Where do the elements come from? Life's rarest ingredients were found in the ashes of an exploded star

How did we get here? That has to be humanity’s most fundamental question that, so far, has no clear answer. The first step in solving this puzzle is to figure out the origin of life’s ingredients, also known as the chemical elements.

Think of elements as the “alphabet” of matter. On their own, they’re like single letters – carbon (C), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N). Combine them in different ways, and you can “spell” water, DNA, proteins, and almost everything else.

We know many elements are forged inside stars and in supernova explosions, then scattered across the cosmos. But the origins of some crucial elements have long remained a mystery.

Astronomers used Japan’s XRISM spacecraft and its ‘Resolve’ spectrometer to detect clear X-ray signatures of chlorine and potassium in the debris of a well-known supernova. Potassium appears in the data with extremely high confidence, exceeding the 6-sigma level.

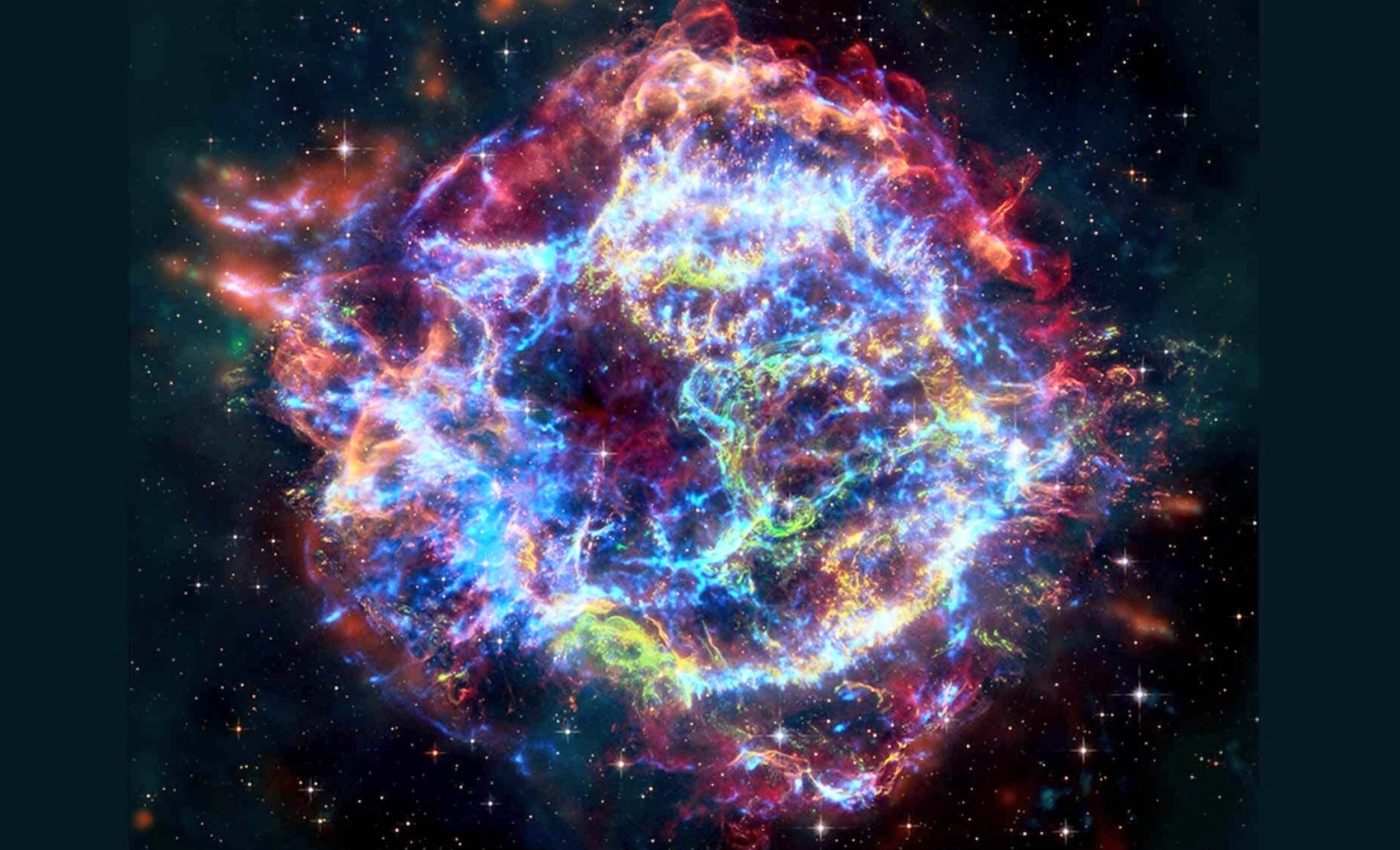

The signals come from Cassiopeia A (Cas A), a supernova remnant, the expanding debris of a dead star inside our Milky Way.

