Early hominins were more skilled with their hands than we thought

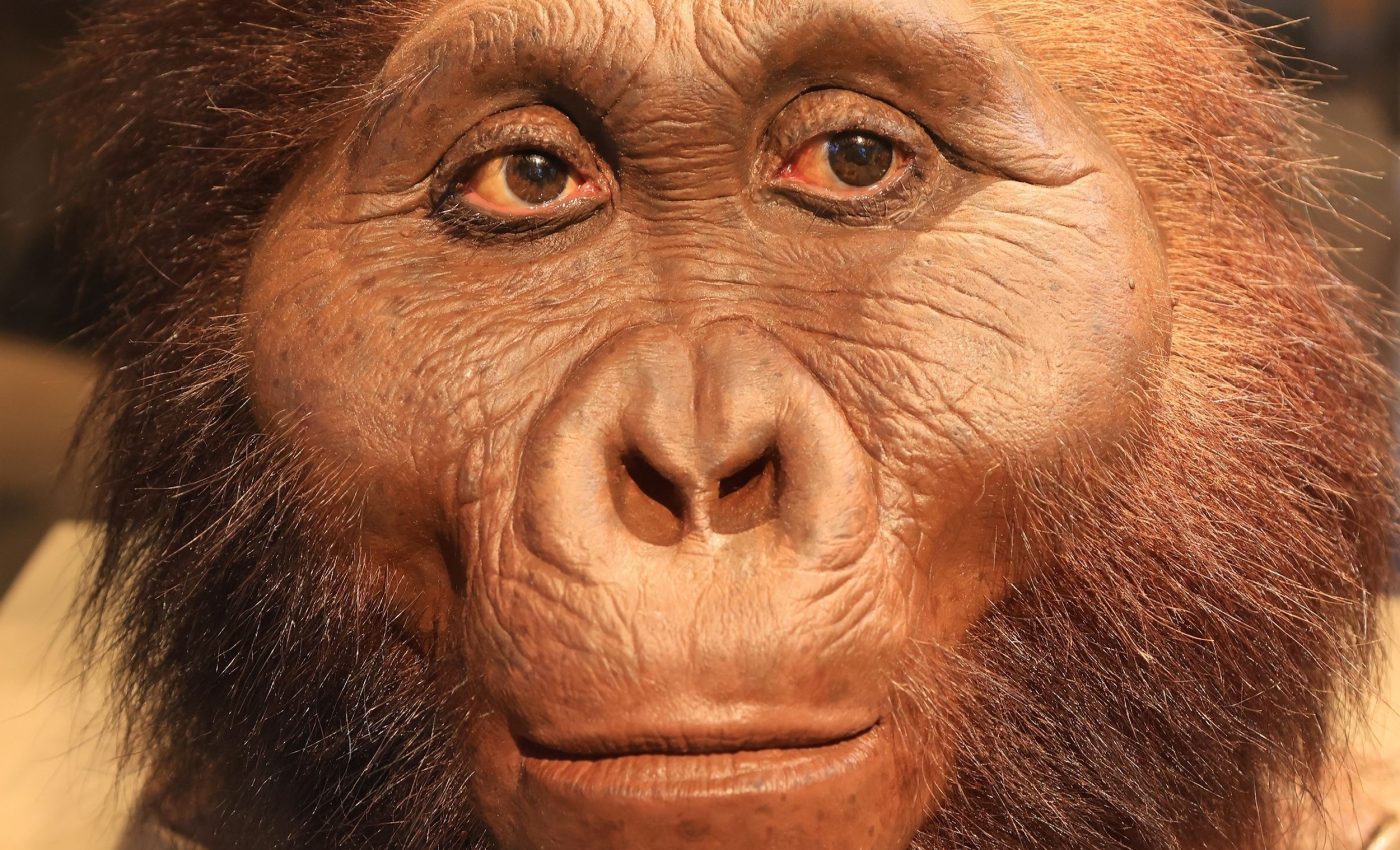

For decades, the extinct hominin Paranthropus boisei has been a bit of a mystery. We’ve analyzed its skulls and seen the massive jaws, but we never had the full picture.

