Living baby colossal squid captured on video for the first time ever

When a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) named SuBastian dropped into the frigid waters near the South Sandwich Islands on March 9, the scientists watching the video feed expected fascinating footage of deep‑sea life. What they did not anticipate was history.

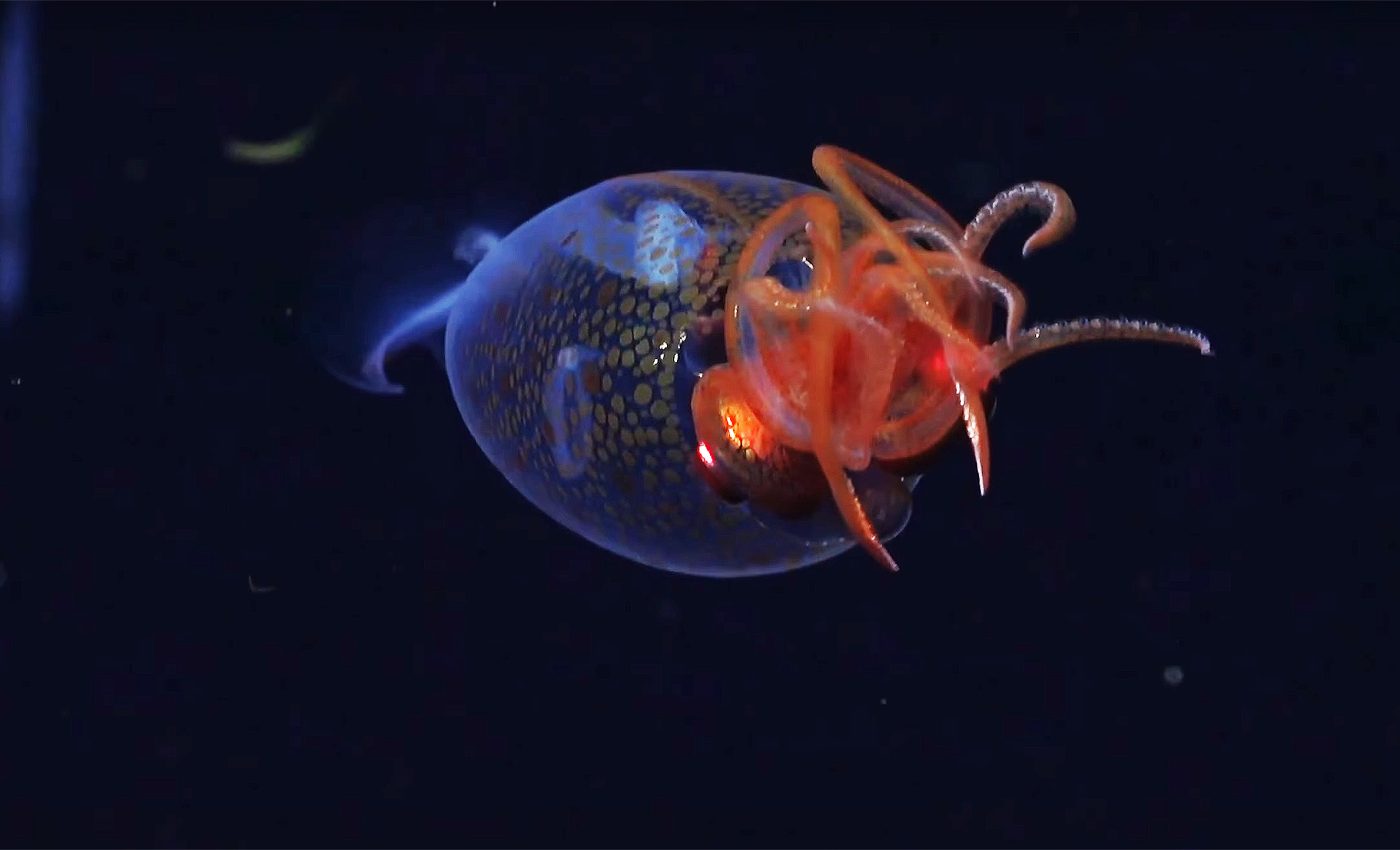

At roughly 600 meters (1,968 feet) below the surface, the ROV’s cameras recorded a transparent juvenile colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni). This is the first time this legendary species has ever been observed alive in its natural habitat.

A centennial surprise

The timing could not have been more fitting: 2024 marks one hundred years since zoologists first described and named the colossal squid, a member of the glass‑squid family Cranchiidae.

After a century of piecing together its existence from beaks found in sperm‑whale stomachs and the occasional adult cadaver tangled in fishing gear, researchers finally have moving images of a live individual.

