Every major city in the U.S. is sinking, and some are dropping faster than others

A striking new study has found that all of the 28 largest cities in the United States is sinking to some extent, with certain areas within cities dropping faster than others.

The research sheds light not only on the coastal cities already grappling with sea-level rise, but also on inland metro areas where land subsidence poses an overlooked threat to infrastructure.

The ground can’t keep up

Study lead author Leonard Ohenhen, a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia Climate School’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, elaborated on the findings.

“As cities continue to grow, we will see more cities expand into subsiding regions. Over time, this subsidence can produce stresses on infrastructure that will go past their safety limit.”

Cities like Jakarta, Venice, and New Orleans are already known for sinking under their own weight or rising seas. This new study takes a broader look at the United States, using highly detailed data.

Millions living on sinking ground

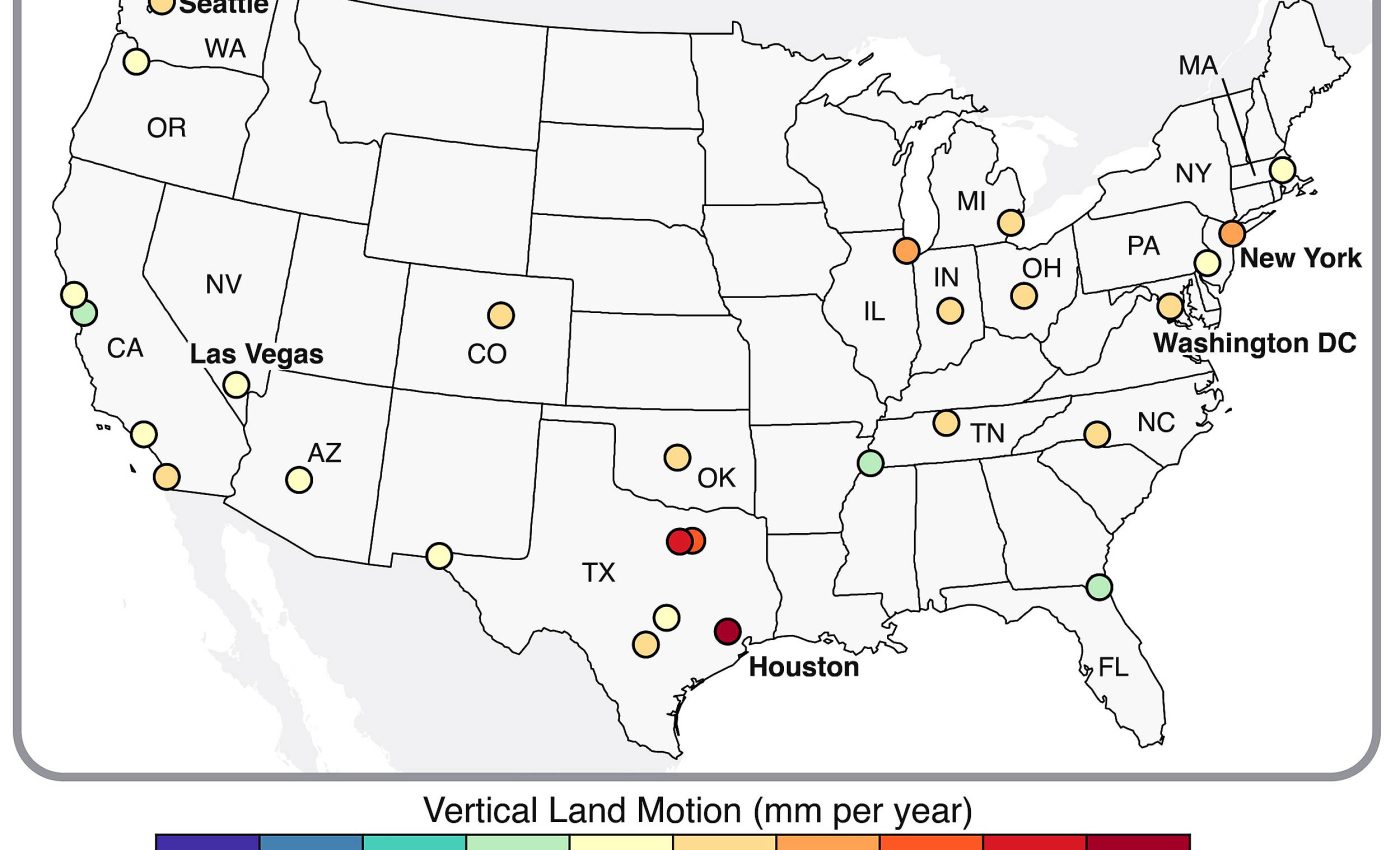

In all U.S. cities with populations over 600,000, the researchers used recent satellite data to map vertical land movement with millimeter precision, using grids just 28 meters (about 90 feet) wide.

