Human activities have literally changed the way Earth spins, according to scientists

Most people don’t spend much time thinking about human-built dams, but they play a huge role on Earth. They block rivers, form lakes, and send electricity to nearby towns and cities.

Dams also help people water crops, control floods, and store drinking water. It all feels very practical and sustainable.

But when you step back and look at our planet as a whole, all that water stored behind dams changes things at the macro level.

Each time we trap a river behind a wall of concrete, we are picking up a thin layer of water from the oceans and stacking it into a deep pool on land. Bit by bit, humans have rearranged a noticeable amount of Earth’s water into new locations.

How dams are linked to Earth’s spin

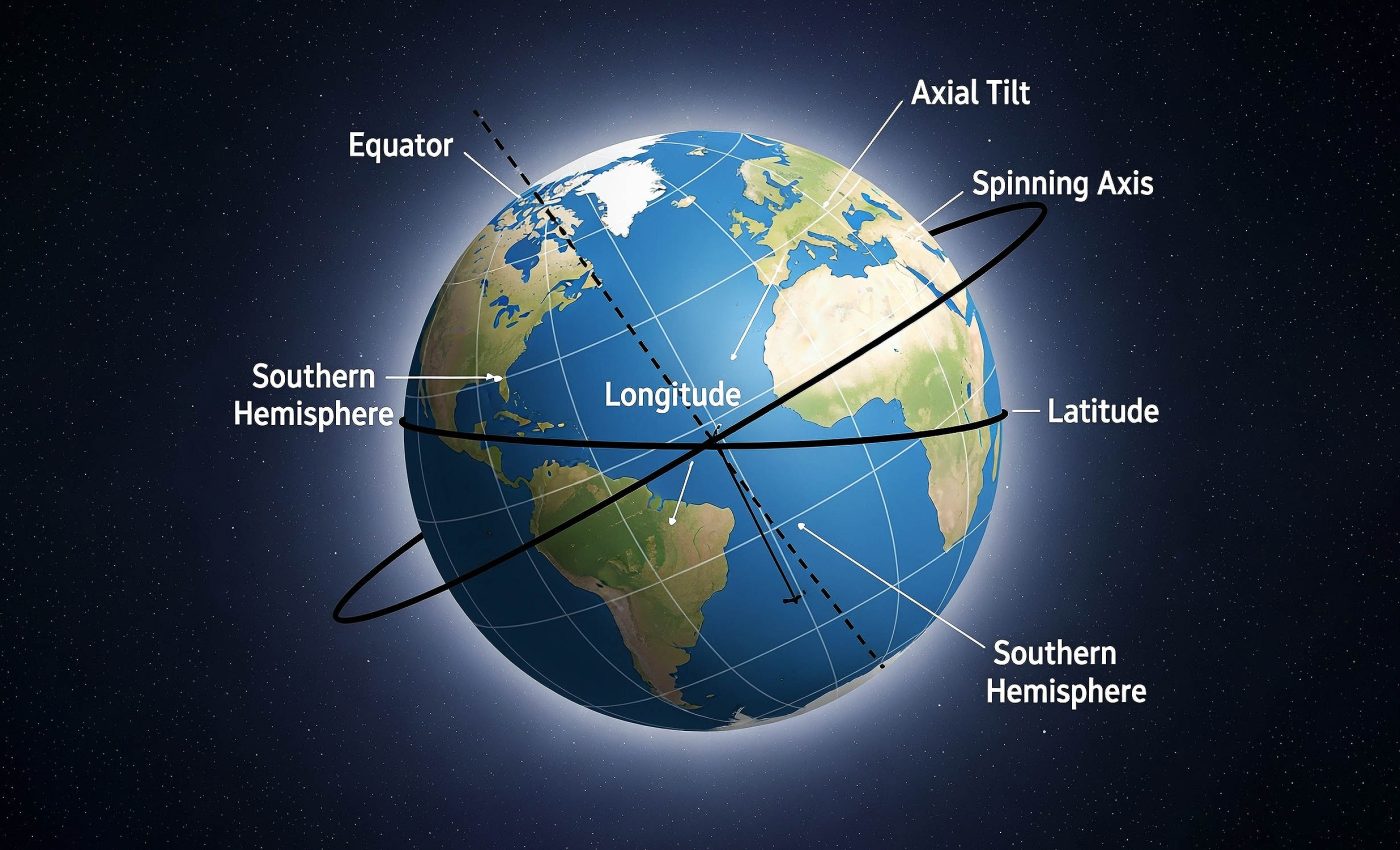

Because Earth is spinning on its axis, that water rearrangement has created an issue.

Shifting where the mass sits on a spinning planet is similar to moving your arms while you spin on a chair: the motion changes in small but measurable ways.

In a recent study from Harvard University, scientists show that building thousands of reservoirs has nudged the positions of the geographic poles by about a meter over the past two centuries.

The effect is tiny in everyday terms, but it reveals just how closely Earth’s rotation is linked to the ways we reshape water on our planet.

