"City under the ice": NASA finds secret base buried in Greenland

The unending stretch of the Greenland Ice Sheet, like a seasoned custodian of countless secrets, has concealed a Cold War-era ice camp beneath its surface.

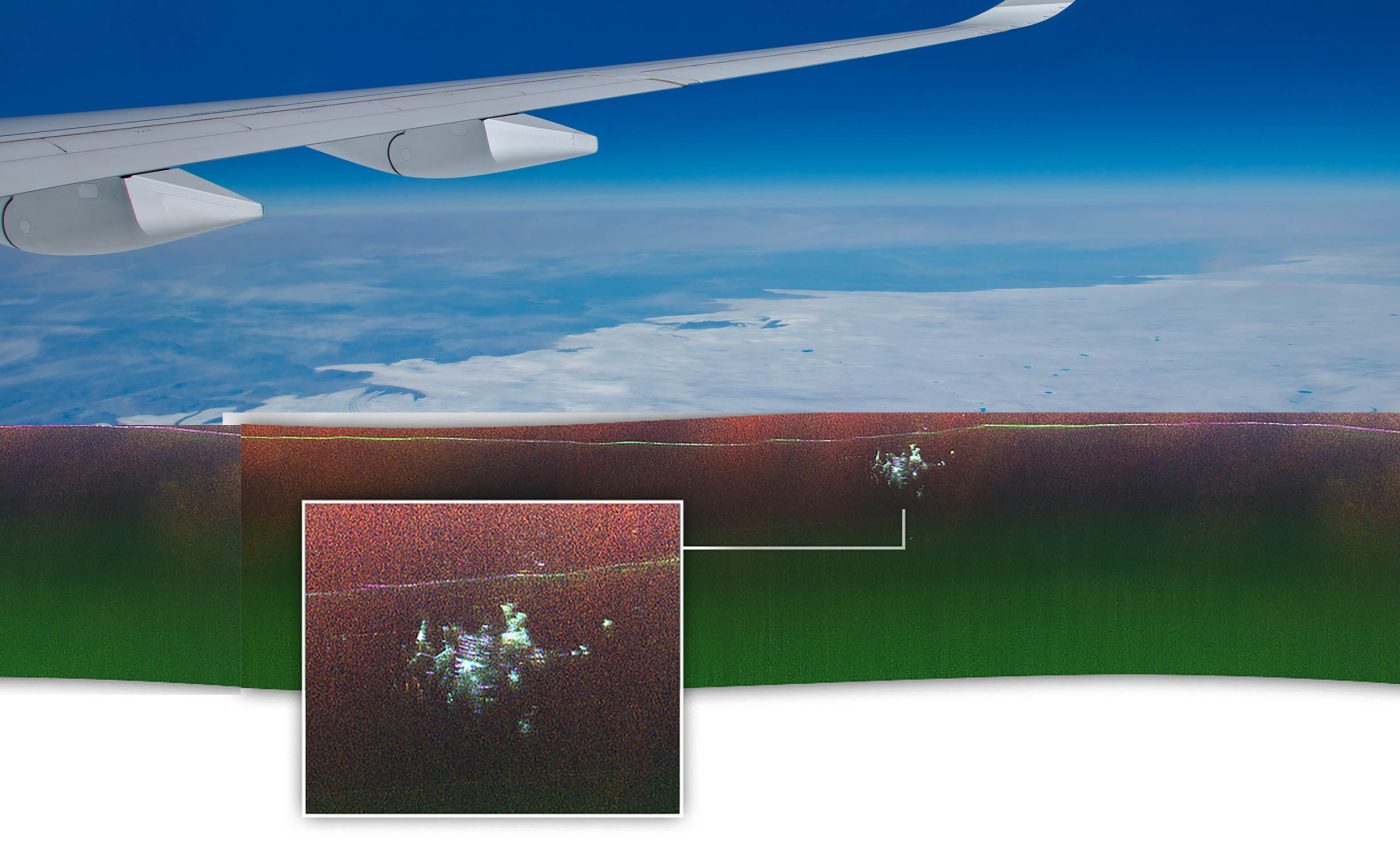

This hidden camp came to light in 2024 when NASA scientist Chad Greene, aboard the Gulfstream III with his team of engineers, embarked on the expedition of a lifetime.

