Early Egyptian king named "Scorpion" told his blood-thirsty tales in ancient rock art

Look out over the desert east of Aswan in southern Egypt, and it might seem like there’s nothing but rocks and sand – no sign of the kings who once ruled here. But look closer, and the walls start talking.

Thousands of years ago, long before the famous pharaohs ruled from pyramids, kings carved their power into stone.

These carvings weren’t just decorations. They were public declarations of who was in charge. And they’ve finally gotten the attention they deserve.

Lost rulers carved into stone

More than 5,000 years ago, Egypt was on the edge of something big. Small local rulers had started forming a more connected and controlled territory.

The place we now call Egypt was becoming the world’s first territorial state. It stretched about 500 miles from north to south. That’s not small for a place that had no highways or phones – just boats, legs, and grit.

In the desert valleys like Wadi el Malik and Wadi Abu Subeira, rulers made their presence known with carvings. One of the most fascinating figures from this time was a ruler called Scorpion.

His name appears in rock inscriptions along with a few other symbols, including one that marks it as a place name.

That particular place-name sign is believed to be the oldest one ever found. That discovery made international headlines a few years back. Now, there’s more.

Egypt’s lineup of early kings

Scorpion wasn’t alone. The rocks tell the story of other rulers too. There’s King Bull, who came before him, and Horus-Falcon, who may have been the first in this royal line.

Some of their names reference dangerous animals – centipedes, falcons, bulls – creatures that symbolized strength and fear.

This lineup of names and animal symbols is what researchers call a “royal rock art tableau.” It’s not just a list – it’s a way to show power, legacy, and control over a tough, rugged landscape. These kings wanted people in Egypt to know: This land is ours. We rule here.