That changed when a newly uncovered fossil in Kenya gave scientists their first real look at the hands and feet of this ancient species. With the new discoveries, some long-standing debates are finally being put to rest.

Ancient hominin Paranthropus boisei

Paranthropus boisei lived over 1.5 million years ago. The hominin was a close evolutionary “cousin” to Homo sapiens, but it wasn’t on the same path that our species took.

Instead, P. boisei developed a powerful build, with a face and teeth made for grinding down tough plant foods. That much was clear from fossil skulls. What wasn’t clear – until now – was whether this species also made and used tools.

Fossil sites in East Africa have often turned up both Homo and Paranthropus bones alongside stone tools. But without hand bones to study, scientists couldn’t say for sure who used the tools.

Fossil that changed everything

Between 2019 and 2021, a team working in Koobi Fora, on the eastern edge of Lake Turkana in Kenya, uncovered a partial skeleton of P. boisei.

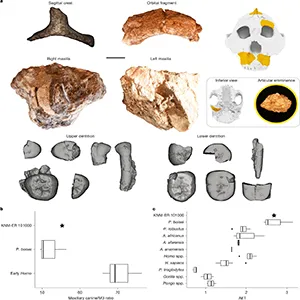

The fossilized remains included cranial fragments, teeth and, most importantly, a well-preserved set of hand and foot bones.

“This is the first time we can confidently link Paranthropus boisei to specific hand and foot bones,” said Carrie S. Mongle, a paleoanthropologist and assistant professor of anthropology at Stony Brook University, who led the study.

“The hand shows it could form precision grips similar to ours, while also retaining powerful grasping capabilities more like those of gorillas, and the foot is unquestionably adapted to walking upright on two legs.”

Altering the story of early tool use

For years, most scientists assumed that only early Homo species made and used tools. This assumption helped separate Homo from other hominins like Paranthropus – at least in terms of behavior. But the new discovery changes that idea.

“There has been a long controversy about whether or not this species made and used stone tools,” said study co-author Matt Tocheri. “This fossil evidence effectively ends that debate.”

The hands of P. boisei were built to grab, hold, and manipulate objects. They had the proportions to use tools just as well as early humans did.

However, the researchers noted that the wrist still lacked some of the specialized features that show up in later humans and Neanderthals. So, while they could use tools, these early hominins may not have used them as often or as precisely.

Built for climbing and eating plants

The team also found that Paranthropus boisei had evolved powerful grasping strength that resembled that found in modern gorillas.

“It [P. boisei] has converged on gorilla morphology in ways that are consistent with obtaining and processing tougher plant foods with its hands, and these powerful grasping abilities would also have been quite useful for climbing,” said study co-author Caley Orr.

Ancient hominin diversity

The research highlights how diverse early hominins were. Some, like early Homo, leaned into tool-making. Others, like Paranthropus, developed strong jaws and hands for grinding and grasping.

The mix of strategies suggests that early hominins were spreading out into different environments and filling different ecological roles.

Some survived by using tools to get meat or break bones. Others might have thrived by processing plants, climbing trees, and doing things their own way.

“This discovery helps us understand a lot more about Paranthropus boisei, especially how its hand shared similarities with members of our own genus, Homo, while evolving its own capabilities,” said Orr.

Paranthropus boisei spawns a new era

Digging up fossils like this takes more than just scientists in the field. It takes time, care, and help from the local community. The excavation at Koobi Fora was a major team effort.

“It took a huge amount of time to carefully remove the sediments that ultimately revealed these amazing fossils,” said Cyprian Nyete, who directed the fieldwork.

Louise Leakey’s team was responsible for recovering the fossils.

“Overall, this discovery is a great example of how much we can achieve when we undertake long-term fieldwork that involves strong collaborations between researchers from around the world and the local communities that live in the places where hominin fossils are preserved,” Leakey enthused.

“It is definitely an exciting new era in paleoanthropology, which has changed and grown so much since my grandparents discovered the first skull of Paranthropus boisei at Olduvai and my parents first began to focus their research on the fossil-rich Turkana Basin in Kenya.”

The full study was published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–