Humpbacks are the only whales capable of using the 'bubble-net feeding' strategy

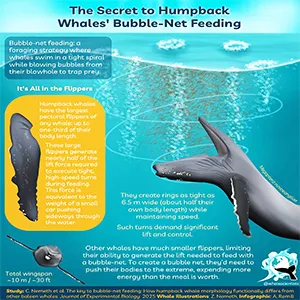

A new study reveals that among seven baleen whale species, only humpbacks can execute the high-performance turns essential for “bubble-net feeding.” This incredible feeding strategy involves whales releasing bubbles in a ring to corral prey.

The research, led by University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa graduate Cameron Nemeth, highlights the special role of humpback pectoral flippers in achieving this maneuver.

The findings shed light on the biomechanics behind one of the ocean’s most iconic hunting strategies.

Nemeth conducted the study as part of a larger project at the Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology’s Marine Mammal Research Program (MMRP).

Using drones and noninvasive suction-cup tags, his team quantified the turning performance required for solitary bubble-net feeding.

Whales and bubble-net feeding

“The fact that humpback whales’ pectoral flippers enhance their maneuverability wasn’t the most surprising part of our study, as there have been previous studies on the morphology of these flippers,” said Nemeth.

“However, it was shocking to discover that among thousands of turns from a variety of behavioral states, no other species of whale examined were achieving the turning performance required to create a bubble-net.”

This discovery shows how unique humpbacks truly are compared to other baleen whales. Even though other species may seem capable of turning sharply, their physical structure makes bubble-net feeding highly inefficient.

In contrast, humpbacks have adapted perfectly to this demanding strategy, giving them an advantage when hunting smaller or scattered prey.

Understanding baleen whales’ diet

Baleen whales eat some of the tiniest creatures in the ocean, even though they’re among the largest animals on Earth.

Instead of teeth, they have long plates of baleen – think of them like giant combs made of keratin, the same stuff as your fingernails.

When a whale takes in a huge mouthful of water, it pushes the water back out through the baleen, trapping food inside.

Their menu usually includes krill, plankton, and small schooling fish like anchovies or herring, depending on the species and where they live.

What’s amazing is the sheer volume they eat. A blue whale, for example, can gulp down several tons of krill in a single day during feeding season.

These whales don’t nibble all year round; they often migrate thousands of miles between feeding grounds in cold, nutrient-rich waters and breeding grounds in warmer seas where food is scarce.

Flippers help with bubble-nets

The research highlights that humpbacks’ large flippers can produce nearly half of the force required for turning.

This efficiency means humpback whales use less energy while executing bubble-net feeding compared to other whale species.

For others, even attempting such maneuvers would demand far greater energy expenditure, making it impractical.

“This is a great example of a collaborative research project that took advantage of datasets from 28 different research organizations across six countries,” said Lars Bejder, research professor at HIMB, principal investigator of MMRP, and co-author of the study.

“These sorts of initiatives are able to address questions that otherwise would be very difficult to answer.”

This collaboration allowed researchers to build a comprehensive dataset, strengthening the evidence for humpbacks’ unique hunting edge.

Energy reserves for survival

The findings are especially important for Hawaiʻi. Humpback whales travel there in the winter, and while in the islands, they do not eat.

Instead, they survive solely on the fat and energy stored from feeding in Alaska. Knowing how well they hunt helps scientists assess their health, strength, and energy levels.

This knowledge also reveals how changes in the environment – such as shifts in prey or warming oceans – might affect their survival during long migrations and fasting. For Hawaiʻi and its people, protecting humpback whales depends on such careful research.

Studies like this also guide conservation by highlighting the real challenges whales face as they manage their limited energy reserves and prepare for future journeys.

Research, culture, and continuity

Nemeth led this large-scale project during his final undergraduate semester and will continue with the MMRP as he transitions into a Ph.D. program in 2026.

He will oversee the lab’s ongoing humpback whale project in Maui, ensuring long-term continuity of this important research.

In an additional milestone, Nemeth translated the study’s abstract into Hawaiian, collaborating with a Hawaiian language professor to refine the text.

This marks one of the first times a scientific paper in this field has included a Hawaiian-language abstract, setting a precedent for future publications.

By merging cutting-edge science with cultural respect, this step opens the door for broader community engagement with marine biology research.

It shows how scientific work can honor local traditions while still advancing global knowledge and understanding.

The study is published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–