Climate justice: How current targets let big polluters off the hook

Climate action is falling short, and we’re nowhere close to meeting the promises made to limit global warming.

Under the Paris Agreement, each country is expected to do its “fair share” to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

But new research says the way we’ve been measuring that fair share has a serious flaw – and it’s letting big polluters off the hook.

For years, studies have been comparing countries based on their current emissions, not what they’ve actually contributed to the climate crisis over time.

This shifts responsibility away from those who’ve done the most damage – and pushes the burden onto countries that have done the least.

The research argues that we’ve been using a biased method that “rewards high emitters at the expense of the most vulnerable ones.” The authors say it’s time to stop letting powerful countries rewrite the rules.

Why today’s climate math is unfair

The current system for judging countries’ climate efforts starts from today’s emissions levels, not the bigger picture.

That means it ignores decades – or even centuries – of pollution from rich countries. It also quietly allows emissions to rise before action is taken.

This creates a moving target. If a country pollutes more today, then starts cutting later, the system might still label them “ambitious.” But that’s not ambition – that’s a delay.

Instead, the researchers say we should hold countries accountable right now by using a method based on each country’s historical emissions and financial capacity.

That would reset the playing field. No more coasting for countries that waited too long to start cutting.

It’s a major shift. If applied today, some rich countries would face steep, immediate cuts – not slow and gradual ones.

And since many of them can’t make those cuts fast enough at home, they’d need to fund climate action in poorer countries to make up the difference.

Who needs to do more?

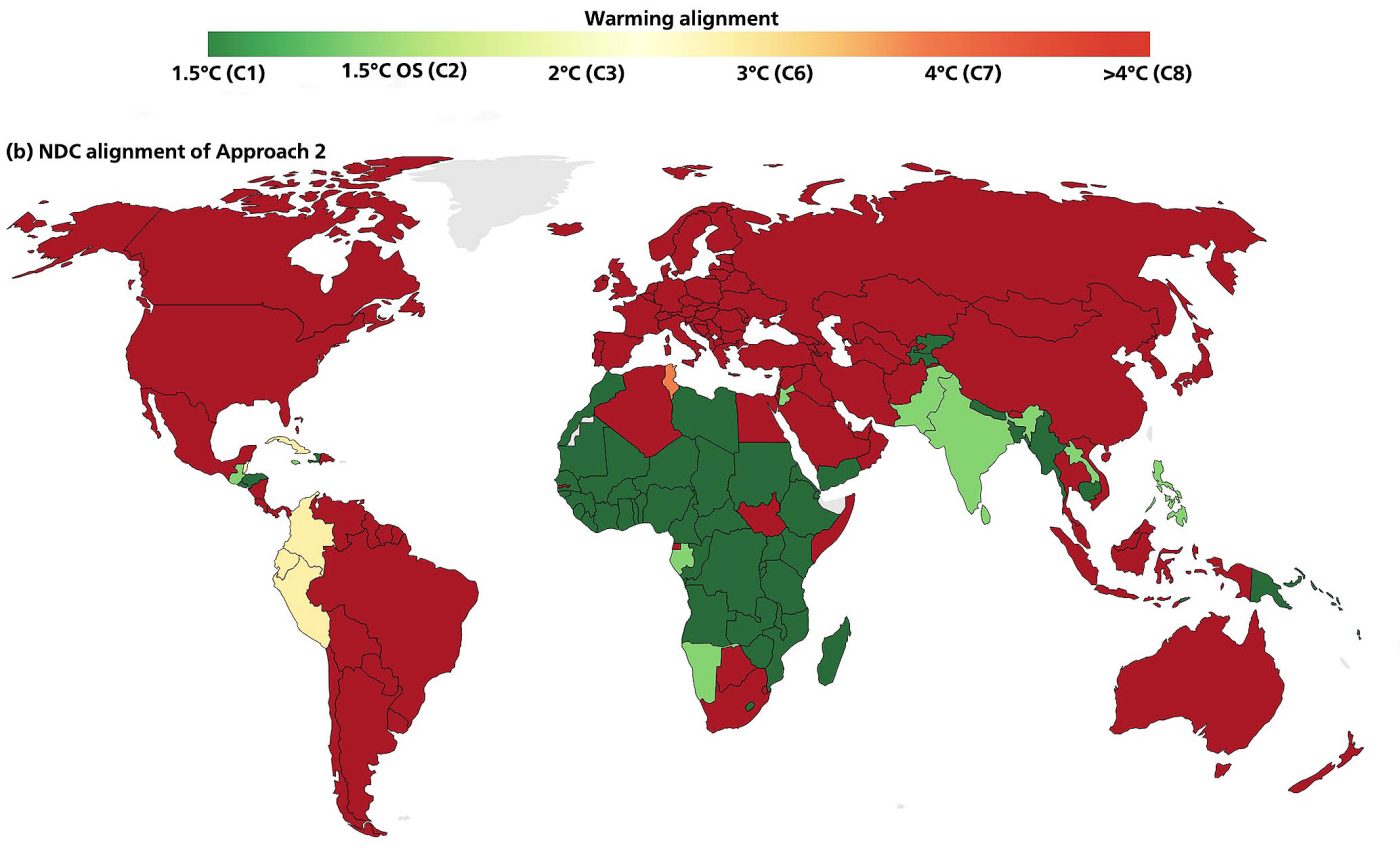

When this new method is applied, the rankings change. High-income countries like the U.S., Australia, Canada, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia show the biggest gaps between what they’re currently promising and what would actually be fair.

Even among wealthy countries, some are putting in more effort than others. But under the current system, those doing less still come out looking good. This study shows how the math hides that inequality.

The team behind the research is based at Utrecht University, led by Yann Robiou du Pont. They propose removing the reward for inaction by changing how we calculate “fair shares.”

It’s not just a technical tweak – it could change how international climate negotiations are judged, and who is seen as doing enough.

Climate action and human rights

Countries have made lots of promises. But what happens when they don’t keep them?Increasingly, courts are stepping up.

They’re becoming an unexpected but powerful player in global climate action. This kind of research plays a key role in those legal battles.

One example is the KlimaSeniorinnen case, where a group of senior women in Switzerland challenged the government over its weak climate policies.

The European Court of Human Rights agreed that failing to take strong climate action is a violation of human rights. Courts now require governments to explain how their pledges are fair and ambitious.

“This strengthens and underscores the growing role of courts in enforcing climate justice,” said Robiou du Pont.

In a major ruling on July 23, 2025, the International Court of Justice confirmed that countries are legally required to prevent serious harm to the climate system. It also said they must act together – and with urgency.

Paying for a fairer climate future

The idea that rich countries should do more isn’t new. Climate justice groups and researchers have been saying it for decades. But this study backs that argument with hard numbers.

The basic message is clear: wealthier countries with the largest carbon footprints need to make deeper cuts and pay more into climate finance. That includes funding renewable energy, climate resilience, and emission cuts in developing countries.

Right now, we’re not seeing that. The lack of fair commitment and financial support from the countries most able and responsible is undermining effective global action.

If those with the most resources refuse to act fairly, it’s unlikely the world will hit its targets. But if fairness becomes the foundation – if efforts and finance are shared based on responsibility and capability – the chances of meaningful progress go up.

This study doesn’t just explain what’s wrong. It shows a way forward that’s more honest, more just, and more effective. And that might be exactly what’s needed to break the current climate deadlock.

The full study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–