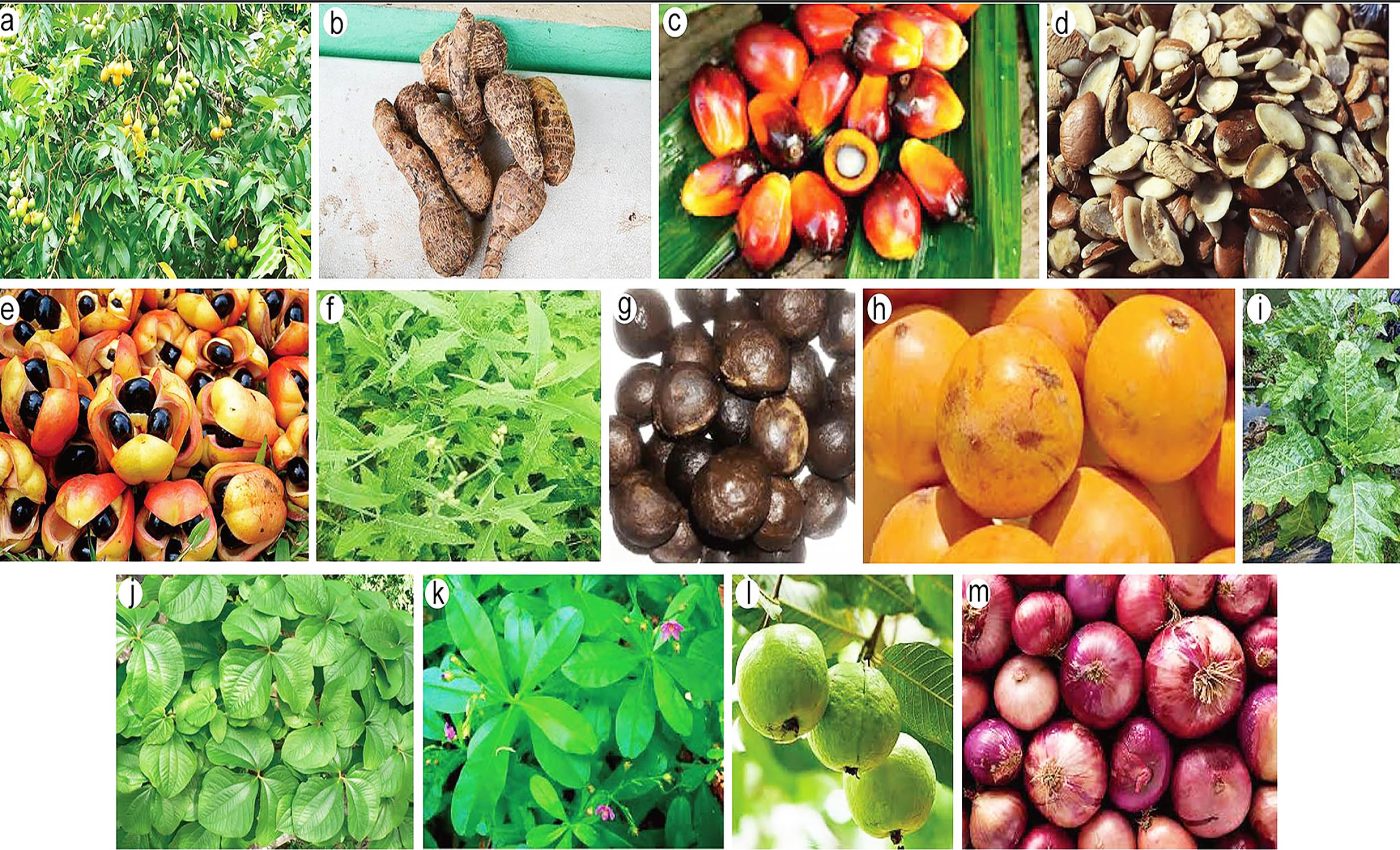

These food plants demonstrated natural anti-cancer properties in a recent study

Cancer remains a leading cause of mortality across the globe and Nigeria is no exception: Breast, cervical, prostate, and liver malignancies are climbing steadily despite wider access to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted drugs.

For many patients, however, modern treatment is difficult to afford. This has sparked renewed interest in a largely untapped yet promising resource: Nigeria’s indigenous food plants.

These plants – including their leaves, seeds, tubers, and fruits – are loaded with bioactive compounds. Laboratory studies show that many of these natural substances have the potential to slow or even halt tumor growth.

A growing body of evidence suggests that these plants, long consumed as part of the traditional diet, could be developed as low-cost, complementary tools in the nation’s fight against cancer.

Plants that prevent or halt cancer

Researchers have catalogued dozens of edible Nigerian species with measurable anti-cancer activity, but nine stand out for the breadth of experimental data already available.

