Enormous 68-million-year-old egg nicknamed 'The Thing' is excavated in Antarctica

About 68-million-years ago, during the Late Cretaceous, a giant fossil egg was laid in Antarctica. The excavated remains reveal that a huge marine reptile laid eggs instead of giving birth to live offspring, as scientists originally assumed.

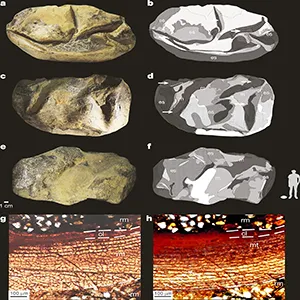

Nicknamed “The Thing,” the fossil egg measures about 11-inches long and 8-inches wide and was uncovered on Seymour Island.

Those measurements make it the largest soft-shelled egg ever found and the second largest egg from any animal.

Fossil egg in an unlikely place

At first the fossil did not look like an egg at all. It was a leathery, folded object buried in Antarctic sediment and it reminded researchers of a deflated bag.

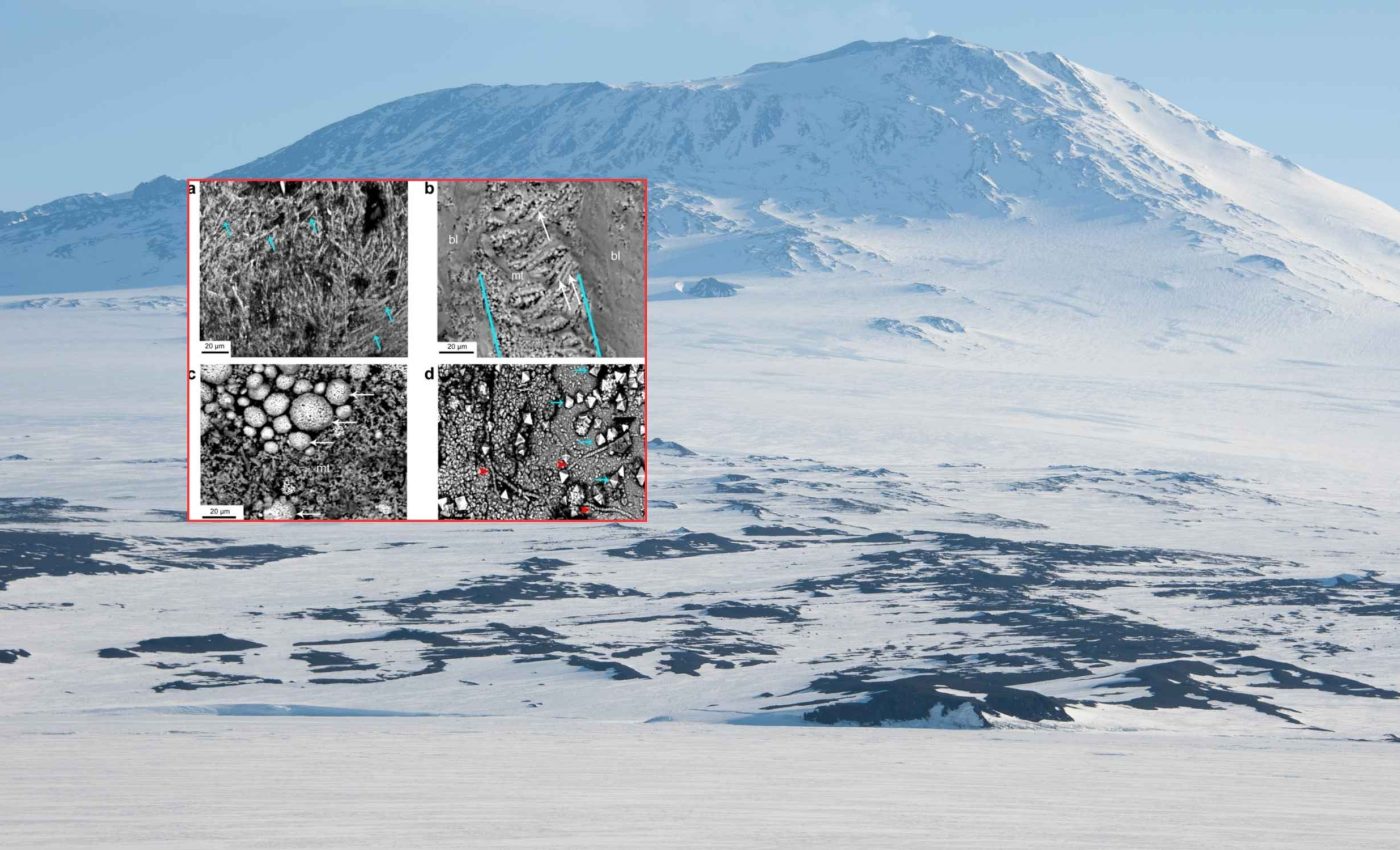

Under a microscope, thin sections of the fossil revealed a delicate wall only a fraction of a millimeter thick.

