Severity of future heatwaves will likely overwhelm hospitals

Heatwaves like the one in 2003 could cause tens of thousands of deaths in a single week if they struck today’s Europe. That weekly toll, projected in a new study, would rival the deadliest weeks of COVID-19 on the continent.

Global average temperatures are already about 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) above pre-industrial levels. That extra heat means the kind of summer that shocked Europe in 2003 now sits on top of a much hotter baseline atmosphere.

Yesterday’s heatwaves are deadlier today

The work was led by Christopher W. Callahan, an assistant professor at Indiana University. He is a climate scientist whose research tracks how extreme events affect human health and economies, especially in regions that live with high temperatures.

The researchers asked what would happen if the exact same weather patterns struck in climates that are warmer by different amounts.

They explained that when those systems unfold in a hotter world, the heat becomes more intense and the number of deaths increases.

Global warming changes the background conditions everywhere, and the biggest dangers appear when that added heat coincides with unusual weather patterns. Climate scientists call these compound extremes – events where multiple hazards hit together.

How to study heatwaves

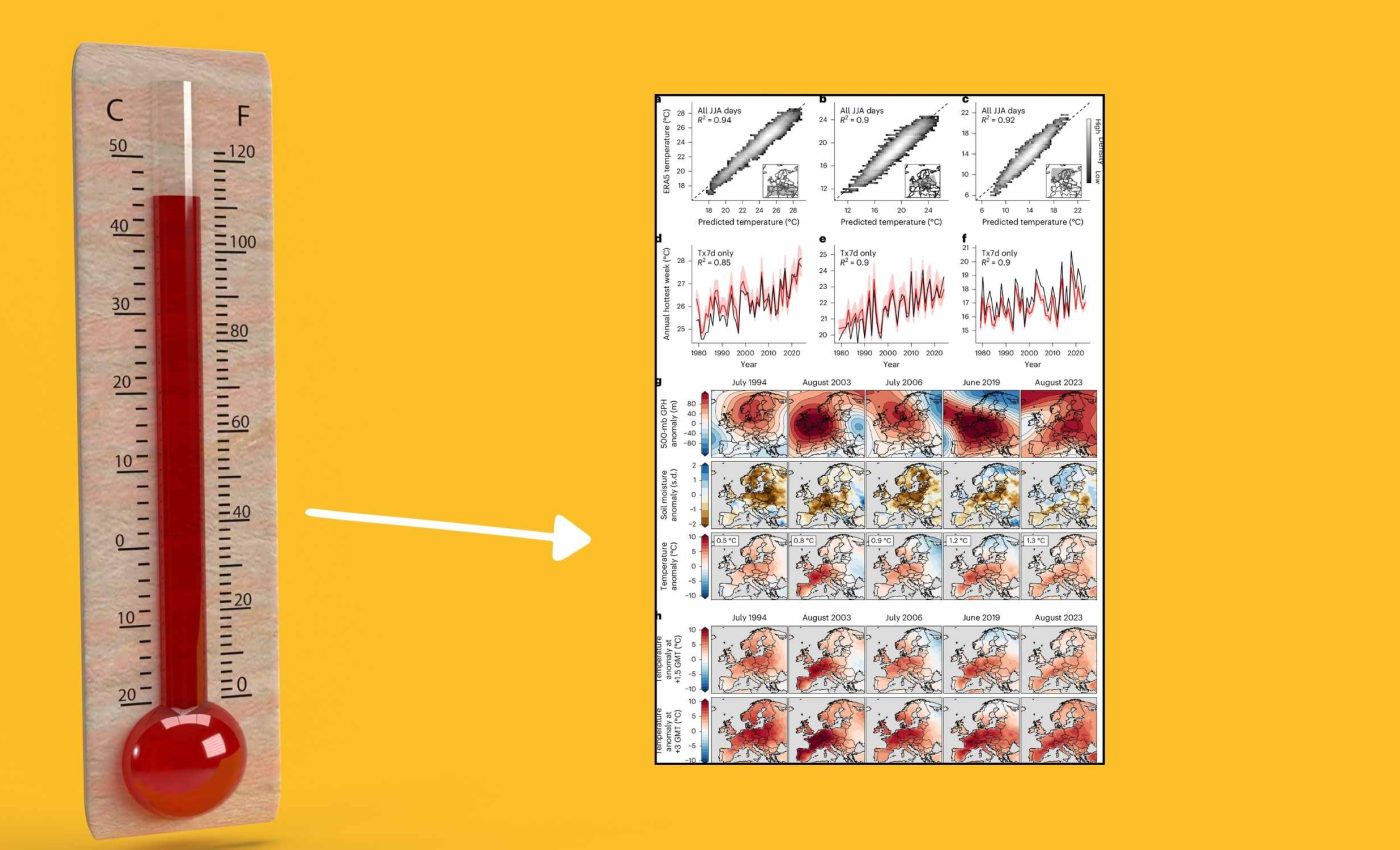

Instead of guessing at a generic future, the team took five real European heatwaves from 1994, 2003, 2006, 2019, and 2023.

They then used artificial intelligence trained on climate models to see how those weather setups would play out at different levels of global warming.

To connect temperature to health, the researchers studied weekly death records from 924 regions across Europe between 2015 and 2019.

They built exposure response curves, which are statistical tools that relate temperature levels to changes in death rates.

Replaying the August 2003 weather pattern in today’s climate produced an estimate of about 17,800 deaths across Europe in a single week. Those are excess deaths – deaths above the normal weekly number.

At at about 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius) of additional warming a similar event could kill 32,000 people.

By pairing climate models with weather maps, the artificial intelligence system learned how pressure patterns, soil dryness, and wind flows translate into surface temperatures.

That let the team ask “what if” questions, such as replaying the 1994 heatwave in a world where temperature is higher.

Why extreme heat is so deadly

The team saw risk jump once days reached about 86 degrees Fahrenheit in even the hottest parts of Europe. That corresponds to roughly 30 degrees Celsius, a level where heat starts overwhelming the body’s ability to stay cool.

Recent summers show that these are not abstract numbers. In 2022, extreme heat was linked to about 61,700 deaths across Europe, according to researchers who examined daily mortality records from 35 countries.

