Jaw fossil reveals fruit-eating mammal from the dinosaur age

Mongolia’s Gobi Desert has long been a treasure trove for dinosaur fossil hunters. But every so often, it reveals a smaller, subtler wonder that shifts how we understand ancient life.

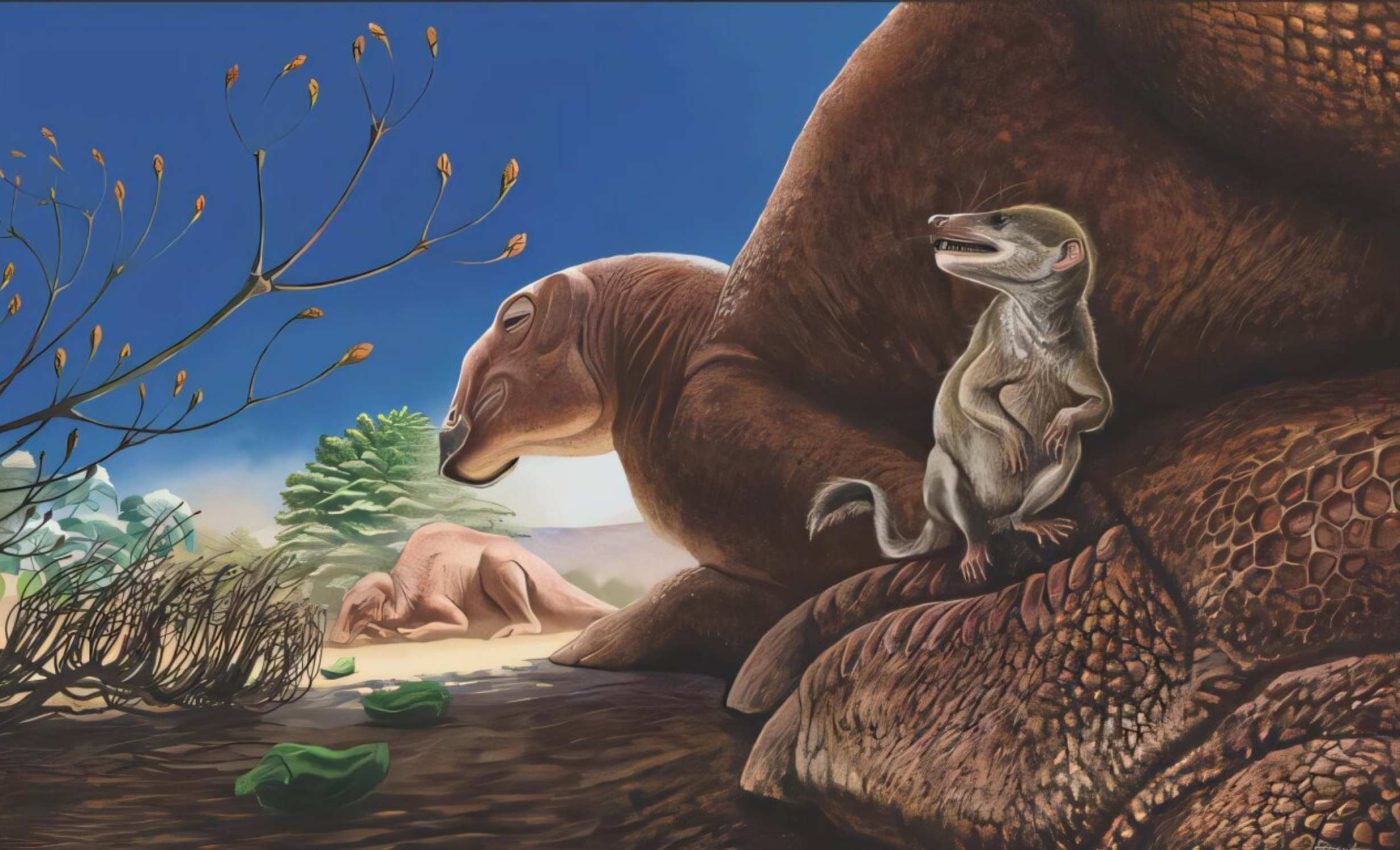

A recent study has revealed Ravjaa ishiii, a new mammal species from the Late Cretaceous. Unearthed in the Bayanshiree Formation of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, this discovery expands our view of early mammalian life inland from ancient coastlines.

