Archaeologists assemble King Richard III's microbiome using tooth plaque from 1485

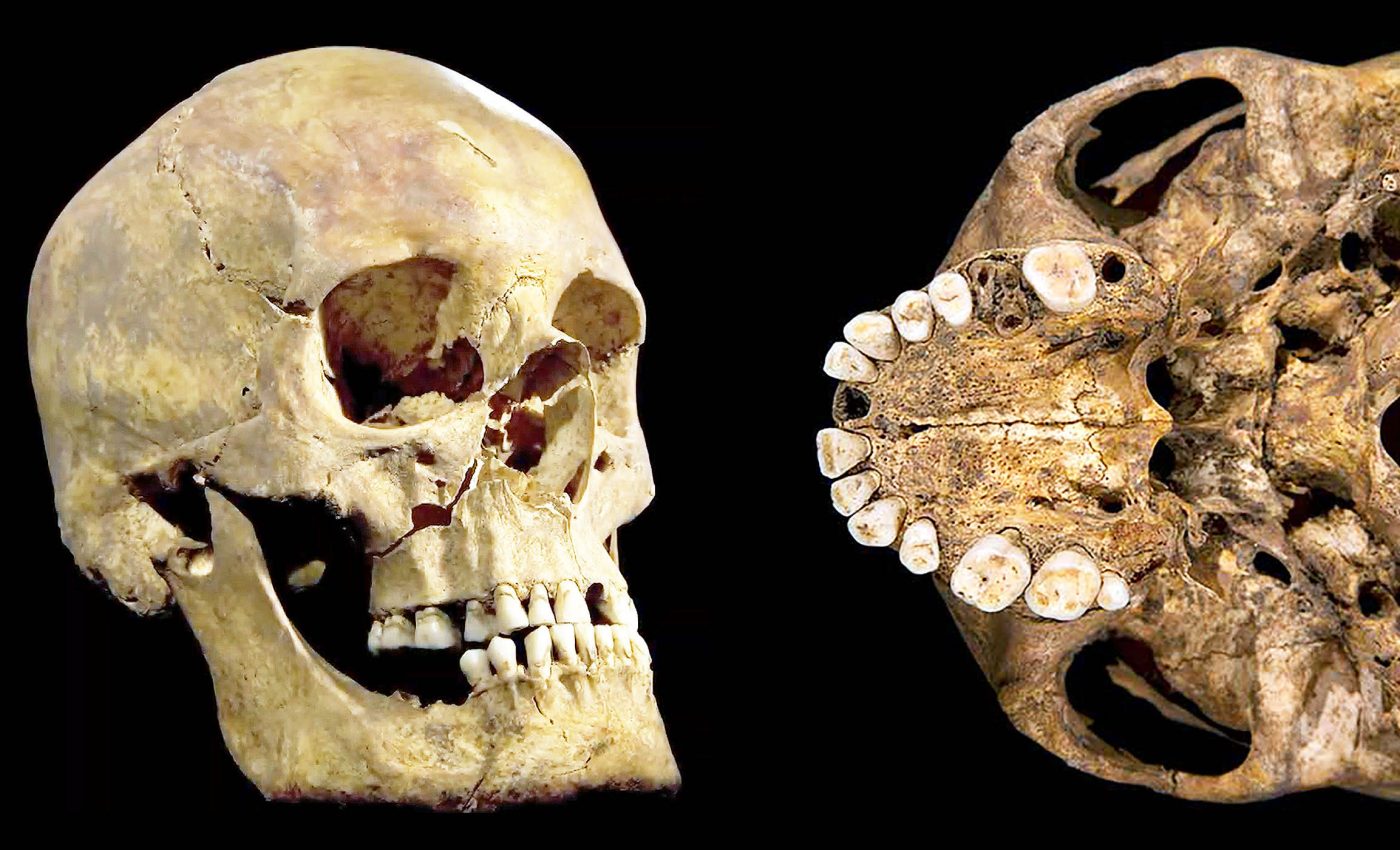

When archaeologists lifted a skeleton from beneath a parking lot in Leicester in 2012, they suspected they had found England’s most contentious king, Richard III. Blunt force trauma to the skull matched battlefield accounts, and a pronounced spinal curvature echoed descriptions of Richard III’s stance.