In 2024, another team estimated around 62,800 heat-related deaths across the continent, roughly one quarter more than in 2023. They used a database of 654 regions in 32 countries to show how heat hits different populations.

When air and surfaces stay hot through both day and night, the body cannot shed stored heat, and core temperature rises.

That strain can trigger strokes, heart failure, or dangerous dehydration, especially when people cannot access cool indoor spaces.

Adaptation limits and hospital strain

The study suggests that adaptation keeps following trends, so hotter summers would avoid about one in ten deaths that extreme heat would otherwise cause. Adaptation here means practical moves like warning systems and cooling centers.

Extreme heat also threatens to jam hospitals and clinics, because heart attacks, breathing problems, and kidney failure all spike on very hot days.

Heat deaths are especially likely among older adults and people with chronic health conditions, who may struggle to cool their homes or reach care.

The authors warn that planning for extreme heat needs to treat these weeks like a public health emergency, not just uncomfortable weather.

Heatwaves also worsen indirect problems, such as power outages that shut down air conditioning, and water shortages that limit basic hygiene.

The authors note that outdoor workers, like farm laborers and construction crews, face exposure because their jobs cannot shift away from the hottest hours.

Future lessons from past heatwaves

A modeling analysis finds that if global warming reaches about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius), heat could cause 160 to 170 deaths per million people yearly.

If warming climbs beyond about 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius), that study projects 467 heat related deaths per million people yearly, with the heaviest burden in southern regions.

Europe’s population is aging, cities tend to trap heat, and many homes lack strong cooling. Those factors mean the continent could see rising heat deaths, even if winters become slightly milder, because the hottest weeks bring very concentrated danger.

The authors highlight practical steps, including cooling plans for hospitals, outreach to isolated people, and city designs that add shade.

With strong cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, those moves would make these extreme spikes in heat deaths far less likely.

European governments are drafting climate plans that aim to limit warming near about 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius), but the study shows deadly heat weeks remain possible.

Stronger local adaptation plans, like keeping hospitals supplied and neighborhoods shaded, will help decide whether those scenarios stay on paper or become reality.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–