The experts found that in 25 of the 28 cities, at least two-thirds of the land area is sinking. In total, about 34 million Americans live on these subsiding lands.

Houston emerged as the fastest-sinking major city. More than 40% of its area is sinking by over 5 millimeters (about one-fifth of an inch) per year, with 12% subsiding at twice that rate. In some areas, the ground is dropping as much as 5 centimeters (2 inches) per year.

Fort Worth and Dallas also show high rates, while other fast-sinking zones include areas near New York’s LaGuardia Airport, Las Vegas, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco.

Texas faces added risks

In most cases, the primary driver is massive groundwater extraction. Pumping water from underground aquifers causes the fine-grained sediments to compact. This collapse of pore spaces leads to sinking land above.

In Texas, the issue is compounded by oil and gas extraction, the study notes. Climate change-induced droughts, combined with continued population growth and water use, are likely to intensify these effects in the coming years.

Ice age is still shaping land

Humans are not responsible for all of the sinking ground. Some subsidence is the result of natural processes dating back thousands of years.

The study highlights lingering effects from the last ice age. The immense weight of ancient ice sheets caused the surrounding land to bulge upward, like air squeezed in a balloon.

Today, long after the ice has melted, some of these bulges are still slowly sinking. Cities affected include New York, Philadelphia, Indianapolis, Nashville, Chicago, Denver, and Portland.

Even the sheer weight of buildings may be playing a role. A 2023 study suggested that the enormous mass of New York City’s one million-plus buildings is exerting pressure that may contribute to ongoing subsidence.

Similarly, a separate study in the Miami area found that some buildings are sinking partly due to subsurface disruptions caused by nearby construction projects.

America’s sinking hotspots

Eight major cities – New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Houston, Philadelphia, San Antonio, and Dallas – account for over 60% of the people living on sinking land.

Since 2000, these cities have collectively experienced over 90 major floods, some likely worsened by sinking ground.

An especially worrisome finding involves “differential motion,” where some neighborhoods within a city are sinking faster or slower than others, or even rising due to rapid aquifer recharge near rivers or water sources.

Thousands of buildings at risk

While overall land movement might be slow, uneven changes create stresses that can tilt buildings and damage infrastructure.

The study estimates that about 1% of total land area in the 28 cities lies in zones where differential motion could significantly affect roads, railways, or buildings.

These zones are often in densely populated urban cores, affecting roughly 29,000 buildings. San Antonio faces the highest risk, with about one in 45 buildings potentially affected – followed by Austin, Fort Worth, and Memphis.

How cities can respond

Though the scale of the issue is daunting, the authors stress that solutions are within reach. For flood-prone areas, land raising, better drainage, and green infrastructure like artificial wetlands help manage excess water.

For cities facing risks from tilting, solutions might include retrofitting buildings, updating building codes to account for ground movement, and limiting new development in the most affected zones.

“As opposed to just saying it’s a problem, we can respond, address, mitigate, adapt,” Ohenhen said. “We have to move to solutions.”

An earlier study of 225 U.S. building collapses from 1989 to 2000 found subsidence directly caused just 2% of cases. However, in 30% of cases, the cause was unknown – suggesting ground sinking may play a larger, hidden role, the study says.

Acting before the ground sinks

With detailed maps of sinking zones now available, cities have a chance to integrate this knowledge into urban planning, infrastructure design, and disaster preparedness.

As the pressures of climate change, population growth, and resource use continue to rise, understanding the ground beneath our feet may be just as critical as managing the forces above.

The new research serves as both a warning and a call to action, offering tools and knowledge that cities can use to protect residents and infrastructure before problems escalate further.

The study is published in the journal Nature Cities.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–