Violence and power on display

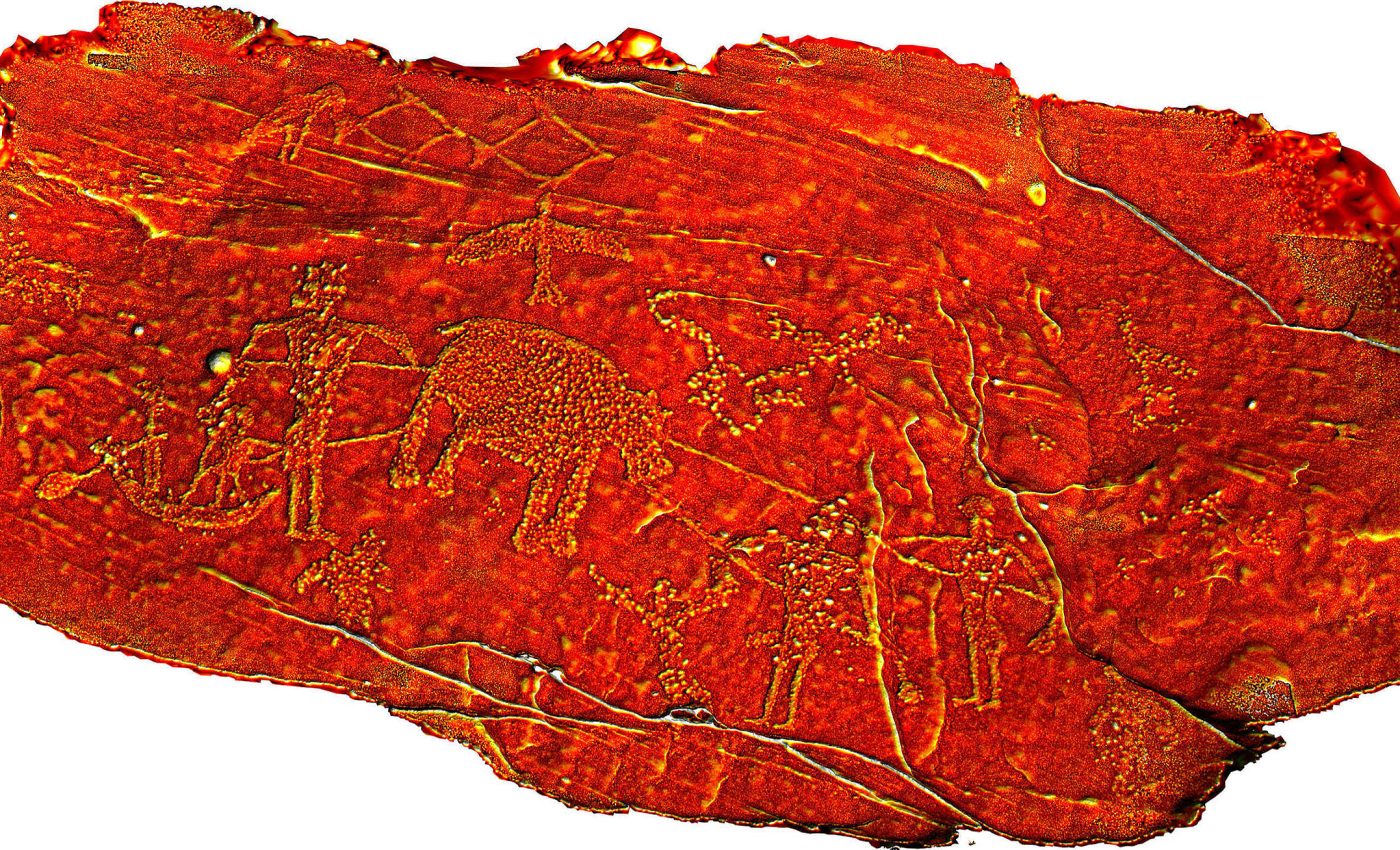

These carvings didn’t shy away from violence. One scene shows a ruler standing over a fallen enemy. In the background, two decapitated heads leave no doubt about the message. These weren’t peaceful monuments – they were warnings.

“The most extreme scene is the one showing the ruler trampling an enemy, with two decapitated heads visible in the background,” said Egyptologist Professor Dr. Ludwig Morenz from the University of Bonn, who has been studying these carvings with his colleague Mohamed Abdelhay Abu Bakr.

Kings carved ties to Egypt’s gods

The kings from this period didn’t call themselves gods. But they made it clear they were close.

They aligned themselves with two powerful deities from the Nile Valley – Bat, a celestial cow often shown with a star-covered face, and Min, a hunting god tied to the deserts and outer regions.

“They formed a divine couple, with Bat associated with the fertile land along the Nile and Min with the peripheral regions as a kind of hunting god,” Morenz said.

The connection to these gods helped build something called “pharaoh-fashioning.” This was how early rulers shaped their image – as chosen leaders backed by divine power. They didn’t inherit power quietly. They carved it in stone.

Trade and faith carved together

At the time, this region was more than desert. It had resources, water, and wildlife. People passed through on hunting trips or mineral expeditions. That made it valuable – and contested. It also made it the perfect spot to mark territory.

“It is actually all about a grandiose presentation of the claim to sovereignty,” Morenz said.

And part of that grand display included religion. One large carving shows a “boat of the gods” being hauled by 25 men. This likely represents a sacred procession that tied the desert valley to the better-known Nile Valley.

Desert valleys served as crossroads

These carvings aren’t easy to see with the naked eye. Thousands of years of wind and sand have taken their toll. But new digital tools have made a difference.

Researchers used high-powered photo analysis to reveal carvings that would otherwise go unnoticed.

“This is an important region when it comes to our understanding of the emergence of the state at the sociocultural periphery in the late fourth millennium,” Morenz said.

It’s clear there’s more to learn here. Compared to central Egypt, this area has barely been studied. But it played a major role in shaping one of the most influential civilizations in history.

Modern scans revived ancient history

Morenz hopes this area will get the attention it deserves. That means more research, bigger projects, and maybe even making the site accessible to visitors.

“I consider this so important that this hot spot should also be made accessible to interested parties with tours and a visitor center,” he said.

What was once forgotten desert might soon become one of Egypt’s most important historical windows. Not just because of what’s carved in stone – but because of what it shows about the earliest rulers who helped create a state that would shape human history.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–