DNA testing later sealed the identification. Now, the same remains have delivered a fresh, intimate portrait: the first reconstruction of Richard III’s oral microbiome, assembled from calcified plaque on his teeth.

Studying King Richard III’s mouth

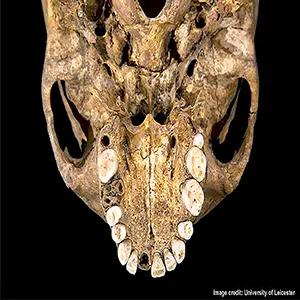

Led by geneticist Turi King at the University of Bath, researchers carefully scraped mineralized dental calculus from three well-preserved teeth.

Dental calculus – essentially fossilized plaque – is a molecular treasure chest. It traps and preserves fragments of ancient DNA from microbes, food, and the host, creating a durable record of life in the mouth.

In Richard’s case, the cache was extraordinary. The team reported recovering more than 400 million DNA sequences – an archaeological haul that startled even specialists.

King Richard’s mouth microbes

From the deluge of data, the scientists identified nearly 400 microbial species. Strikingly, the composition mirrors well-preserved calculus samples spanning 7,000 years from sites in England, Ireland, Germany, and the Netherlands.

In other words, despite royal status, frequent travel, and a wartime life, Richard’s microbial community looked broadly similar to those of ordinary people across centuries.

That continuity is a useful reminder: while diets and hygiene practices shift over time, the core cast of oral microbes has been remarkably stable.

The great reshaping of the human mouth – through sugar-rich diets and intensive dentistry – may be a more modern phenomenon.

King Richard III’s diet

While plaque in the mouth can sometimes preserve plant or animal DNA well enough to sketch a menu, Richard’s calculus was less forthcoming on that front. The team couldn’t recover enough dietary DNA to say much about what he ate.

Earlier isotope analysis of his bones had already painted a picture of elite consumption in the final years of his life.

He regularly drank nonlocal wines and ate game, fish, and birds – including swans, herons, and egrets. If those delicacies left a molecular breadcrumb trail in his mouth, it has long since faded beyond recovery.

Signs of a sore mouth

One microbe did stand out: Tannerella forsythia. It’s a well-known member of the “red complex” of bacteria associated with periodontal disease – a serious gum infection that destroys the bone supporting the teeth.

Its abundance in Richard’s plaque hints at a mouth under inflammatory stress. That’s no surprise in an era before toothbrushes, floss, or modern dentistry.

Records already note he had dental caries at death, aged 32. But a bacterial signature alone is not a diagnosis.

To establish whether Richard truly suffered from periodontal disease, researchers would need anatomical evidence of bone loss in the jaw. Such signs can sometimes be read from skulls with an intact maxilla and mandible.

What plaque can’t tell us

Even a study with hundreds of millions of reads has blind spots.

Oral microbiomes vary by geography within the mouth: the front versus the back, inner surfaces versus outer, gumline versus tongue. Sampling just three teeth offers only a partial map.

Weyrich noted that zooming in on a single tooth surface could offer finer detail.

Comparing it against precisely matched sites from other populations – such as the same molar surface from 15th-century Dutch burials – could sharpen what we can say about Richard’s unique oral ecology.

There’s also the unavoidable question of contamination and time. Seven centuries in the ground can change what survives – and how it adheres to the mineral matrix of calculus.

Richard’s plaque likely preserves a detailed snapshot of his living mouth through its diverse microbial sequences.

Lessons from King Richard III’s mouth

For a monarch immortalized as a villain by Shakespeare and haunted by the mystery of his missing nephews, the “Princes in the Tower,” this is a refreshingly human story.

The science doesn’t adjudicate court intrigues. Instead, it peers under the lip and into the daily wear of a medieval life – what it meant to eat, drink, endure pain, and smile in the late 1400s.

The methodological leap may prove the study’s most enduring legacy. Ancient dental calculus has already transformed our understanding of diet and disease in past populations.

This work shows just how far high-throughput sequencing can push that window open. Applying the same approach to other remains could illuminate how status, occupation, region, and hygiene shaped oral health across centuries.

Richard III’s remains have now yielded battlefield injuries, a genome, a scoliosis diagnosis, and – through his plaque – a living portrait of his mouth.

Scientists have reconstructed a king’s life from the bacteria on his teeth – an astonishing achievement that reminds us all share the same biology.

A preprint of the study can be found on bioRxiv.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–