flooding by 2050. Moderate emission cuts would spare 300 facilities of these facilities by 2100.

Why certain communities carry more risk

The team also examined who lives near these facilities. They compared data from flood-exposed neighborhoods and similar coastal areas that lack hazardous sites. They found that neighborhoods with more renters, poverty, and language barriers were more likely to sit near these toxic waste sites.

Such neighborhoods had between a 19 and 41 percent higher risk of having a flood-exposed facility nearby.

The federal Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool maps disadvantaged neighborhoods nationwide. Data from this system showed that these communities had 50 percent higher odds of hosting at least one flood-exposed site.

Those patterns echo decades of environmental justice research, investigations on how pollution and climate risks fall unequally on different groups.

This is especially so for black residents nationwide. Across the country, discriminatory zoning and housing policies have pushed many communities of color and low income families into the shadow of refineries, ports, and landfills.

A previous study had classified sites that were potential toxic hotspots. Those that were considered at risk of toxic flooding included 22% of coastal sewage treatment facilities, and 24% of refineries. In addition, 44% of fossil fuel ports and terminals, and 12% of industrial facilities were identified as at risk.

Finally, 30 percent of fossil fuel and nuclear power plants were at risk, along with 21% of formerly used defense sites. Floodwaters from these sites could carry oil, chemicals and wastewater.

Flooded toxic waste sites can affect health

“People exposed to flood waters near industrial animal farms or sewage treatment plants could be exposed to bacteria like E. coli,” said Sacoby Wilson, a professor at the Maryland Institute for Applied Environmental Health at the University of Maryland who studies pollution risks in frontline communities

Floods near refineries, power plants, or industrial sites can wash metals and toxic chemicals into neighborhoods. These substances may cause rashes, eye irritation, headaches, or fatigue. Experts note that people with underlying health conditions can experience worse symptoms during these flood events.

Repeated exposure to contaminated water, soil, or air near these sites can damage the liver, kidneys, or lungs. Some of the substances can raise cancer risks.

These pollutants also interfere with hormones and reproduction. This means that a single flood can leave invisible health problems that last for years.

Hurricane Harvey showed just what can happen when industrial regions flood. Storms such as this push water into the petrochemical corridor around Houston and nearby communities.

One report found that over two million pounds of pollution and 150 million gallons of wastewater spilled from Houston facilities after the storm.

Toxic waste lessons

For emergency planners, the study highlights how climate change can turn routine floods into chemical disasters unless facilities are strengthened or moved. Experts argue that governments at every level need to build risks into hazard mitigation plans and disaster drills, not wait for the next storm.

Cutting emissions matters, because the authors found that moderate action would keep about 300 hazardous sites from crossing the flood risk threshold by 2100.

Different research has shown that a sea-level rise of even one foot (30 centimeters) can expose dozens of treatment plants and leave millions without sewage service.

For the most exposed sites, options include elevating equipment, building higher flood barriers, and moving tanks farther inland. In some cases the relocation of an entire plant may be necessary.

Communities living nearby can push for oversight and transparent data about flood risks. They can also emphasize the need for emergency warning systems, and cleanup of legacy contamination before water reaches chemicals.

The new work ties together climate physics, toxic infrastructure, and social inequality. This highlights that t flood risks are not just about waves reaching front doors. Instead, it warns that where toxic sites sit today will shape who breathes, drinks, and lives with the pollution released as sea levels rise.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–