Earth’s spin tied to mass

Earth spins once every 24 hours. Spinning objects tend to keep more of their mass around the middle, or equator, because that arrangement makes rotation more stable.

If you gather a lot of mass in one area, you change that balance, and the planet slowly responds by adjusting its outer layers.

When Earth’s entire outer shell – the crust plus the upper mantle – turns slightly relative to the spin axis in space, scientists call it true polar wander.

The axis that Earth spins around keeps pointing in the same direction in space, but the solid surface moves around it a bit. So the physical locations of the North and South Poles drift across Earth’s surface over time.

This motion is different from the wandering of the magnetic poles and from plates sliding around due to plate tectonics.

Rivers turned to reservoirs

Over the last 200 years or so, humans have built over 7,000 dams. Behind the dams, reservoirs store enormous amounts of water on land.

Once that water is stored on land, you’ve effectively moved a huge amount of mass from a thin layer spread over the global ocean to thick “blobs” of mass sitting in certain regions, like western North America, Europe, or Asia.

In some explanations of this work, Earth even plays the role of a spinning “top,” with its orientation reacting to where these blobs end up.

Earth as a spinning ball

To figure out what that trapped water does to the whole planet, the team needed to do more than just count reservoirs. They also needed to know how Earth itself reacts.

For that, they used a standard model of Earth’s interior that describes how dense and how rigid the planet’s layers are at different depths.

With this model, they treated Earth like a spinning, elastic ball. When you put a big load of water in one place, the crust flexes slightly, gravity shifts a bit, and the whole outer shell can reorient by a tiny amount.

Another important part is how the ocean reacts. When you take water out of the oceans to fill reservoirs, sea level falls a little and then readjusts.

The ocean surface always tries to follow the combined pull of gravity and rotation, so it doesn’t just dip uniformly everywhere. Water sloshes around until the ocean finds a new balance.

The scientists included both the direct load of the reservoirs on land and this readjustment of the oceans in their calculations. They even separated these two pieces and showed that both play a significant role in the final effect on the poles.

Measuring the wander

After running their model from 1835 to 2011, they found that building reservoirs caused the geographic pole to move by about 3.7 feet (1.13 meters) along Earth’s surface.

That’s roughly the length of a baseball bat. Most of that motion came during the 20th century, when dam construction grew rapidly around the world, so the main impact lines up with the era of big hydroelectric and water-storage projects.

The direction of that pole motion shifted over time because the main dam-building regions moved. In the earlier period, from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, many of the largest dams were built in North America and Europe.

Storing big lakes of water in those regions subtly moved mass in a way that nudged the North Pole toward a longitude running roughly through Russia and parts of Asia by about 12 inches. After about 1954, massive dam projects expanded quickly in Asia and parts of Africa.

With so many large reservoirs now appearing in new locations, the direction of polar drift turned almost the other way.

This sent the geographic pole on a path toward a longitude that cuts through western North America and over the Pacific Ocean. Over several decades, this created a new trajectory for the slowly wandering pole.

Impact of dams on sea levels

Besides looking at Earth’s spin, the study also took a deeper look at sea level. When scientists talk about sea level, they speak in broad terms, like “sea level is rising by about a few millimeters per year.” But sea level does not rise or fall evenly everywhere.

Changes in mass distribution cause “fingerprints,” or distinct patterns, around the world. Some regions rise more, others less, and a few may even fall.

By pulling water into specific river basins and locking it there, dams have slightly reshaped that pattern. Because those reservoirs pulled so much water out of the oceans, they also masked part of the global sea-level rise caused by melting ice and warming oceans during the 20th century.

“As we trap water behind dams, not only does it remove water from the oceans, thus leading to a global sea level fall, it also distributes mass in a different way around the world,” said Natasha Valencic, a graduate student in Earth and planetary sciences at Harvard and lead author of this study.

“We’re not going to drop into a new ice age, because the pole moved by about a meter in total, but it does have implications for sea level.”

Human-built dams and Earth’s spin

The scientists are careful to point out that this effect is tiny compared with Earth’s size. A move of about three feet (1 meter) over nearly two centuries does not throw the planet off balance in any way that people would feel.

It doesn’t suddenly change the seasons or the length of the day in a way that matters for everyday life. Even so, measuring this small shift helps scientists better understand and correct for other subtle changes in Earth’s system.

What it does show, though, is powerful in a different way. For most of Earth’s history, things like mantle flow, mountain building, and giant ice sheets controlled where mass sat and how the planet spun.

Now, human engineering has become large-scale enough that it leaves a measurable mark on Earth’s rotation and sea-level history.

“Depending on where you place dams and reservoirs, the geometry of sea level rise will change,” Valencic concluded. “That’s another thing we need to consider, because these changes can be pretty large, pretty significant.”

The study gives geophysicists a better way to correct for that “human fingerprint” so they can more accurately interpret modern polar motion and sea-level records, especially when they want to know how fast ice sheets and glaciers are shrinking.

The full study was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–