Spondias mombin (hog plum) contains the flavonoid quercetin along with carotenoids that trigger apoptosis – the “self-destruct” program in malignant cells – while simultaneously tamping down inflammation.

Xanthosoma sagittifolium, a cocoyam cultivated widely in the humid south, produces tannins and other phenolics that cause leukemia cells to stall in the cell-cycle, blocking proliferation and reducing the formation of new blood vessels that tumors need in order to expand.

Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) is often maligned for ecological reasons, yet its vitamin-E–rich tocotrienols are potent antioxidants; in breast cancer models they lower cell viability and force cells into arrest, nudging them toward death.

Irvingia gabonensis, the African bush mango, supplies gallotannins that regulate metabolic pathways linked to tumorigenesis and stimulate immune surveillance.

Powerful cancer-fighting plant compounds

Allium cepa, the humble onion, is packed with organosulphur compounds as well as flavonoids that up-regulate detoxification enzymes, mop up DNA-damaging free radicals and may even help reverse multidrug resistance.

Blighia sapida (ackee) fruit, famous for its culinary role in Caribbean cuisine, also grows in Nigeria; laboratory work shows its flavonoids can hamper the ERK5 pathway, a key driver of aggressive breast cancer.

Dioscorea dumetorum, a wild yam, synthesizes diosgenin – long prized in the pharmaceutical industry as a raw material for steroid hormones – which shuts off the pro-survival NF-κB and MAPK cascades in cancer cells.

Psidium guajava (guava) leaves have been used for generations to treat diarrhea; now their tannins and phenolic acids are recognized for inducing apoptosis and shielding DNA from oxidative injury.

Finally, Talinum triangulare, the protein-rich “waterleaf,” contains quercetin and other antioxidants that bolster immune responses and hinder tumor growth in vitro.

Diverse plants with similar strategies

Despite their botanical diversity, these species rely on a handful of overlapping biochemical strategies.

First and foremost is apoptosis induction: they activate pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax while down-regulating anti-apoptotic factors like Bcl-2, tipping the balance toward cell death.

Many extracts also impose cell-cycle arrest at the G1/S or G2/M checkpoints by interfering with cyclin-dependent kinases; deprived of the green light to divide, cancer cells accumulate DNA damage and succumb. Angiogenesis – the sprouting of new blood vessels that feed a tumor – is another frequent target.

Compounds from cocoyam, yam and hog plum have been shown to lower levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and related signals, choking off the nutrient supply to nascent tumors.

Inflammatory enzymes (COX-2, iNOS) and reactive oxygen species are suppressed as well, reducing the chronic inflammation and oxidative stress that often initiate or accelerate malignancy.

Bridging tradition and modern oncology

While pre-clinical data are encouraging, several hurdles must be cleared before Nigerian food plants can take their place beside paclitaxel or cisplatin.

Bioactive composition varies by soil type, rainfall pattern and harvest time; rigorous agronomic studies are needed to standardize cultivation and extraction.

Dosage, toxicity and potential interactions with conventional drugs remain largely untested in humans. Well-designed clinical trials – randomized, placebo-controlled and sufficiently powered – are essential if these botanicals are to earn a formal role in oncology clinics.

Another challenge is the disconnect between traditional knowledge holders and laboratory scientists.

Ethnobotanical surveys can help bridge that gap, ensuring that leads chosen for development reflect community practices and dietary realities.

Public-health campaigns, meanwhile, could educate physicians, pharmacists, and patients about the evidence base for plant-derived adjuncts, avoiding unsubstantiated claims while highlighting genuine benefits such as reduced side-effects or improved quality of life.

Cost-effective, renewable treatments

If these hurdles are overcome, the payoff could be substantial. Many of the plants grow wild or are already farmed for food, implying a local, renewable supply chain.

Extracts could be formulated as teas, capsules or functional foods, lowering barriers to access in rural areas where oncology centers are scarce.

Combining plant-based agents with lower doses of chemotherapy or radiation might retain efficacy while mitigating nausea, hair loss, and myelosuppression – side-effects that often deter patients from completing treatment.

Fighting cancer with plants: Future research

Future research should prioritize mapping the full chemoprofile of each candidate plant. This should also include identifying synergistic combinations and unravelling pharmacokinetics in vivo.

Genomic and metabolomic tools can accelerate the discovery of lead molecules, while nanotechnology may enhance their bioavailability. Collaboration between Nigerian universities, pharmaceutical firms, and international cancer institutes will be vital to secure funding and regulatory approval.

Ultimately, Nigeria’s indigenous food plants harbor a rich arsenal of anticancer phytochemicals that attack tumours through multiple, complementary pathways.

Integrated with evidence-based medicine, these botanicals could broaden the therapeutic arsenal, reduce treatment costs and bring culturally familiar options to patients. Harnessing the plants may demand careful science, but the potential rewards will justify the effort.

The study is published in the journal Future Integrative Medicine.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–