The most colorful lake in the world also has special healing powers

Lake Alakol has a way of catching you off guard. One moment the eastern Kazakh steppe looks endless and austere; the next, a glassy inland sea flashes jade and indigo against pale desert grass.

The water smells faintly briny, the wind pushes hard from the northwest, and swallows write quick loops over the breakers. Even without postcard fame, the lake feels unforgettable.

Locals have long trusted these salty swells to soothe eczema, achy knees, and winter-rough hands. Doctors in nearby Koktuma see a steady stream of visitors every June hoping the minerals can do what ointments never quite manage.

Science is still sorting out those claims, yet the setting alone – dry air, sun, and the hush of open land – works a kind of quiet magic.

Salt, silence, and healing water

Lake Alakol lies in a closed basin about 1,000 square miles wide, fed by the Urzhar and Emil rivers and cut off from every ocean. Whatever pours in stays until the sun lifts it back out; salt and other minerals remain behind.

Over centuries that constant loop raised salinity to roughly half that of the Atlantic, enough to keep freshwater fish away but gentle enough for bold swimmers.

The lake usually skins over for about two months at winter’s end, then cracks apart in early spring, leaving floating shards that sparkle like broken bottles.

Its surface size changes from year to year. A rainy spring can push the shoreline several hundred yards outward; three dry summers in a row pull it back.

Those swings tinker with salt levels and with the algae that tint the water turquoise or rust red. People used to call that chameleon quality “the water’s mood.”

Scientists at the European Space Agency, peering down with Sentinel-1 radar, now see the same shifts as color bands on monthly composites.

