Deep-sea gold rush: Extraction of these small 'rocks' on the ocean floor is causing great controversy

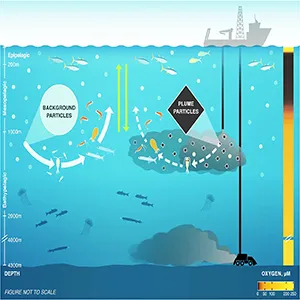

Negative consequences of deep ocean mining activity are no longer found only on the seafloor. This controversial practice has now become a midwater problem as well, with potential impacts reaching hundreds of feet above the ocean floor in every part of the world.

A new study is the first to show that waste discharged from mining ships into the midwater “twilight zone” of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) could disrupt food webs hundreds of feet above the seabed.

Researchers from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa found that more than half of the zooplankton and roughly 60 percent of the micronekton living between about 650 to 4,900 feet (200 to 1,500 meters) would be exposed to mining plumes.

Because these animals feed larger predators, the effects would ripple upward to fish, seabirds, and marine mammals.

Ocean mining plumes replace nutrients

During deep-sea mining, sediment, seawater, and pulverized nodule fragments are pumped to a surface vessel. Nodules are separated, and the waste slurry is returned to the ocean.

Some operators have proposed releasing this waste in midwater to avoid smothering the seafloor.

The new work suggests that choice could backfire. By sampling during a 2022 mining trial in the CCZ, the team showed that discharged particles from ocean mining carry far lower amino acid concentrations than the natural detritus that normally feeds midwater communities.

In simple terms, the plume dilutes the ocean’s “pantry” with low-quality fillers. For tiny, drifting zooplankton already living on slender margins, that swap matters.

Micronekton – small fishes, shrimp, squid, and other swimmers that graze on zooplankton – then pass the deficit up the chain.

Middle of the ocean is vital

The twilight zone is packed with life adapted to darkness and scarcity: krill, lanternfish, siphonophores, gelatinous predators, and more.

Many perform the planet’s largest daily migration, rising toward the surface at night to feed and returning at dawn.

That commute shuttles carbon from the upper ocean to depth, helping regulate the climate. Food in this layer arrives mainly as small, slowly sinking particles from above. Animals here are tuned to that steady trickle.

Replace a meaningful fraction with nutrient-poor sediment and ground rock, and the diet changes without the diners moving.

For plankton that cannot swim away from a plume, exposure is not a choice. For the predators that depend on them, the impact is indirect but real.

Nutrient loss in the deep ocean

The study’s comparison of particle chemistry is key. Natural “marine snow” is rich in amino acids and other compounds midwater life needs. Mining plumes look superficially similar in size and shape but lack that nutritional payload.

The researchers describe the effect as swapping nutrient-dense particles for “empty calories.” In a system where every bit counts, that shift can reduce growth, reproduction, and survival at the base of the food web.

Because micronekton are the main prey for many tuna, seabirds, and marine mammals, even modest losses at depth can echo into fisheries and wildlife far from the discharge point.

Ocean mining rules still unformed

The CCZ spans millions of square kilometers and holds the world’s largest known deposits of polymetallic nodules, rich in cobalt, nickel, and copper for batteries and other low-carbon technologies.

Roughly 580,000 square miles (1.5 million square kilometers) are already under exploration licenses. Commercial mining has not begun, and regulations for where and how to release waste plumes do not yet exist.

The authors argue that this is a narrow window to get the rules right. If midwater discharge becomes the default without understanding its biological costs, the damage could be widespread and long-lasting.

Trade-offs of ocean mining

Where waste is released will shape who is harmed. Plumes sent into the twilight zone could degrade food quality for communities that link the surface to the deep sea, weakening carbon transport and food webs.

Releasing waste near the surface could affect larvae and photosynthetic life as well as spread widely with currents.

Discharging it closer to the seafloor carries smothering risks and could still loft into midwater depending on density and turbulence.

There is no risk-free option, only trade-offs that require solid evidence. The International Seabed Authority is currently debating mining rules, and U.S. agencies such as NOAA will review environmental impacts for any U.S.-linked projects.

Both will need to consider not just seafloor habitats but the full vertical column that mining waste can touch.

Food chains in the crosshairs

Pacific tuna fisheries operate across the CCZ. If midwater prey decline because their food quality erodes, tuna may grow more slowly, shift distributions, or become less abundant.

That would have consequences for nations that rely on tuna economically and for communities that rely on it nutritionally.

Because midwater fauna stitch together ecosystems from surface waters to the abyss, changes in their condition are not easily contained.

Mapping the ocean’s hidden fallout

This study offers a clear starting point: midwater plumes can lower the nutritional value of particles in the twilight zone, and a large share of the resident community will encounter them.

The next steps are to map plume behavior at different depths and discharge rates, track how far and how long particle quality stays depressed, and quantify biological responses across taxa.

Field experiments that pair plume sampling with acoustic and net surveys of micronekton will be especially informative.

Modeling should explore cumulative effects of multiple operations and seasonal changes in background food supply.

A pause before mining

The promise of deep-sea minerals for a low-carbon economy does not erase the ocean’s need for intact food webs.

Until regulators and operators can demonstrate that waste discharges will not starve the twilight zone of the nutrition it depends on, caution is the only credible position.

Choosing mining discharge depths, limiting plume intensity, and, in the longer term, re-engineering processes to minimize waste all belong on the table. The ocean’s middle reaches are out of sight, but they should not be out of the equation.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–