Discovery reveals human ancestors somehow sailed Earth's oceans over 1 million years ago

Tiny fossils can sometimes spark enormously complicated questions for archaeologists. One such puzzle revolves around the discovery of ancient stone tools on Sulawesi, an island in Indonesia, and what that timing says about their ability to cross Earth’s oceans.

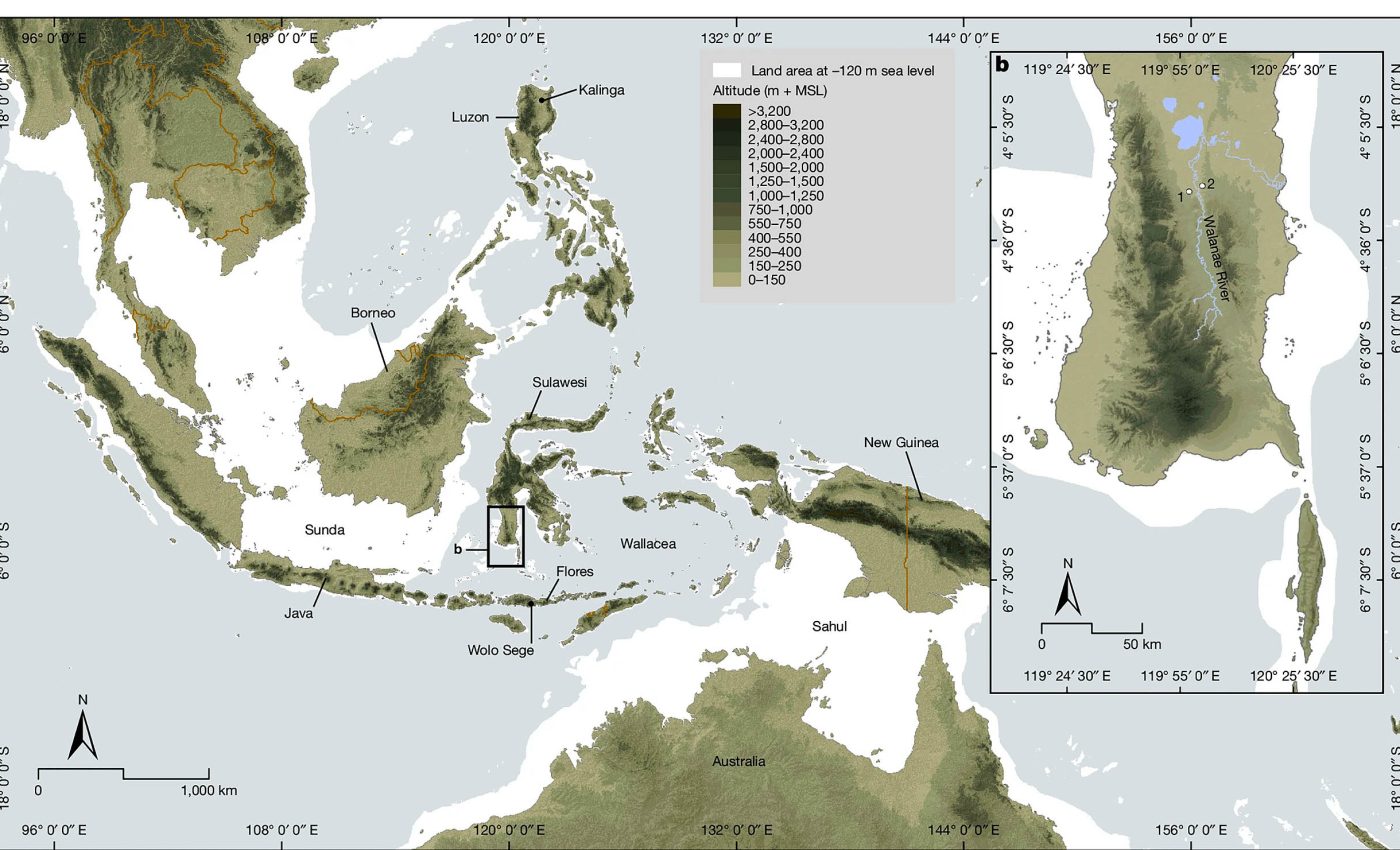

Sulawesi lies inside Wallacea, a string of islands between mainland Southeast Asia and Australia-New Guinea where deep water has always surrounded the land, even during ice ages when sea levels dropped and continents joined.

Any ancient hominin that reached Sulawesi or its neighbors had to cross open water, using rafts, natural debris, or simple watercraft.

Stone tools on Sulawesi

Researchers already knew that archaic hominins – earlier human species, not yet modern Homo sapiens – made sea crossings in a few places.

On Flores, stone tools show that hominins lived there more than a million years ago, and fossils of the small-bodied “hobbit,” Homo floresiensis, appear later.