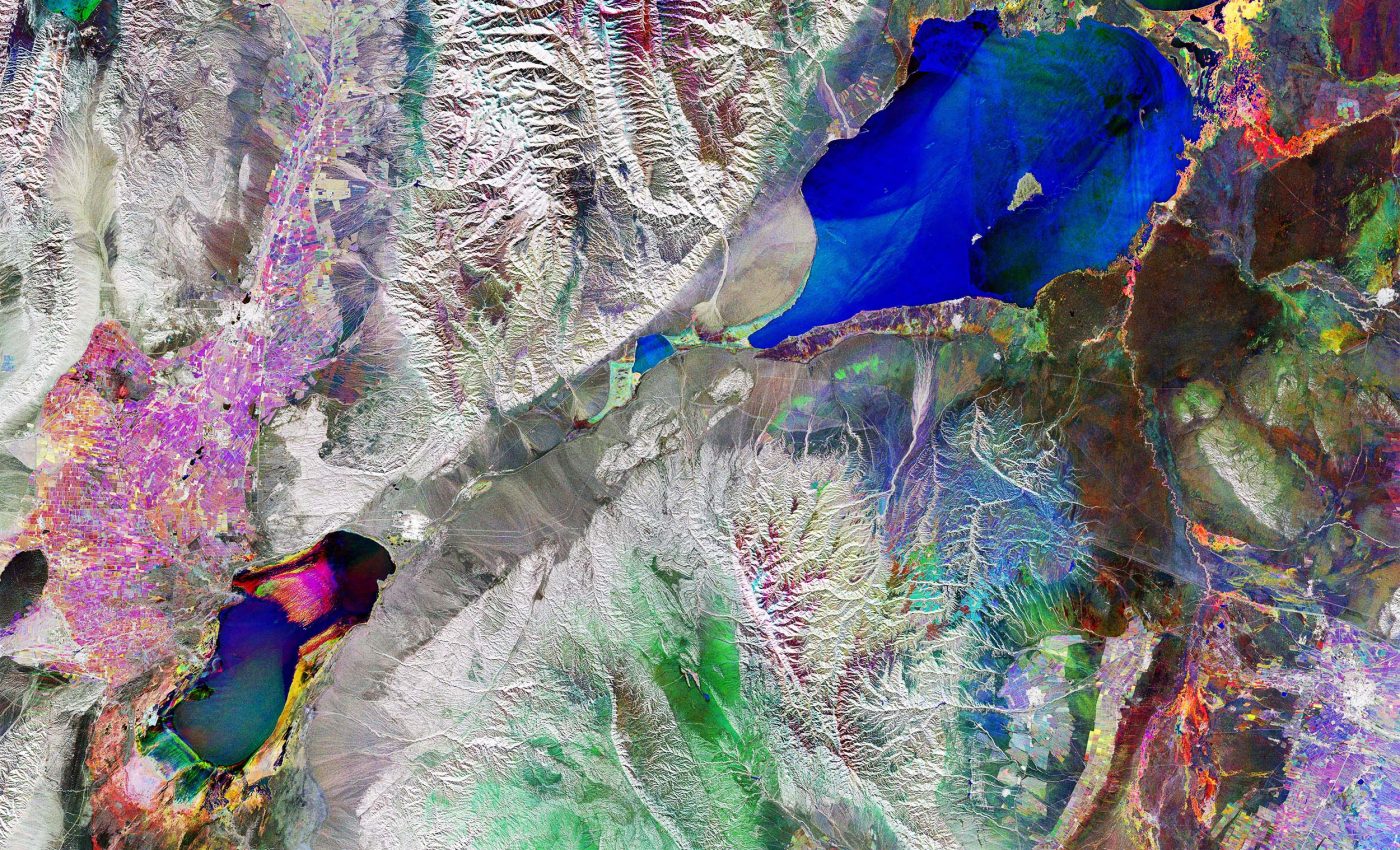

Lake Alakol captured by satellites

ESA analysts stacked three passes from March, April, and May 2025 and assigned them blue, green, and red.

Where the images overlap, the ground shows up charcoal or silver; where things change – ice breaking, soil drying, crops greening – new hues flare.

Alakol itself glowed mostly blue, proof that March ice still gripped much of the lake during the first scan. To the south, Aibi Lake in China’s Xinjiang region blushed pink where retreating water exposed salt flats in May.

The radar picture also picked out a fan-shaped burst of fields west of Alakol. Meltwater racing off the Dzungarian Alatau drops sand and silt as soon as it hits the plain, building fertile triangles perfect for wheat, onions, and apricots.

Farmers here work narrow plots, each stage of growth marking the fan with another shade. What looks abstract from orbit translates on the ground to young rows, shoulder-high stalks, and the buzz of irrigation pumps.

Birds also love Lake Alakol

Every spring, a sheet of feathers sweeps in from the south. Dalmatian pelicans cruise in first, their bills bright as fresh pumpkins. Greater flamingos follow, legs stilted, shoulders hunched like old men in pink coats.

For rare relict gulls – slate-gray wings, white eye crescents – Lake Alakol is one of the few safe nesting spots left on Earth. The birds crowd onto Ul’kun-Aral-Tyube Island, bickering over pebbly ground and guarding nests from sly foxes that swim across at night.

UNESCO folded the lake system into its Man and the Biosphere Programme back in 2013, noting its slot on the Central Asian Flyway.

Ramsar added a wetland designation as well, which nudged Kazakhstan to fence off breeding zones and limit boat traffic near the islands each breeding season.

Success shows up not in spreadsheets but in sound: a dull roar at dawn when thousands of wings clap the air at once.

People on the shore

Traders riding Silk Road spurs once skirted these banks, swapping Sogdian silver coins for Chinese silk bolts beneath flapping yurt doors.

Now tourists roll in on overnight trains from Almaty, step onto the platform at Koktuma, and blink at the sudden blue horizon. They rent bikes, buy salted perch for lunch, and post sunset shots that make the water look liquid copper.

Development remains modest – guesthouses, cedar-scented saunas, a scattering of cafés – but every new pier cuts habitat a little finer. Regional officials talk of zoning rules, stronger waste controls, perhaps a cap on shoreline construction.

Lake Alakol is at a crossroads

Hot summers already push evaporation higher, and climate forecasts warn that snowpack in the Dzungarian Alatau could shrink by mid-century.

If the inflow weakens, the lake’s salt will climb, and the delicate dance of microbes, brine shrimp, and birds could stumble.

Lake Alakol’s story reads like a lesson in balance. Mineral water glints under a hard sun, birds rest on speckled islets, farmers coax green rows from fan-shaped soils, and visitors float in water dense enough to lift them like corks.

None of those pieces can be pulled free without tugging the others loose. Stand on the shingle at dusk, feel a cool spray on your face, and the message is plain: salt and silence can endure only if we let them.

Zoom in and see more details of this magnificent lake by clicking here…

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–