Hera spacecraft takes planetary defense to the next level as it approaches Didymos asteroids

About a year ago, a spacecraft named Hera took off with a huge task: help us figure out how to stop an asteroid from hitting Earth. It’s now roughly halfway to the Didymos asteroid system and, so far, the journey’s going better than planned.

The purpose of this mission is to see if we can actually change the path of a dangerous asteroid. Hera will head to the same place where, in 2022, NASA crashed a spacecraft into a small asteroid called Dimorphos.

That was part of a test called DART, and it worked – the impact nudged Dimorphos slightly out of its orbit around a larger asteroid, Didymos.

Now, Hera will return to measure what changed and to help us learn how to do this kind of thing on purpose – if we ever need to save the planet from an impact.

Hera’s busy first year in space

Hera had a strong start. After lifting off on October 7, 2024, it fired its engine and flew straight toward Mars.

It used the Red Planet’s gravity in March 2025 to curve its path toward Didymos, which helped save fuel and speed up the trip.

The team used this Mars flyby to test out Hera’s science tools by getting a close-up look at a known planet.

After that, they turned the spacecraft’s main camera toward faint asteroids in deep space to practice for its future encounter with Didymos.

Lisa Savarieau is a Hera spacecraft operations engineer at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Germany.

“Hera is the first interplanetary mission for some of the younger members of the team, and I have been impressed by their ability to prioritise, overcome challenges, and be creative, given the mission’s very busy schedule,” said Savarieau.

Hera’s Didymos maneuver plan

Sylvain Lodiot, head of Outer Solar System and Planetary Defence Missions Operations at ESA, noted that the spacecraft’s performance gave the team enough confidence to try something bold.

“The reliability of the propulsion system, in particular, has enabled the team to design a new, more aggressive maneuver plan that involves ‘braking’ later and harder during the approach to Didymos,” said Lodiot.

“This will allow Hera to arrive at the asteroids a month earlier than we had initially planned.” Hera will now arrive in November 2026, instead of December.

