Koalas have fingerprints nearly identical to humans, an evolutionary puzzle not yet solved

Nature loves to play quiet tricks on those who study it closely. Some of its greatest surprises aren’t buried deep in the ocean or hidden inside rare fossils – they sit right in front of us, unnoticed for decades. One such surprise came from an unlikely source: the soft, furry hands of a koala.

At first glance, nothing about a koala suggests human resemblance. They nap for hours, cling lazily to eucalyptus trees, and chew leaves with the patience of monks.

Yet when scientists looked closer, they found something uncanny – tiny ridges spiraling across their fingertips, just like human fingerprints.

The discovery baffled experts. How could an animal so different from us share such a detailed feature?

That small finding did more than raise eyebrows. It challenged long-held assumptions about evolution, grip, and touch.

The discovery hinted that nature sometimes arrives at the same brilliant solution twice, even in species separated by more than a hundred million years.

Understanding fingerprints – the basics

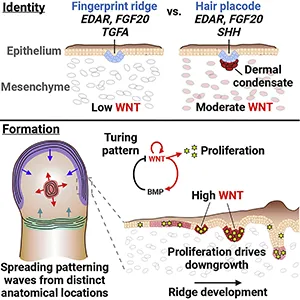

Fingerprints start forming before birth. Scientists recently found that these ridges grow from the outer skin layer (the epithelium) and begin a process that looks a lot like how hair follicles start to form.

Then that process abruptly stops. Because it stops, the skin doesn’t pull in the deeper “helper” cells it would need to make a full hair follicle, so instead you get a ridge.

The overall pattern – loops, whorls, or arches – comes from a chemical “conversation” in the skin that creates repeating patterns, similar to how a zebra gets stripes.

Complex signaling systems spread through the skin and interact in waves that start at specific spots on each finger.

As the waves move, meet, and merge – shaped by the finger’s local anatomy – they lay down bands of fast-growing cells.

That wave action sets the ridge directions and creates the familiar fingerprint types, along with endless small variations from person to person.

Humanlike fingerprints of koalas

In the mid-1990s, biological anthropologist Maciej Henneberg from the University of Adelaide made an unexpected finding while studying koalas in Australia. Their paws bore intricate loops and whorls just like human fingerprints.

“It appears that no one has bothered to study them in detail,” Henneberg told The Independent in 1996.

Even under a microscope, their prints mirrored ours so closely that investigators could, in theory, mistake one for the other.

“It is extremely unlikely that koala prints would be found at the scene of a crime,” Henneberg said.

His discovery did not solve mysteries in forensics, but it raised a more fascinating question – why do fingerprints exist at all?

Born with unique prints

Scientists have long understood how fingerprints form but not fully why they evolved. These unique ridges appear in three broad types – loops, whorls, and arches.

The general pattern comes from genetics, but tiny differences, called minutiae, form in the womb. Factors like amniotic fluid, fetal position, and touch shape every curve and ridge.

This is why no two humans share identical prints, not even identical twins. Each fingertip becomes a natural signature, recording both heredity and the environment before birth.

Grip, moisture, and control

For decades, scientists believed fingerprints improved grip. They seemed perfect for holding tools and climbing.

Yet in 2009, biologist Roland Ennos challenged this view. His research showed that the ridged structure actually reduced surface contact, which could lower friction instead of raising it.

Later studies added nuance, revealing a dual function involving moisture.

When fingers touch a hard surface, sweat seeps through pores and spreads along the ridges. This prevents both dryness and slippage by balancing moisture.

“This dual-mechanism for managing moisture has provided primates with an evolutionary advantage in dry and wet conditions – giving them manipulative and locomotive abilities not available to other animals,” researcher Mike Adams explained.

Fingerprints, it turned out, were not just about grip – they were about control for koalas.

Fingerprints enhance koala sensation

Fingerprints also heighten our sense of touch. Physicists at École Normale Supérieure in Paris discovered that the ridges amplify vibrations when fingers slide over rough textures.

These tiny waves travel to nerve endings, allowing humans to feel minute differences between surfaces. This understanding has inspired innovations in prosthetic design and touchscreen technology.

Engineers now aim to recreate the subtle communication between skin and surface – a bridge between biology and technology that began with a fingerprint.

Mirrored patterns in evolution

The connection between koalas and humans stretches beyond science fiction. Our last common ancestor lived over 100 million years ago.

Koalas shared fingerprints result from convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop similar traits under similar pressures.

Just as sharks and dolphins evolved sleek bodies for swimming, koalas and humans independently evolved ridged skin for gripping.

Nature often arrives at the same solution from different starting points, guided by survival’s demands.

Koalas use fingerprints wisely

Henneberg proposed that koala fingerprints evolved for delicate feeding and climbing. Koalas cling to narrow eucalyptus branches and pluck tender leaves with care.

Their cousins – wombats and kangaroos – lack such prints, suggesting this adaptation arose recently.

The friction and sensitivity provided by fingerprints help koalas balance while grasping specific leaves, a dance between strength and finesse. Nature shaped both humans and koalas to handle their worlds with precision.

Fingerprints remind us that evolution is both creative and consistent. Across millions of years and species, it rewrote the same pattern to meet similar needs.

What began as a quirk on a koala’s paw became a symbol of nature’s artistry – a sign that in the smallest patterns, great stories hide.

The study is published in naturalSCIENCE via Archive.org and ScienceDirect.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–