While probing the depths of the ice sheet about 150 miles east of Pituffik Space Base in northern Greenland, the radar readings showed a curious blip that sparked their interest.

The team had identified evidence of the buried remains of Camp Century.

Camp Century: City under the ice

“We were looking for the bed of the ice, and out pops Camp Century,” exclaimed Alex Gardner, a cryospheric scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), who had assisted in spearheading the project.

Camp Century, also affectionately known as the “city under the ice,” is a vestige of the chilling days when the Cold War was in full swing.

Constructed in 1959 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, this hidden military base was etched out within the layers of the ice sheet itself.

Traces of the facility, which has been abandoned since 1967, now lie encased approximately 30 meters (100 feet) beneath the icy surface, waiting to narrate their intriguing past.

What exactly went on at Camp Century?

Camp Century’s main goal was to explore the feasibility of living and operating in extreme cold conditions, which was crucial during the Cold War era.

The base was constructed using large, prefabricated modules connected by tunnels, all insulated and heated to keep the inhabitants comfortable despite the freezing temperatures outside.

About 25 scientists and military personnel lived there, conducting experiments in geology, hydrology, and glaciology, while also testing technologies that could support long-term Arctic missions.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Camp Century is its innovative use of nuclear power.

The base was powered by a portable nuclear reactor, making it one of the first of its kind to operate in such harsh environments.

However, when the base was abandoned in 1967, concerns arose about the disposal of nuclear waste left behind.

Deciphering the indicators

Akin to an ultrasound meant for ice sheets, radar plays a pivotal role in unraveling the truths kept secret by nature.

Radar works on a simple principle – it emits radio waves and times their reflections back to the source. This allows scientists to map out the ice surface meticulously, along with its various internal layers, and the bedrock underneath.

Previous airborne surveys that flew over Camp Century managed to detect signs of the base encapsulated within the ice sheets.

These surveys utilized conventional, ground-penetrating radar that aims directly downwards, which yielded a 2D profile of the ice sheet.

This gave an impression of Camp Century’s solid structures that appeared like an anomaly in the deformed layers of ice.

Generating maps with advanced technology

The April 2024 flights, however, could go a step further with NASA’s UAVSAR (Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar) adorning the belly of the aircraft.

This cutting-edge system introduces a wider angle of view, and looks both downward and sideways, thus generating maps that teem with additional dimensions.

“In the new data, individual structures in the secret city are visible in a way that they’ve never been seen before,” explained Greene.

Determining the camp’s alignment under ice

When juxtaposed with historical maps of the base’s planned layout, the parallel structures demonstrate a striking alignment with the tunnels initially built to house a myriad of facilities.

Yet, the added dimensionality comes with its own challenges in terms of interpretation.

For instance, the long line that seems to appear “above” the base is actually the ice bed, lying at least a mile below the ice sheet’s surface, and well beneath the depth of Camp Century.

This apparent “inversion” is caused by the radar’s return showing part of the ice bed far in the distance.

Camp Century: More than a historical curiosity

Apart from their historical significance, maps created with conventional radar have aided scientists in corroborating estimates of Camp Century’s depth.

This information is crucial in estimating when the melting and thinning of the ice sheet could potentially re-expose the camp and any leftover biological, chemical, and radioactive waste buried with it.

The scientific utility of the new UAVSAR image of Camp Century remains uncertain. For the moment, it’s a novelty – an amazing discovery made purely by chance. However, the principal aim of Greene and Gardner was not to capture this image of Camp Century.

Their principal objective was to “calibrate, validate, and understand the capabilities and limitations of UAVSAR for mapping the ice sheet’s internal layers and the ice-bed interface,” as Greene clarified.

The future of measuring ice thickness

Such instruments hold the key to a future where scientists might efficiently measure the thickness of ice sheets in similar environments in Antarctica. Such data is critical in modeling estimates of future sea level rise.

“Without a detailed knowledge of ice thickness, it is impossible to know how the ice sheets will respond to rapidly warming oceans and atmosphere, greatly limiting our ability to project rates of sea level rise,” Gardner explained.

The test flights that captured Camp Century will undoubtedly usher in the next generation of mapping campaigns focused on ice in Greenland, Antarctica, and beyond.

Image Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–