Humans and all life on Earth trace their roots to a common ancestor called 'Asgardians'

Every human body is built from eukaryotic cells, which have a nucleus, DNA packaged into chromosomes, and internal compartments. In contrast, bacteria and archaea have simpler cells.

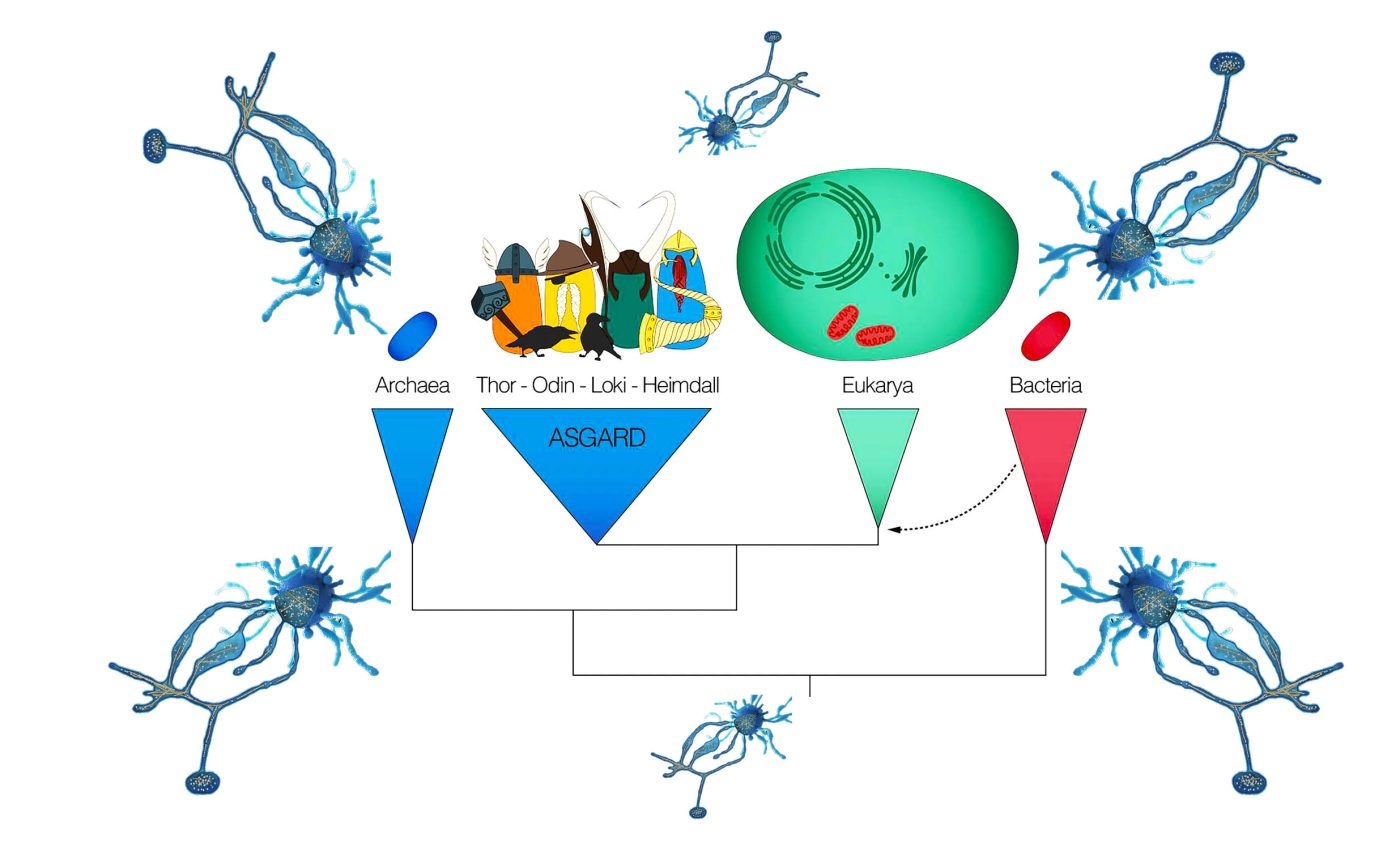

For many years, textbooks taught a “three-domain” tree of life with bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes on three branches.

New DNA evidence has pushed researchers toward a “two-domain” tree where archaea and eukaryotes sit much closer together.

Asgard archaea: Our microbial roots

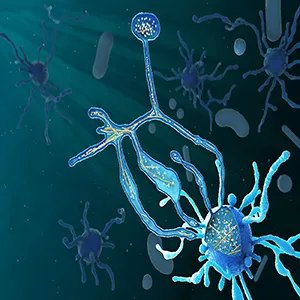

Within archaea, one cluster, the Asgard archaea, stands out because it includes some of the strangest archaeal genomes known.

Earlier work hinted that this group might sit near the line of eukaryotes that eventually produced complex cells like ours.

Eukaryotes are complex organisms whose cells contain a nucleus – a group that includes all plants, animals, insects, and fungi.

That hint set up a puzzle about ancestry: the team wanted to know which Asgard lineage gave rise to our cells, how its genome changed, and what kind of lifestyle that ancestor had.