Named in honor of Dulduityn Danzanravjaa, a revered 19th-century Buddhist monk, and Kenichi Ishii, the former director of the Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences, this mouse-sized mammal belongs to the extinct family Zhelestidae.

The study, which is published in Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, was a collaboration between researchers from Japanese and Mongolian institutions.

Fossil is from a new genus

During a 2019 expedition, researchers uncovered a one-centimeter partial jaw in a fluvial sandstone layer.

This zone, which is rich in small vertebrate remains, had previously yielded only two fragmentary mammal specimens. The jaw – catalogued as MPC-M 100s/001 – showed signs of zhelestid traits, but with unique twists.

The molars were unusually tall, and the mandible had structural features that are not seen in other zhelestids. These differences warranted the naming of a new genus and species.

Its presence in inland Mongolia marks a significant shift in our understanding of zhelestid distribution.

Tooth structure hints at fruit-based diet

The mammal jaw’s dental features suggest that Ravjaa ishiii had a robust molar structure fit for grinding seeds and fruit.

The new specimen’s molar morphology, in particular, would support a frugivorous or omnivorous diet. Compared to other therian mammals of the period – that are mostly insectivores – Ravjaa ishiii shows a more herbivorous tendency.

This aligns with the timing of the angiosperm expansion during the Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution (KTR). These flowering plants dramatically reshaped ecosystems because they provided new food sources that animals could exploit.

Fossil features show it’s a distant cousin

A detailed phylogenetic analysis placed Ravjaa ishiii as the sister taxon to the Zhelestinae, a subclade within Zhelestidae.

It stands apart because it lacks certain skeletal features, such as the labial mandibular foramen, and it exhibits uniquely large molars relative to its jaw height.

This makes Ravjaa ishiii not just the first zhelestid found in Mongolia, but one of the most anatomically distinct. Its molar-to-jaw size ratio is the highest known in the group.

First mammal jaw of its kind

Mongolia’s Upper Cretaceous formations, especially Djadokhta and Baruungoyot, have long been known for their rich deposits of mammal fossils.

However, these aeolian (wind-deposited) sites mostly lack zhelestids. Their dominance by multituberculates (another herbivorous group) suggested a different ecological makeup.

The Bayanshiree Formation, with its fluvial (river-deposited) nature, tells a different story. The increased water availability may have allowed zhelestids to thrive. Notably, no multituberculates have been found here, which hints at reduced competition.

Signs of plant-based diet

This find may support the idea that zhelestids preferred humid conditions and possibly competed with multituberculates. Their dental adaptations reflect a dietary overlap with multituberculates, which were also mostly herbivores.

Their absence from more arid formations and presence in river-influenced zones strengthens this environmental preference hypothesis.

Mammal jaw offers a glimpse into the past

“Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the publication process took longer than expected, but we were finally able to establish the scientific importance of this specimen,” said Tsukasa Okoshi, lead author from Okayama University of Science.

“We hope this research will serve as a starting point for further taxonomic studies of other small vertebrate fossils from the same site and era, and will ultimately help uncover the rich biodiversity – including dinosaurs – that once inhabited the Gobi Desert during the age of dinosaurs,” added Okoshi.

Mammal jaw changes dinosaur-era story

“Finding such a tiny fossil in the vast expanse of the Gobi Desert feels like a gift from the Gobi Desert. It’s nothing short of miraculous,” noted co-author of the study, Professor Mototaka Saneyoshi.

The discovery of Ravjaa ishiii does more than add a name to a list. It opens new directions in understanding mammalian life during a time of enormous change. The Gobi Desert, which was once a river-fed plain, is still revealing its ancient secrets – one tiny jaw at a time.

This find challenges long-held assumptions about mammalian habitats in the Late Cretaceous. It also highlights the importance of even the smallest fossils in piecing together Earth’s prehistoric ecosystems.

The study is published in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Image Credit: Kohei Futaka.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–