That wall lacked obvious pores and instead showed stacked layers, giving it the texture of a modern lizard or snake egg rather than the thick, chalky shells many people picture for dinosaur eggs.

The work was led by Lucas Legendre, a paleontologist at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on fossil eggs and how reptile reproduction evolved over deep time.

Eventually the team assigned the formal name Antarcticoolithus bradyi, the official fossil label for this unusual egg, to the specimen.

The slow, careful reconstruction of its shape showed that the shell had collapsed after hatching, which is why the fossil looks like an empty sack instead of a neatly rounded egg.

How giant reptiles reproduced

Before this discovery, large marine reptiles such as mosasaurs, huge lizards that hunted in ancient oceans, were widely thought to give birth to live young.

Earlier work on tiny mosasaur skulls from open ocean rocks suggested that some of these lizards gave birth far from shore instead of coming onto beaches to lay eggs.

The Antarctic egg points to a different strategy. Its thin, flexible shell suggests that at least one marine reptile laid soft-shelled eggs in the water, with the young hatching almost at once rather than sitting in a nest for weeks.

The egg came from an animal comparable in size to a large dinosaur, yet its structure showed none of the typical features seen in dinosaur eggs.

It was also noted for its unusual combination of size and form, which set it apart from any known fossil egg type.

Across reptiles as a whole, live offspring-bearing called viviparity, in which mothers retain embryos until birth, has evolved many times but rarely leaves clear fossils.

This Antarctic egg hints that some marine reptiles may have used a mixed approach, with mothers carrying young almost to term and then releasing an egg that hatched quickly in the water.

Who laid this fossil egg?

Near the egg, researchers found bones from Kaikaifilu hervei, a large species of mosasaur known from the same rock formation on Seymour Island.

A detailed description of this animal shows that it reached about 33 feet in length, making it the biggest known top predator from Antarctic seas of that time.

The egg’s estimated parent length of more than 23 feet, based on comparisons with 259 modern reptile species, fits comfortably within that size range.

That match, along with the closeness of the fossils, makes Kaikaifilu a strong candidate as the egg layer, even if the link cannot yet be proven.

The area also preserves small bones from young mosasaurs and from plesiosaurs, long necked marine reptiles with flippers, suggesting that the region functioned as a nursery.

In such a setting, freshly laid eggs that hatched almost at once would have released mobile babies directly into sheltered coastal waters.

Soft-shells in the deep past

For decades, almost all known fossil eggs from dinosaurs and other ancient reptiles had thick, mineral-rich shells.

That record made scientists think that hard shells were the ancestral pattern, and that softer eggs were rare exceptions.

That view has started to change. An independent analysis that examined eggs from the plant-eating dinosaurs Protoceratops and Mussaurus found that their shells were leathery and flexible, not rigid like a bird-egg.

The research team behind that work concluded that soft-shells were likely present in the earliest dinosaurs and that rigid shells evolved several times in separate lineages.

A museum report for the public explained that these early dinosaur eggs probably resembled turtle eggs, with leathery coverings that could be buried in soil or sand.

The Antarctic egg slots into this emerging picture, extending the reach of soft-shells into giant marine reptiles living near the poles.

Lessons from Antarcticoolithus bradyi

Soft-eggs almost never survive long enough to fossilize because bacteria and scavengers destroy them quickly.

The preservation of this one suggests that the sedimentary environment, layers of mud and sand laid down in a shallow sea, rapidly buried the egg and shielded it from decay.

Antarctica’s climate was warmer at the time, with ice-free coasts and productive seas, even though the region still sat within the polar circle.

Those conditions, combined with steady sediment buildup, turned parts of the seafloor around Seymour Island into natural vaults for delicate remains.

Well-preserved embryos of Protoceratops from Mongolia show how entire nests can sometimes be locked in stone.

In a similar way, the Antarctic egg and nearby juvenile marine reptiles offer a snapshot of how life began for some of the largest predators in southern oceans.

Each new find could tighten the connection between egg type, nesting behavior, and environment, revealing how life cycles adapted to cold, seasonal light near the ancient South Pole.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–