On Luzon in the Philippines, stone tools and cut‑marked animal bones point to hominins roughly three‑quarters of a million years ago, followed by fossils of another small species, Homo luzonensis.

Sulawesi sat in the middle of this story as a puzzle. At Talepu, archaeologists found stone artefacts at least 194,000 years old, much older than the arrival of modern humans in the region around 70,000 years ago.

That still left a gap between Talepu and the much earlier records on Flores and Luzon, suggesting a missing chapter in Sulawesi’s early human history.

Chert flake and tools

The new work focuses on a site called Calio in the Walanae Depression of southwestern Sulawesi. This area preserves ancient river and floodplain deposits known as the Walanae Formation.

Calio first drew attention when a researcher spotted a flake of chert, a hard fine‑grained rock that often makes good stone tools, sticking out of a cemented gravel layer in a farm field.

The piece looked deliberately shaped rather than broken by chance. Archaeologists excavated in 2019 and expanded the work in 2021 and 2022.

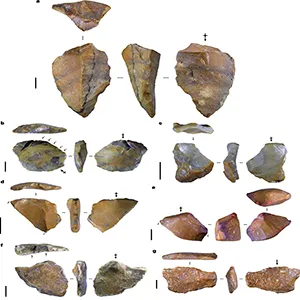

As the team dug through compacted river sands and gravels, they uncovered seven stone artefacts sealed within the deposits.

These were not loose surface finds that water might have moved; the tools sat locked inside the ancient river sediments.

The same layers held fossils of extinct animals: a large pig from the genus Celebochoerus, a young proboscidean (an elephant relative), a crocodile tooth, and some shark teeth.

Proving Sulawesi stones were tools

To show that these pieces were artefacts rather than random chert fragments, the researchers took a two‑step approach.

First, they compared sizes and found that the artefacts were, on average, noticeably larger than natural chert pebbles from the same sediments and formed a separate size group, rather than just being the biggest ordinary pebbles.

Next, they examined shape and fracture details. The artefacts show classic signs of intentional flaking: flat striking platforms, bulbs of percussion – the bulge where a hammerstone struck – and clear patterns of rippling flake scars.

Someone used hard‑hammer freehand percussion, with one stone held in the hand to strike another, to knock off controlled flakes.

In one case, a toolmaker struck a large flake into smaller flakes and retouched one edge to sharpen it, showing planning and skill. A river is very unlikely to break stones in exactly this way over and over again in the same spot.

Dating soil layers

The team then asked how old the tools were and combined two independent dating methods. The first, palaeomagnetism, relies on the fact that Earth’s magnetic field has flipped direction many times.

When sediments settle, tiny iron‑rich minerals align with the current magnetic field and lock in place as the layers harden.

Rock samples from the same layers as the artefacts show a reversed magnetic polarity, meaning they formed when the field pointed opposite to today.

The most recent major switch from reversed to normal, called the Brunhes–Matuyama boundary, happened about 773,000 years ago, so the Calio artefact layers must be older than that.

Dating extinct pig teeth

The second method focused on the Celebochoerus pig teeth from near the tools and used combined uranium‑series and electron spin resonance dating, or US-ESR.

After burial, natural radioactivity from the surrounding sediments and from elements inside the tooth gradually damages the enamel.

ESR measures how much damage has built up, and uranium‑series measurements model how uranium entered the tooth over time.

Together, these methods reveal how long the tooth has been buried. For these pig teeth, the US–ESR age came out to about 1.26 million years, with an uncertainty of ±0.22 million years, putting the likely age between 1.04 and 1.48 million years ago.

Because the pig jaw sits slightly above the deepest artefact‑bearing level, that age is a minimum, so the stone artefacts must be at least about a million years old and probably older.

Taken together, the magnetic signal and the US–ESR ages place the Calio tools in the Early Pleistocene and push the earliest known occupation of Sulawesi back by more than 800,000 years compared with Talepu.

That result puts Sulawesi in the same time frame as early hominin evidence from Flores and likely earlier than Luzon.

Lessons from the Sulawesi tools?

Even with this view of age and setting, the toolmakers themselves remain unknown. No hominin bones have turned up at Calio, only artefacts and animal fossils, and the flake‑based technology could fit several archaic species, including Homo erectus or a yet‑unknown island population.

Homo erectus had already spread from Africa into parts of Asia by this time, so it is one possible candidate for the people who shaped the Calio stones.

Researchers also cannot yet tell whether hominins stayed on Sulawesi continuously after their first arrival or whether separate waves of colonization and extinction came and went.

At Calio, one message stands out: long before modern humans evolved, hominins were not just walking over land bridges; they were repeatedly reaching deep‑water islands in Wallacea and crossing significant sea gaps.

These travelers, in some manner as yet unknown to science, reached the islands much sooner than earlier studies suggested.

The full study was published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–