Biochar reshapes how soil microbes pull carbon from the air

Soil often feels like background material. People walk over it, plant into it, and rarely think further. Climate conversations usually skip past it in favor of forests, oceans, or new technology.

That gap matters. Soil does not just hold carbon that plants leave behind. It runs active biological processes that shape climate outcomes every day.

Microbes living underground pull carbon dioxide from the air and convert it into organic matter, without sunlight and without leaves.

A recent study brings this hidden process into focus. It shows how soil type, plant roots, and biochar shape microbial carbon fixation in farmland.

The work also challenges how carbon storage strategies usually frame agricultural soils.

How soil microbes capture carbon

Most soil carbon studies follow plant pathways. Carbon enters soil through roots, residues, and organic inputs. Microbes then break down and recycle that material.

Autotrophic microbes work differently. These organisms fix carbon dioxide directly, using chemical energy instead of sunlight. The process relies on the Calvin cycle and the enzyme RubisCO, the same enzyme plants use.

This pathway runs quietly in agricultural soils. Until recently, few studies measured its scale or drivers. The new research changes that picture by tracking the genes behind microbial carbon fixation in real field conditions.

Genes reveal carbon fixers

The researchers focused on two microbial genes, cbbL and cbbM. Both encode forms of RubisCO, but each functions under different environmental conditions.

Microbes carrying cbbL appeared across all studied soils. This group drove most carbon fixation activity in both systems. Microbes with cbbM showed lower abundance but strong links to high enzyme activity under specific conditions.

Gene-level analysis allowed the team to connect microbial identity with function. Instead of guessing which microbes mattered, they measured activity directly through molecular signals and enzyme assays.

Wet soils favor carbon capture

The study compared flooded rice paddies with well-aerated upland croplands. These systems differ sharply in oxygen availability, water content, and redox chemistry.

Rice paddies supported far higher microbial carbon fixation. Flooded soils created chemical gradients that favored autotrophic microbes. Shifting redox conditions supplied energy sources unavailable in dry soils.

“Our results show that paddy soils, especially around plant roots, are hotspots for microbial carbon fixation,” said corresponding author Xiaomin Zhu of Aarhus University.

“These microbes are actively capturing carbon dioxide in ways that have been largely ignored in soil carbon research.”

Upland soils still supported carbon fixing microbes, but at lower levels. Oxygen-rich conditions changed which microbial groups could thrive.

Roots amplify microbial work

Plant roots played a central role in both systems. The rhizosphere, the narrow soil zone surrounding roots, emerged as a key site for microbial activity.

Roots release organic compounds into nearby soil. These exudates feed microbes and alter local chemistry. In flooded rice soils, this interaction became especially important.

RubisCO enzyme activity peaked near roots rather than in bulk soil. This pattern showed that plant-microbe interactions amplify carbon fixation even when microbes rely on carbon dioxide rather than plant carbon.

The rhizosphere functioned as a biological hotspot. Small areas delivered high levels of biochemical activity.