“It’s exciting to see the first in situ footage of a juvenile colossal and humbling to think that they have no idea that humans exist,” said Kat Bolstad from Auckland University of Technology, one of the experts who verified the find.

“For 100 years, we have mainly encountered them as prey remains in whale and seabird stomachs and as predators of harvested toothfish.”

Colossal squid in every sense

Even as a youngster, the squid measured nearly 30 centimeters (one foot) long. As adults, these giants are thought to reach seven meters (23 feet) and tip the scales at up to 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds), making them the heaviest invertebrates on Earth.

Yet they remain among the least understood marine animals. Juveniles like the one filmed are nearly transparent; with maturity they darken and lose that ghostly clarity.

Adult colossal squids – possibly exhausted or dying – have occasionally surfaced on fishing lines, but until now none had been witnessed alive in the abyss where they thrive.

*Click image to launch the video.*

Dr. Aaron Evans, an independent authority on glass squids, helped confirm the juvenile’s identity. One key clue was a set of hooks located midway along each arm – distinctive hardware that differentiates M. hamiltoni from similar glass‑squid species.

Apart from those arm hooks, juveniles of several glass‑squid lineages can look remarkably alike: clear bodies, large eyes, and a pair of long feeding tentacles sporting sharp terminal hooks.

One breakthrough leads to another

The March discovery was not the research vessel’s only brush with squid lore. On January 25, during an earlier expedition to the Bellingshausen Sea near Antarctica, Falkor (too) scientists had filmed Galiteuthis glacialis, known as the glacial glass squid, alive and undisturbed for the first time.

That sighting came as the team surveyed the seafloor where a Chicago‑sized iceberg had calved from the George VI Ice Shelf. At 687 meters (2,254 feet) down, the transparent squid floated with its arms loose above its head – the so‑called “cockatoo pose” typical of glass squids.

“The first sighting of two different squids on back-to-back expeditions is remarkable and shows how little we have seen of the magnificent inhabitants of the Southern Ocean,” noted Schmidt Ocean Institute’s executive director Jyotika Virmani.

“Fortunately, we caught enough high‑resolution imagery of these creatures to allow the global experts, who were not on the vessel, to identify both species.”

A collaborative voyage of discovery

Both encounters occurred aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor (too), equipped with the ROV SuBastian and supported via satellite telepresence by taxonomists around the world.

The 35‑day cruise that netted the colossal‑squid footage served as the flagship expedition of Ocean Census, the largest global mission to discover marine life.

“It’s incredible that we can leverage the power of the taxonomic community through R/V Falkor (too) telepresence while we are out at sea,” said expedition chief scientist Michelle Taylor from the University of Essex.

“The Ocean Census international science network is proud to work together with the Schmidt Ocean Institute to accelerate species discovery and expand our knowledge of ocean life, live online with the world’s science community.”

A growing catalog of firsts

SuBastian has rapidly become one of the world’s premier vehicles for squid discovery. In 2020, it filmed the enigmatic Ram’s Horn Squid (Spirula spirula) alive for the first time.

In 2024, before the colossal‑squid milestone, it captured another first‑ever video of a deep‑sea squid in the genus Promachoteuthis. A fifth suspected first is currently under expert review.

“These unforgettable moments continue to remind us that the Ocean is brimming with mysteries yet to be solved,” Virmani said.

Significance of the colossal squid sightings

Beyond the thrill of seeing elusive creatures, such footage provides valuable clues about life histories, behaviors, and ecosystems that were once purely speculative.

Observing a juvenile colossal squid confirms its depth range and offers hints about its developmental stages.

Similarly, viewing G. glacialis in the wild helps scientists understand how glass squids position themselves in the water column, interact with predators, and potentially respond to changing ocean conditions.

These findings come at a time when the Southern Ocean is undergoing rapid environmental change. Ice‑shelf calving, warming waters, and shifting currents could reshape food webs. Documenting present‑day biodiversity is crucial for detecting future alterations.

Upcoming images of deep-sea life

The researchers now plan to analyze the new video frames for details such as muscle movements, fin strokes, and eye orientation – data points that, when compared with dead specimens, can illuminate how these squids hunt and evade predators.

The experts also hope to revisit the South Sandwich trench system to deploy environmental DNA (eDNA) samplers that might capture genetic traces from larger, unseen individuals.

For the public, these deep‑sea cameos kindle imagination. Once the stuff of sailor legend, colossal squids are no longer merely mythic giants – they are living animals caught on camera, navigating a twilight realm six football fields beneath the waves.

As technology pushes boundaries, the ocean continues to reveal that its most dramatic stories have yet to be told.

The Ocean Census is a partnership between the Schmidt Ocean Institute, the Nippon Foundation‑Nekton Ocean Census, and GoSouth (a consortium led by the University of Plymouth, GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research, and the British Antarctic Survey).

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–