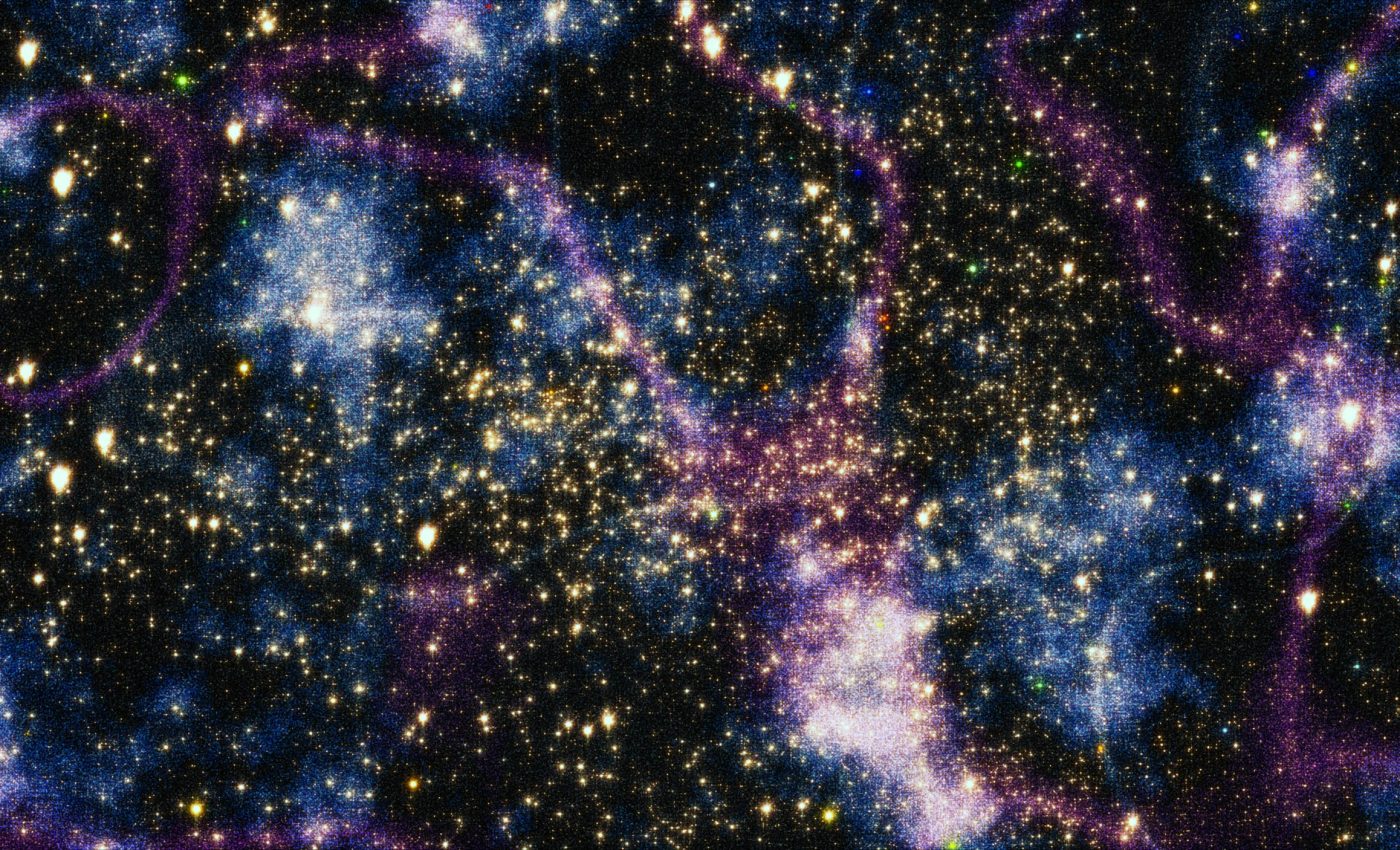

Largest spinning structure in the Universe resembles a 'teacups ride at a theme park'

Astronomers have spotted one of the largest rotating structures ever reported. It’s a knife-edge chain of hydrogen-rich galaxies, threaded inside a giant cosmic filament, about 140 million light-years away.

The structure stretches 5.5 million light-years yet spans only about 117,000 light-years across. It seems to move in two ways at once – each galaxy spins on its own axis, and the whole filament rotates together.

The discovery offers a rare laboratory for testing how the cosmic web funnels gas and angular momentum into galaxies. It also shows how those inputs shape galaxy growth from the early Universe to today.

