Global crop yield declines will not discriminate between rich and poor nations

As Earth warms, crops across continents are yielding less – an alarming trend traced by a new global dataset on food and climate.

The report was released on the UNDP Human Climate Horizons platform and built in collaboration with experts at the Climate Impact Lab.

The team estimates that each additional degree Celsius of global warming cuts the global food supply by about 120 calories per person per day.

“If the climate warms by 3 degrees, that’s basically like everyone on the planet giving up breakfast,” said senior author Solomon Hsiang, a professor of environmental social sciences at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

Crop yield climate crisis

The implications stretch far beyond farm fields. More than 800 million people already experience periods without enough to eat. Shrinking yields amplify that pressure, with ripple effects on income, stability, and health.

“Climate change is not just an environmental challenge – it is a profound development crisis,” said Pedro Conceição, the director of UNDP’s Human Development Report Office.

“High agricultural yields are important not just for food security, they also sustain livelihoods and open pathways for economic diversification and prosperity. Threats to agricultural yields are threats to human development today and in the future.”

Emissions cuts change the story

The dataset highlights how strongly policy choices influence outcomes. If the world races toward net-zero emissions, global crop yields are projected to fall by about 11 percent.

If emissions continue to climb, the decline roughly doubles to 24 percent. That pattern holds across rich and poor countries alike: mitigation doesn’t eliminate losses, but it halves them.