A new study reports that these rare elements appear in far higher amounts than standard calculations predicted.

Stars that seed life on Earth

The work was led by Toshiki Sato, an astrophysicist at Meiji University in Tokyo. His research focuses on high resolution X-ray spectroscopy of supernova remnants and the physics of stellar explosions.

According to a report from NASA, the team connected the stellar deaths to the ingredients of life on Earth.

“When we saw the Resolve data for the first time, we detected elements I never expected to see before the launch. Making such a discovery with a satellite we developed is a true joy as a researcher,” study author Toshiki Sato enthused.

“This discovery helps illustrate how the deaths of stars and life on Earth are fundamentally linked,” said Sato.

These lines were measured in the southeast and northern parts of the remnant, where the debris is richest in oxygen and silicon.

The observed pattern points to turbulent interiors shaping what a star makes before it dies.

Why odd elements matter

Chlorine and potassium are odd-Z elements, elements with odd proton counts.

These elements are practical and familiar. Chlorine helps form salts, while potassium supports nerve signals and the activity of heart muscle.

Stars usually forge even-numbered elements more easily, which is why odd ones tend to be scarce.

Cas A, however, breaks that rule, displaying ratios close to solar values – roughly 1.3 for potassium relative to argon, and about 1.0 for chlorine relative to sulfur.

Odd-numbered elements form through fragile balances of neutron and proton captures that shift with temperature and mixing. That sensitivity makes them valuable tracers of a star’s otherwise hidden interior.

Clear supernova signals

XRISM’s Resolve spectrometer uses a microcalorimeter, a sensor that measures tiny heat changes to read the energy of incoming X-ray photons. It reaches about 5 eV resolution near 6 keV.

Earlier detectors blurred nearby lines into a single lump for decades. Resolve slices those lines cleanly, so faint signals from rare elements are no longer buried.

The instrument is compact but razor-precise, built around a 36-pixel array engineered for accuracy.

By design, it sacrifices wide coverage in favor of the clarity needed to tackle the hardest spectral problems.

Life’s ingredients found in stars

The abundance pattern suggests strong mixing inside the star before it exploded. Likely culprits include fast rotation, binary interactions, or a short-lived shell merger that churned the burning layers.

Cas A itself is a type IIb event, a classification based on a recovered spectrum of the original blast. This type typically points to a star that shed most of its hydrogen envelope, often with help from a companion.

The potassium line is strongest where oxygen rich clumps lie, which fits a pre-explosion origin. The western region shows only weak hints, reinforcing the picture of an asymmetric star.

Seeing chlorine and potassium where theory did not expect them forces a rethink of how stars prepare the periodic table – the list of ingredients used by planets and moons to create life on Earth and elsewhere in the Universe.

The detection also shows what precision X-ray spectroscopy, measuring how matter emits light by energy, can teach us about physics. It ties a local stellar relic to a bigger question about where our salts and nerve signals ultimately come from.

More questions need answers

The team will turn XRISM to other remnants to see if Cas A is typical or a standout. If other sites show the same pattern, then internal mixing is probably a common feature of massive stars.

Modelers now have a firm benchmark for tuning their codes. The results favor scenarios that include rotation, a partner star, or temporary layer mergers deep inside the progenitor.

The map shows a lopsided distribution that aligns with earlier asymmetry hints. The chlorine and potassium enhancements sit well above standard supernova models yet agree with versions that include rotation, companion effects, or shell mixing.

Either outcome teaches something important about galaxy chemistry. A consistent pattern would rewrite our chemical evolution models, whereas a singular case would reveal a star with an exceptional history.

“We are all made of star stuff”

The above quote is one of Carl Sagan’s most memorable lines and a poignant reminder that the elements in our bodies and on the periodic table were forged in the hearts of stars.

Humans are “star stuff” because Earth didn’t make most of the atoms in our bodies. Stars did.

Over millions to billions of years, stars forged elements like carbon and oxygen, then blasted or blew them into space when they died.

That material later gathered into new planets, including Earth, and eventually became part of living things, including you.

Now, billions of years after the first spark of life on Earth, humans like this team from Meiji University are still seeking answers. That’s what makes us human.

“How Earth and life came into existence is an eternal question that everyone has pondered at least once. Our study reveals only a small part of that vast story, but I feel truly honored to have contributed to it,” concluded Kai Matsunaga, a corresponding author of this study.

We may never find the answers we seek, but one thing is for sure – we will never stop searching for them.

The study is published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Image Credit: NASA; ESA; CSA; CXC/SAO; STScI; JPL/Caltech; Milisavljevic et al.; J. Schmidt & K. Arcand

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–