Hera spacecraft can steer itself

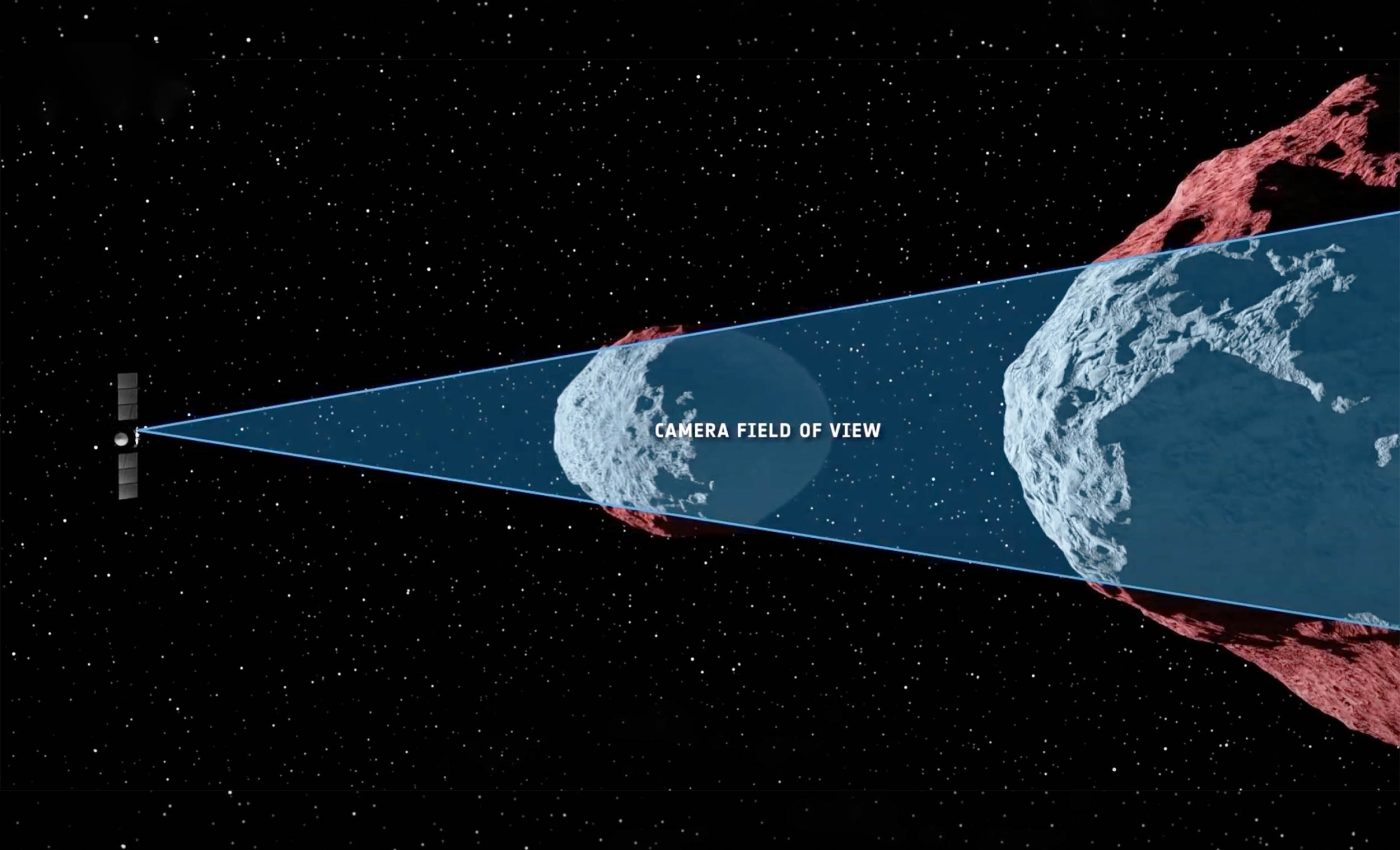

Flying near asteroids isn’t easy. There’s no GPS in space, and when you’re hundreds of millions of miles from Earth, radio commands take too long to be useful in real time.

That’s why Hera is equipped with a new self-driving system that lets it navigate on its own.

This system uses data from several sensors and keeps the target asteroid within view of Hera’s camera. That’s not simple. Dimorphos is only about 525 feet (160 meters) wide and still pretty much unexplored.

To make sure everything works, engineers tested this autonomous system, both in space and on the ground. During Hera’s launch and Mars flyby, it was tested on real targets.

The ground testing happened at OHB in Bremen, Germany, using the most complex navigation simulation ever done for a European spacecraft.

Hera, Didymos, and CubeSats

Hera isn’t making this journey alone. There will be two mini-spacecraft called CubeSats tucked inside – Milani and Juventas.

They’re about the size of carry-on suitcases, and they’ll be released near the asteroid system to carry out their own investigations.

During the cruise, Hera’s team regularly wakes up these CubeSats to check that they’re still functioning. Data and commands travel between them and Earth through Hera’s communication systems, using what’s called an Inter Satellite Link.

On Earth, a new control center has been built in Belgium at ESA’s European Space Security and Education Centre (ESEC). It will connect teams from Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and France, each in charge of different parts of the CubeSat missions.

Milani will be operated by Tyvak in Italy, and Juventas by GomSpace in Luxembourg. The French space agency CNES is helping plan the missions.

The challenge? Tiny spacecraft in a place with almost no gravity. Even sunlight can push them off course.

The mission is the first to try and control three separate spacecraft operating in such a delicate environment.

The teams have put together careful plans to avoid crashes – either with each other or the asteroids.

What’s happening with Hera now

Right now, Hera is out of contact with Earth. That’s because it’s behind the Sun from our point of view, which blocks radio signals. Communication will resume around October 24.

In November, the spacecraft will reach its farthest point from the Sun. Engineers will need to keep the spacecraft warm enough to function, even though it will be getting less solar power.

Teams are also testing communication links with antennas from the Japanese space agency (JAXA). These antennas could step in if help is ever needed to send data or commands.

The next big step will come in February 2026, when Hera will make a deep-space maneuver to line itself up for its arrival at Didymos.

“Hera’s first year in space has been incredibly successful and action packed,” said Hera mission manager Ian Carnelli.

“The spacecraft is in excellent health, the teams on Earth are putting in great effort to prepare for arrival at Didymos, and we are looking forward to the day that Hera begins the next phase of humankind’s shared mission to learn how to reliably protect our planet from dangerous asteroids.”

Information for this article came from an ESA media release.

Image credit: JAXA and ESA

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–