“So, what events led microbes to evolve into eukaryotes?” said Brett Baker, University of Texas Austin (UT Austin) associate professor of integrative biology and marine science. “That’s a big question. Having this common ancestor is a big step in understanding that.”

Hunting Asgards archaea is hard

Asgard archaea rarely grow in laboratory dishes, so the team went looking for them in nature. They sampled hot springs, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, marine sediments, and other sediments at 11 sites.

The team scooped up mud and mineral deposits, extracted DNA, and used computers to rebuild that mixed DNA into separate genomes known as metagenome-assembled genomes, or MAGs.

“Imagine a time machine, not to explore the realms of dinosaurs or ancient civilizations, but to journey deep into the potential metabolic reactions that could have sparked the dawn of complex life,” said Valerie De Anda, a researcher in Baker’s lab.

“Instead of fossils or ancient artifacts, we look at the genetic blueprints of modern microbes to reconstruct their past.”

The team recovered 63 new Asgard genomes from the samples, dramatically broadening the group’s known diversity.

Within the Heimdallarchaeia subgroup, they found genome sizes varied widely and identified a new order, Hodarchaeales, that includes some of the largest genomes.

Reading the genomes

To see how these Asgards relate to one another and to us, the researchers built evolutionary trees using sets of proteins shared across archaea and eukaryotes.

After analyzing the genomes of hundreds of archaea, which are microbes distinct from bacteria, researchers from UT Austin and other institutions found that eukaryotes likely evolved from a single common ancestor within the Asgard archaea.

After all the tests, the pattern that kept appearing showed eukaryotes sitting as a “well-nested clade” within Asgard archaea.

In these trees, eukaryotic cells form the closest sister group to Hodarchaeales inside Heimdallarchaeia, supporting the idea that complex cells arose from within the archaeal domain rather than from a separate branch.

Tracing ancient lifestyles

The team then compared gene families across many archaeal genomes and reconstructed what ancestral genomes likely contained at different points on that tree.

They found that ancestors of Asgard groups, especially Lokiarchaeia and Hodarchaeales, showed high rates of gene duplication, while their gene loss rates stayed similar to or lower than in other archaea.

As a result, ancestral Asgard genomes tended to be larger and encode more proteins than typical archaeal ancestors, with the ancestor of Hodarchaeales likely holding over 4,000 proteins compared with around 3,100 proteins predicted for the common ancestor of all Asgard archaea.

Using this reconstructed gene content, the scientists inferred how the ancestors lived. For the last common ancestor of Asgard archaea, they identified genes for the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway, which lets cells use inorganic carbon compounds to build organic molecules.

That pattern points to a chemolithotrophic lifestyle that draws energy from inorganic chemicals instead of organic food and to signs that this ancestor preferred very high temperatures, consistent with a hyperthermophilic origin in hot environments.

They treated that earliest ancestor as a “great-great-great…-grandmicrobe” and asked what temperature it liked and what it ate.

Ancestor closest to our cells

As evolution moved toward Heimdallarchaeia and then Hodarchaeales, the lineage leading to the common ancestor of Asgard archaea and eukaryotes lost the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway.

That lineage then shifted to heterotrophy, gaining energy from organic compounds, likely by fermentation.

The predicted central carbon metabolism at that stage included pathways very similar to those in modern eukaryotic cells, such as the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, a standard form of glycolysis, and a partial oxidative pentose phosphate pathway.

For the ancestor closest to us, the common ancestor of Hodarchaeales and eukaryotes, the analyses point to a mesophilic lifestyle with an optimal growth temperature between typical room and body temperatures rather than boiling heat.

That ancestor used a complete electron transport chain and performed anaerobic respiration using nitrate as the final electron acceptor.

So, our cellular “grandparent” may have lived in oxygen-poor but chemically-rich environments and made ATP using nitrate instead of oxygen.

“This is really exciting because we are looking for the first time at the molecular blueprints of the ancestor that gave rise to the first eukaryotic cells,” De Anda said.

The name Hodarchaeales comes from Hod in Norse mythology, a blind god who is tricked into killing his brother Baldr. “I keep joking in my talks that ‘We are all Asgardian’,” Baker said. “Now that’s probably going to be on my tombstone.”

Lessons from Asgard archaea

The teams findings suggest that the Asgard ancestor of eukaryotes already had a toolkit for bending membranes, shuttling proteins, and organizing the inside of the cell.

“We don’t know, in these Asgards specifically, what the gene duplications led to,” Baker said. “But we know in eukaryotes that gene duplications led to new functions and an increasing of cellular complexity. So, we think that that’s one of the ways that Asgards led to the innovations that define eukaryotes.”

Scientists studying archaea have found many proteins that were once thought to be exclusive to eukaryotes, and Baker said that raises the question: What functions are these eukaryotic proteins serving in the archaea?

“I think studying these simpler forms of life and their eukaryotic characteristics is going to tell us a lot about ourselves,” Baker concluded.

To sum it all up, studying Asgards helps explain how something as complex as a human cell could gradually evolve from something that still looked, on the surface, like a “simple” microbe.

But here’s the best part: In Norse mythology, being an “Asgardian” means Thor is a distant relative. And let’s be honest, who wouldn’t want Thor in their family tree?

The full study was published in the journal Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–