Earth is sprinkling the Moon with water and other life ingredients

The Moon looks dry and lifeless, yet it may hold a long-term archive of Earth’s atmosphere. New research suggests that tiny particles from Earth’s atmosphere have been hitching rides on the solar wind, finding their way into the Moon’s soil.

These particles may stockpile water, nitrogen, and other life-supporting ingredients.

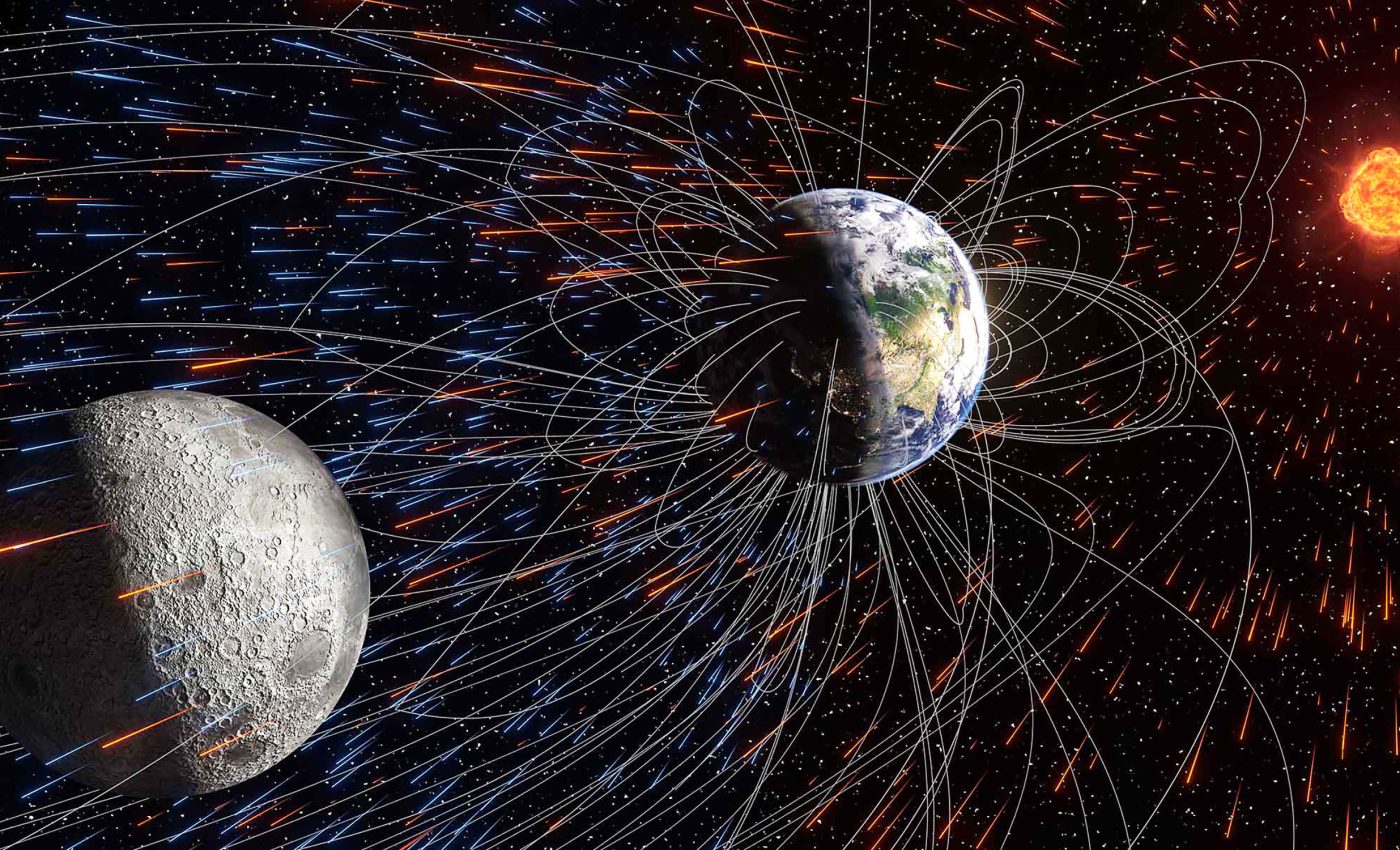

Even more intriguing, the study argues that Earth’s magnetic field – long assumed to act like a shield – may actually help guide some of those particles into space and toward the Moon.

The research, led by experts at the University of Rochester, reframes a decades-old puzzle: why lunar samples contain more of certain volatile elements than the Sun’s particle stream could plausibly supply.