Mapping global crop risks

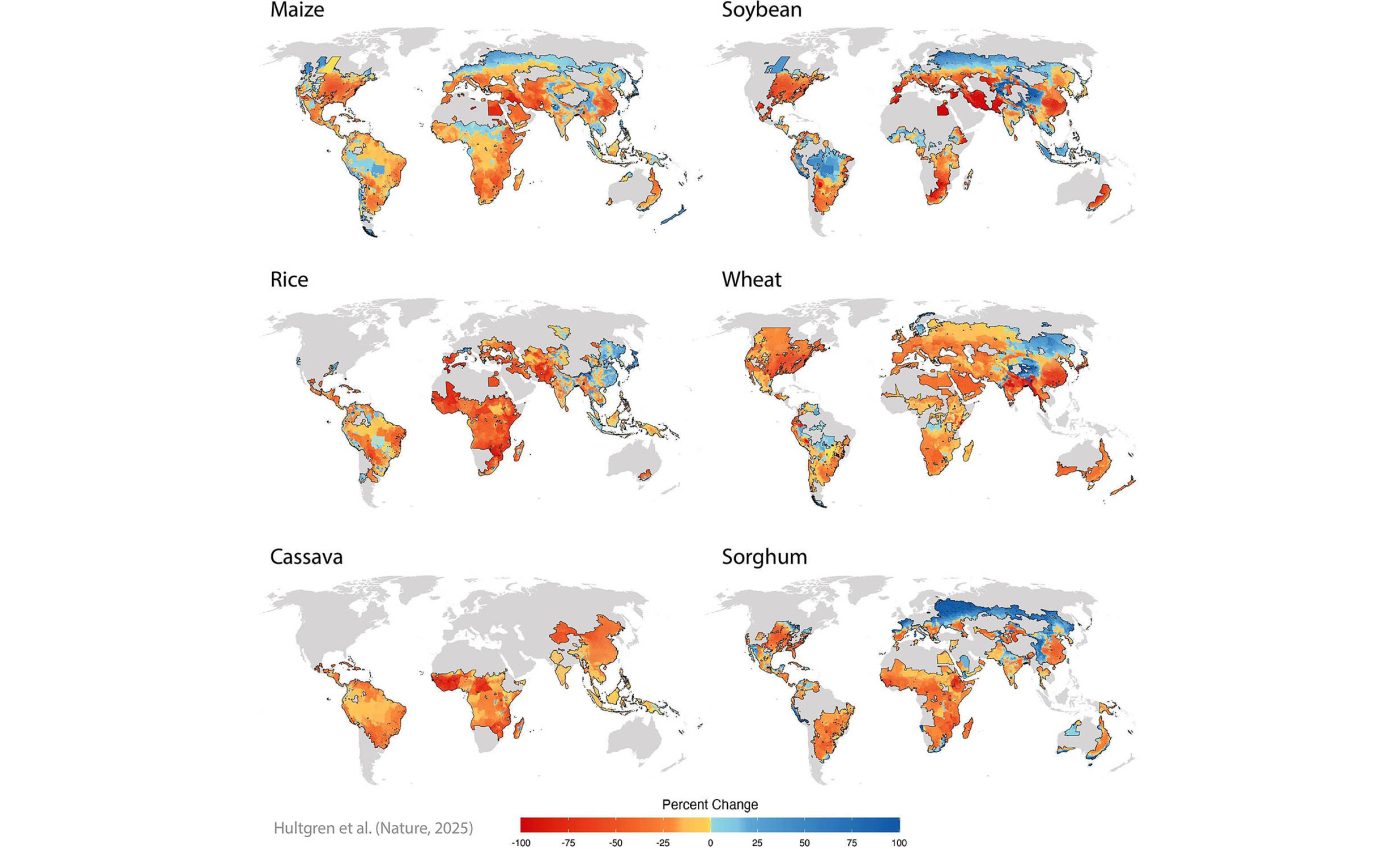

To move from global averages to actionable insights, the team linked climate variables to yields for six staple crops: corn, rice, wheat, soy, cassava, and sorghum.

The experts projected outcomes across three time windows – near term (2020–2039), mid-century (2040–2059), and century’s end (2080–2099).

The Human Climate Horizons release provides subnational detail for more than 19,000 regions across over 100 countries, showing where risks concentrate and where adaptation can help.

Even with farmer-level adjustments – such as switching varieties, shifting planting dates, and changing fertilizer strategies – only about one-third of end-century climate losses are offset if emissions remain high.

Except for rice, the probability of yield declines by 2100 ranges from roughly 70 to 90 percent for each crop.

Unequal climate costs emerge

The analysis reveals a harsh asymmetry. Many of the world’s poorest nations face steep agricultural losses.

By late century, high warming could cut median national yields by about 25 to 30 percent, striking sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia hardest.

Cassava – crucial to caloric intake for millions of low-income households – is a standout vulnerability.

Food systems in these regions also have smaller financial cushions and weaker infrastructure. That combination leaves them highly exposed when yield shocks hit, raising the risk of broader crises.

Crop powerhouses under threat

Major exporters don’t escape the heat. Under severe warming, the United States and other heavyweights in wheat and soy show some of the largest projected drops – up to 40 percent.

Those declines could inject new volatility into global prices, trade flows, and political stability.

“Places in the Midwest that are really well suited for present day corn and soybean production just get hammered under a high warming future,” said study lead author Andrew Hultgren.

“You do start to wonder if the Corn Belt is going to be the Corn Belt in the future.”

Forecasting a safer crop harvest

The Climate Impact Lab is working with governments to steer limited adaptation funding where it can do the most good.

A central hurdle is basic information: many farmers still lack reliable, location-specific weather intelligence. That is starting to change.

The Human-Centered Weather Forecasts Initiative at the University of Chicago uses AI to craft forecast products around the decisions farmers actually face.

This summer, the team partnered with the Indian government to give 38 million farmers early, actionable guidance on monsoon timing.

The project’s co-director, Amir Jina, explained that once the rain starts, it can be too late to make big important decisions, like changing a crop, planting more land, or forgoing the farming season and getting a job in the city instead.

“By providing an accurate forecast around a month in advance, farmers were able to align their decisions with the coming weather and make better choices,” said Jina.

Urgency before global talks

The takeaway for negotiators and national planners is clear: mitigation and adaptation are both essential. Deep emissions cuts sharply reduce the scale of losses.

Targeted investments – including seed systems, heat- and drought-tolerant varieties, irrigation, and farmer finance – can blunt impacts even further.

With a high-resolution, country-by-country picture, governments can pinpoint the most climate-exposed regions and crops yields. They can stress-test food systems against multiple futures and make choices that keep breakfast on the table.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–