Mammals have evolved to eat ants and termites 12 different times since the dinosaurs

Evolution often follows curious paths, especially when it comes to food. Over the past 100 million years, mammals have explored an incredible range of diets.

Some mammals graze on grass, others hunt prey, and a few even sip tree sap or dive for krill. But one of the strangest dietary turns comes from species that eat and depend deeply on ants and termites.

This peculiar choice may seem limiting, even risky. Yet, it has driven major transformations in anatomy, behavior and even survival strategies.

Dietary changes for mammals

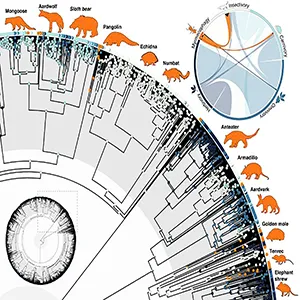

According to new research, mammals evolved ant and termite-only diets at least 12 separate times over 66 million years.

This shift, called myrmecophagy, followed the dinosaur extinction. It allowed ants and termites to thrive and opened a new food niche for mammals.

“There’s not been an investigation into how this dramatic diet evolved across all known mammal species until now,” said Phillip Barden of the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT).

“This work gives us the first real roadmap, and what really stands out is just how powerful a selective force ants and termites have been over the last 50 million years – shaping environments and literally changing the face of entire species.”

How mammals adapted to eat ants

Over 200 mammal species consume ants or termites occasionally. But just 20, like pangolins and anteaters, rely on them completely.

These true myrmecophages evolved long, sticky tongues and powerful claws. Many even lost their teeth.

To track this trend, the researchers collected diet records from 4,099 species. These came from nearly 100 years of scientific papers, field notes and conservation reports.

“Compiling dietary data for nearly every living mammal was daunting, but it really illuminates the sheer diversity of diets and ecologies in the mammalian world,” said Thomas Vida from the University of Bonn.

Small ant-eaters need to eat huge numbers to survive. Numbats eat around 20,000 termites daily. Aardwolves can eat over 300,000 ants in one night.

Understanding anteaters – the basics

Anteaters belong to the suborder Vermilingua, which literally means “worm tongue” – an apt name, since their tongues can extend up to two feet and flick in and out of their mouths up to 160 times per minute.

Modern-day anteaters don’t have teeth, so they rely on their sticky tongues and powerful stomachs to digest the thousands of ants and termites they consume daily.

Their long, tubular snouts house an excellent sense of smell, which is key to locating insect nests in the wild.

Despite their name, anteaters don’t just eat ants. They also snack on termites, and they’re careful not to destroy an entire colony – they’ll feed for just a minute or two before moving on, ensuring the nest can recover for future visits.

Giant anteaters, like the one pictured in this article, can grow over 7 feet long from nose to tail. These solitary animals roam grasslands and rainforests across Central and South America.

With their shaggy coats and slow, deliberate movements, they might seem awkward – but they’re incredibly strong, especially in their forelimbs, which they use to rip open tough termite mounds or defend themselves from predators.

The rise of ants and termites

The team grouped species by diet. From ant-only eaters to generalists. Then they mapped these onto a mammal family tree and ran evolutionary models.

The experts found at least 12 independent shifts to strict myrmecophagy. These happened in marsupials, monotremes and placental mammals. But not evenly. Some groups showed more change than others.

The researchers also looked back 145 million years to study the rise of ant and termite colonies. During the Cretaceous, ants and termites were rare. By the Miocene, 23 million years ago, they made up over a third of insect populations.

“It’s not clear exactly why ants and termites both took off around the same time. Some work has implicated the rise of flowering plants, along with some of the planet’s warmest temperatures during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum about 55 million years ago,” said Barden.

“What is clear is that their sheer biomass set off a cascade of evolutionary responses across plants and animals.”

Ant-eating mammals rarely change diets

Myrmecophagy arose more often from insect-eating ancestors than from carnivores. But surprisingly, carnivores like dogs and bears made the switch several times too.

“That was a surprise,” Barden said. “Making the leap from eating other vertebrates to consuming thousands of tiny insects daily is a major shift.”

Once a mammal becomes a myrmecophage, it rarely reverts. Only one genus, Macroscelides, the elephant shrews, ever switched back to a broader diet after specializing.

Eight of the twelve times mammals evolved to eat only ants or termites, just one species survived each time.

This limited survival suggests that highly specialized creatures, while successful in their niche, may face a greater risk of extinction due to changing environments, food scarcity, or habitat disruption over time.

Ant-eaters survive as insects spread

“In some ways, specializing on ants and termites paints a species into a corner,” Barden said. But for now, these specialists thrive.

Ants and termites now outweigh all wild mammals combined. Climate change favors species with massive colonies.

This shift may help ant- and termite-eating mammals, known as myrmecophages, survive and thrive. Their specialized diet could become a surprising advantage in a world increasingly ruled by social insects.

“If you can’t beat them, eat them,” Barden said. That idea, repeated across millions of years, has changed the face of mammals again and again.

The study is published in the journal Evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–