How filaments shape galaxies

Cosmic filaments are the Universe’s grandest architecture: vast strands of dark matter and galaxies that channel material into clusters and groups. They do more than just connect the dots.

Filaments act as conduits for both mass and momentum, guiding gas inflow that feeds star formation and imprinting a preferred spin direction on the galaxies embedded within them.

Nearby filaments where many member galaxies share the same spin are ideal places to watch these processes in action. They also show signs that the entire structure may rotate as a whole.

In the new work, an international team led by the University of Oxford identified a remarkable system. Fourteen gas-rich galaxies sit in a stretched, “razor-thin” line inside a much larger filament that hosts more than 280 other galaxies and spans roughly 50 million light-years.

The alignment isn’t the only surprise. An unusually large share of these galaxies rotate in the filament’s direction, far more than random orientation would predict.

That coherence hints that large-scale structure may influence galaxy spins more strongly, or for longer durations, than many models assume.

A cosmic teacup ride

Velocity measurements show galaxies on opposite sides of the filament’s central spine moving in opposite directions, a telltale signature that the entire structure is turning.

Using dynamical models, the team inferred a rotation speed of about 110 kilometers per second. They also estimated the filament’s dense core radius at roughly 50 kiloparsecs (around 163,000 light-years).

“What makes this structure exceptional is not just its size, but the combination of spin alignment and rotational motion,” said co-lead author Lyla Jung.

“You can liken it to the teacups ride at a theme park. Each galaxy is like a spinning teacup, but the whole platform – the cosmic filament – is rotating too. This dual motion gives us rare insight into how galaxies gain their spin from the larger structures they live in.”

A spinning filament full of fuel

Clues suggest the filament is relatively pristine and still settling. The galaxies highlighted by the radio survey are rich in atomic hydrogen – the raw material for future stars – implying they are actively accreting or retaining gas.

Internal motions across the chain appear modest, a “dynamically cold” state consistent with an early evolutionary stage.

Hydrogen’s sensitivity to motion makes these galaxies excellent tracers of gas flow along the filament. They reveal how material is funneled toward galaxies and how angular momentum moves through the web to shape morphology, spin, and star-formation histories.

Hydrogen-rich populations are rare gifts for studying galaxy evolution because they record the balance between inflow, star formation, and feedback before the supply is exhausted.

When many galaxy spins converge and the backbone turns, astronomers can parse environmental contributions versus internally produced rotation.

A fossil record of cosmic flows

The team argues that this filament functions as a time capsule, preserving the imprint of large-scale flows and torques. “This filament is a fossil record of cosmic flows. It helps us piece together how galaxies acquire their spin and grow over time,” said co-lead author Dr. Madalina Tudorache from the University of Cambridge.

Because the cosmic web matures by developing filament rotations, systems like this one let astronomers test when that rotation begins and how long its influence lasts.

There are practical payoffs for precision cosmology, too. Coherent alignments of galaxy shapes and spins can contaminate weak-lensing results that average many orientations to map dark-matter structure.

Mapping real-world examples of spin-aligned, rotating filaments will help refine models that correct for these systematics in forthcoming surveys.

How astronomers found a spinning filament

The discovery leveraged South Africa’s MeerKAT radio array (64 linked dishes with exceptional sensitivity to faint hydrogen emission) via a deep survey known as MIGHTEE.

The radio view was matched with optical spectroscopy from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey to pin down distances, kinematics, and membership across the filament’s reach.

That multiwavelength approach revealed the filament’s “spine” of hydrogen-rich galaxies. It also exposed a larger environment filled with hundreds of neighbors woven into the same strand.

“This really demonstrates the power of combining data from different observatories to obtain greater insights into how large structures and galaxies form in the Universe,” said Matt Jarvis, a physicist at the University of Oxford.

Why this filament matters

Evidence shows that many galaxies along a single structure share a spin direction. The fact that the backbone itself is rotating also challenges the idea that spins “forget” their environment quickly.

Instead, it supports a picture where the cosmic web imprints a long-lived angular momentum blueprint, delivered by gas flows and tidal torques that operate over tens of millions of light-years.

Finding this behavior in a dynamically cold, gas-rich setting strengthens the link to formative epochs when filaments first funneled material into nascent galaxies.

As more sensitive radio surveys pair with massive spectroscopic campaigns, astronomers expect to discover additional examples. Those finds will help chart how common filament rotation is and how tightly galaxy spins track the large-scale flow.

The study is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–