Mars orbiters capture closest images of rare interstellar visitor 3I/ATLAS

In early October, astronomers spotted something ancient and mysterious gliding past Mars. It was not a spacecraft or satellite, but a visitor from beyond our Solar System – an interstellar comet.

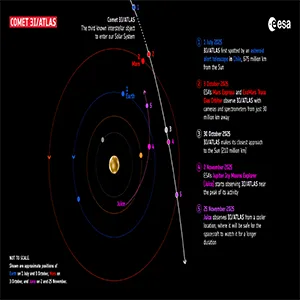

Comet 3I/ATLAS is only the third interstellar comet ever observed. These types of comets are true outsiders from deep space. They were born around a completely different star, long before Earth even existed.

What makes 3I/ATLAS especially intriguing is that the comet might be three billion years older than our entire Solar System.

Caught on camera from Mars

When 3I/ATLAS passed about 18.6 million miles from Mars on October 3, two orbiting spacecraft were ready.

ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) and Mars Express pointed their cameras at the comet, hoping to get a rare view. It was the closest look any ESA spacecraft could get.

The challenge? These cameras were made for imaging Mars: bright, nearby, and relatively easy to photograph.

3I/ATLAS, by contrast, was much dimmer. It was somewhere between 10,000 and 100,000 times fainter than Mars, according to the team operating the CaSSIS camera on TGO (Trace Gas Orbiter).

“This was a very challenging observation for the instrument,” said Nick Thomas, principal investigator of the CaSSIS camera.

Capturing the interstellar visitor

Despite the challenge, the TGO managed to capture a sequence of images showing a faint, blurry white speck moving across the sky.

The tiny dot marked the comet’s center – its rocky, icy core known as the nucleus – surrounded by a glowing halo of gas and dust called the coma.

The camera couldn’t distinguish the small nucleus itself. That would’ve been like trying to spot a cellphone sitting on the Moon from Earth.

The coma was a different story. It’s a cloud of gas and dust released by the comet as it gets heated by the Sun. It can stretch thousands of miles wide. But even that glow faded quickly with distance, so the full size wasn’t clear in the pictures.

Looking deeper with Mars orbiters

Comets typically develop a tail as they approach the Sun. The tail may reach millions of miles in length through space, blown back by solar wind. In the case of 3I/ATLAS, the tail was still too faint to be detected by CaSSIS.

The Mars Express orbiter also attempted to capture the comet. With only half a second of exposure time per image, however, its shots did not reveal anything apparent yet.

The team used instruments on both spacecraft to study the light from the comet. By breaking down that light into its spectrum, scientists might be able to figure out what the comet is made of. But there’s no guarantee the coma or tail were bright enough to give clear results.

“Though our Mars orbiters continue to make impressive contributions to Mars science, it’s always extra exciting to see them responding to unexpected situations like this one. I look forward to seeing what the data reveals following further analysis,” said Colin Wilson, Mars Express and ExoMars project scientist at ESA.

Where did 3I/ATLAS come from?

The million-dollar question is, where did 3I/ATLAS come from? The comet didn’t form anywhere near the planets we know. It came from another star system entirely. Hence, its name starts with “3I,” the third known interstellar object.

The comet was first spotted on July 1, 2025, by the ATLAS telescope in Río Hurtado, Chile. Since then, scientists have tracked it using telescopes on Earth and in space.

Everything in our Solar System was born from the same swirling cloud of gas and dust. This includes planets, moons, comets, and even humans. But interstellar comets like 3I/ATLAS didn’t come from that cloud.

These deep space comets hold clues about alien solar systems – the kind we’ve only seen as tiny dots of light around distant stars.

Getting closer to Comet 3I/ATLAS

Soon, another ESA spacecraft will have a closer look. The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, or Juice, will observe the comet from farther away. That will happen shortly after the comet reaches its closest point to the Sun.

At that stage, it should be more active, meaning more gas and dust, and hopefully, a bigger tail. However, the data from Juice won’t arrive until February 2026.

ESA is also working on a mission called Comet Interceptor, scheduled to launch in 2029. The goal of the mission is to wait in space for a fresh comet from the outer edges of the Solar System, or maybe even another interstellar object.

“When Comet Interceptor was selected in 2019, we only knew of one interstellar object – 1I/ʻOumuamua, discovered in 2017,” said Michael Kueppers, Comet Interceptor project scientist.

“Since then, two more such objects have been discovered, showing large diversity in their appearance. Visiting one could provide a breakthrough in understanding their nature.”

Unfortunately, 3I/ATLAS will not be here for long. It’s currently passing the Sun and will leave our Solar System for good. But with every passing visitor, we learn just a little more about what’s out there.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–