“By combining data from particles preserved in lunar soil with computational modeling, we can trace the history of Earth’s atmosphere and its magnetic field,” said study co-author and astrophysicist Eric Blackman.

Particles from Earth on the Moon

We’ve had a laboratory window into lunar soil ever since the Apollo missions ferried samples home in the 1970s. Those regolith grains carry a cocktail of volatiles – water, carbon dioxide, helium, argon, and nitrogen – that scientists have picked apart grain by grain.

Some of that inventory clearly comes from the solar wind bombarding the surface. But the amounts, especially of nitrogen, don’t add up if the Sun is the only source.

Back in 2005, a team from the University of Tokyo floated a provocative answer: perhaps a portion of those volatiles came from Earth’s atmosphere itself, but only in the deep past, before our planet had a global magnetic field.

The logic was straightforward: if a magnetic shield keeps charged particles from streaming off into space, then Earth’s atmosphere shouldn’t easily leak to the Moon once that field is established.

The new study flips that assumption. It shows there is a pathway for atmospheric particles to escape even with a strong magnetic field and that the field can actually help shepherd those particles along.

Earth’s atmosphere sheds particles

To test the competing ideas, the experts turned to advanced simulations. They modeled two end-member scenarios: an “early Earth” without a global magnetic field in an era of stronger solar wind, and a “modern Earth” with a robust field under gentler solar conditions.

Then, they asked a simple question: under which conditions do you deliver the kinds and amounts of particles seen in Apollo samples to the Moon?

Counterintuitively, the “modern Earth” setup did the better job. In that picture, solar wind ions slam into the fringes of Earth’s atmosphere and knock loose neutral and charged particles.

Rather than acting as a hard shield, the magnetic field’s lines of force act more like rails: they guide charged particles along arcing paths that can extend tens of thousands of kilometers into space.

Some of those magnetic field lines thread outward far enough that liberated atmospheric particles can be shepherded toward the Moon’s orbit and, over time, sprinkled onto its surface.

It’s not a firehose. It’s a slow, steady drizzle, playing out over billions of years.

Lunar archive of Earth’s atmosphere

If Earth has been faintly dusting the Moon all this time, the implications are interesting. The regolith becomes a long-term archive of Earth’s atmosphere.

Layer upon layer of trapped particles preserve a geochemical diary of how the air above our oceans changed over time.

That record reflects shifting continents, erupting volcanoes, evolving life, and, eventually, human industrialization.

That archive could be scientifically priceless. Instead of relying solely on Earth’s often jumbled rock record, researchers could “read” buried lunar layers for clues to ancient climate swings, ocean chemistry, or the timing of big atmospheric transitions.

Because the Moon lacks weather, plate tectonics, and life to churn and erase its surface, it’s a remarkably stable vault.

And for explorers, the practical payoff is just as compelling. A slow accumulation of Earth-sourced volatiles, especially water and nitrogen, adds to the Moon’s in-situ resource potential.

If future crews can extract and purify those ingredients efficiently, they could make air, water, and fertilizer on site, reducing the need for costly resupply from Earth. Even modest local stocks could tip the economics of a lunar outpost from barely feasible to sustainable.

Implications beyond Earth

The team’s approach also opens a comparative window onto other worlds. Mars, for instance, once had a global magnetic field and a thicker atmosphere. Today, it has neither.

Understanding how magnetic geometry, solar wind strength, and atmospheric chemistry knit together over time can sharpen our answers to big questions: When did Mars become arid? How fast did it lose air? Under what conditions do planets keep volatile inventories long enough for life to gain a foothold?

“Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars,” noted co-author Shubhonkar Paramanick.

Looking across different epochs, he said, helps reveal how these coupled processes shape planetary habitability.

Earth, the Moon, and life particles

Stepping back, the findings don’t deny that the solar wind implants volatiles in the Moon. They rewrite the second act of the story. Earth isn’t a bystander.

Given the right magnetic geometry and solar conditions, our planet can leak trace atmospheric particles along magnetic superhighways that arc out toward the Moon.

The effect is subtle, cumulative, and ancient – exactly the kind of slow physics that leaves its mark over geologic timescales.

The next moves are obvious and exciting. Researchers want targeted sampling of shadowed and sunlit regolith at different depths and latitudes.

They also plan isotopic “fingerprinting” to separate Earth-sourced volatiles from solar and cometary material. Future missions would explicitly treat the Moon as both a resource and a record.

The Moon has been reflecting sunlight for as long as humans have gazed up at it. Now it turns out it has been reflecting us, too – quietly collecting the faintest traces of our air, one particle at a time, for billions of years.

The study was published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–