Biochar changes soil microbes

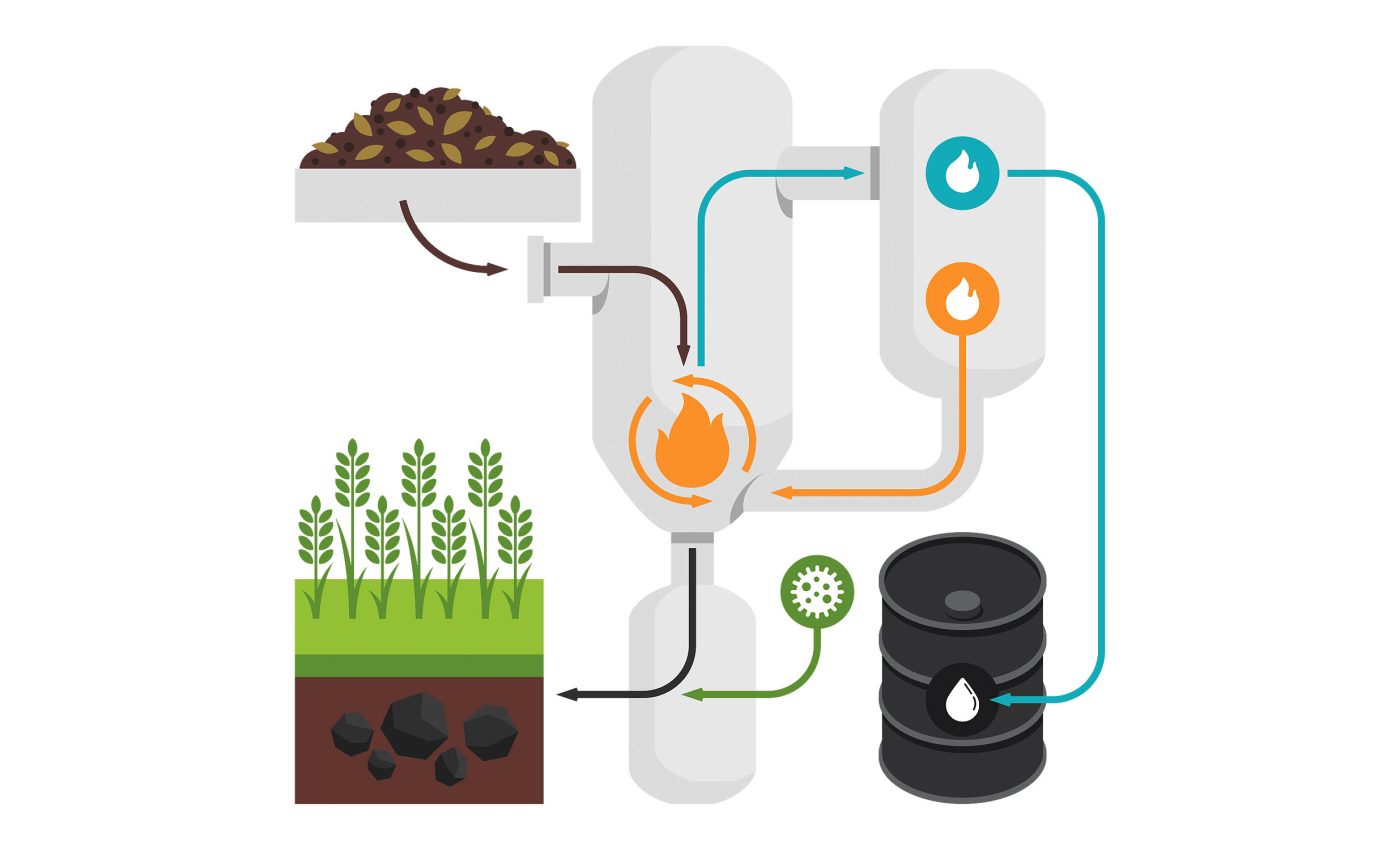

Biochar entered the experiment as a widely promoted soil amendment. Farmers use it to improve soil structure and increase carbon retention. It forms when crop residues heat under low-oxygen conditions.

The results showed no simple outcome. Biochar did not boost carbon fixation across all soils. Instead, it reshaped microbial communities in specific ways.

In paddy soils, biochar reduced microbes carrying the cbbM gene. These microbes often link to high RubisCO activity under low oxygen conditions.

“Biochar does not just add carbon to soil,” Zhu explained. “It changes which microbes are active and how carbon flows through the soil system. That can create tradeoffs between different microbial pathways of carbon fixation.”-

The findings highlight context dependence. Soil type and water regime shaped biochar effects more than the material itself.

Nutrients steer soil microbes

Microbial carbon fixation closely connected with nitrogen cycling. Nutrient availability influenced which microbial groups dominated.

In flooded rice soils, inorganic nitrogen and redox potential controlled activity patterns. These factors shaped microbial competition under low oxygen conditions.

Upland soils showed a different set of controls. Microbial biomass and easily available carbon and nitrogen pools mattered more.

Carbon fixation linked tightly with other soil processes. Nitrogen reduction, iron cycling, methane metabolism, and arsenic detoxification all showed connections to microbial activity patterns.

Rethinking carbon underground

The study expands how soil carbon storage should be understood. Microbial carbon fixation operates independently of plant residues. It responds to water management, nutrient forms, and microbial competition.

“These microbes sit at the crossroads of many nutrient cycles,” said Zhu. “Managing soils to support them could deliver multiple benefits, from climate mitigation to improved soil health and crop resilience.”

Biochar remains a useful tool, but no universal solution exists. Its effects depend on soil conditions and farming practices.

Climate-smart agriculture needs to move beyond plant-focused models. Soil microbes perform active climate work every day. Recognizing that role opens new paths for managing farmland, improving resilience, and storing carbon more effectively.

The study is published in the journal Biochar.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–