Many women confuse the first symptoms of ovarian cancer with simple weight gain

Bloating is the symptom that most often alerts medical professionals to the presence of ovarian cancer. About 75 percent of diagnoses are stage 3 or 4, meaning the cancer has already spread beyond the ovaries to the abdomen, lymph nodes, or even distant organs by the time it is found.

The warning signs are vague and there is no proven screening test for people without symptoms. That gap keeps clinicians at major centers in Minnesota focused on what to notice and when to act.

Why bloating gets overlooked

Ovarian tumors can trigger ascites, the buildup of fluid inside the abdomen. The belly firms and swells, which can look like ordinary weight gain.

People often chalk it up to eating more or moving less. The confusion lingers because midlife weight shifts are common and gradual.

The research was led by Nagarajan Kannan, Ph.D., at Mayo Clinic. His work focuses on fallopian tube cell development and early ovarian carcinogenesis.

“We know that the most aggressive and common form of ovarian cancer often actually starts in the fallopian tube,” said Jamie Bakkum-Gamez, M.D., gynecologic oncologist at Mayo Clinic.

Those early changes can hide in plain sight. Feeling full after a few bites is another red flag. Clinicians call this early satiety, feeling full after a small meal.

What to watch for, and when to act

Common symptoms include bloating, pelvic pressure, abdominal or back pain, feeling full quickly, and bathroom habit changes. Urinary urgency or frequency can appear because a growing mass crowds the bladder.

Symptoms that are new, frequent, and persistent warrant a deeper evaluation. Patterns matter more than any single off day.

Track how often you feel a symptom and how long it lasts. If it continues for two weeks or more, bring that record to your visit. Talk with a gynecologic clinician if bleeding happens after menopause. That sign needs prompt attention.

Ovarian cancer screening falls short

For people without symptoms who are not at high genetic risk, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend routine screening for ovarian cancer. Tests like pelvic ultrasound and CA-125 have not lowered deaths when used for screening.

False positives can lead to invasive surgery in people who do not have cancer. That is why guidelines stress symptom awareness over blanket testing.

Levels of CA-125, a blood protein tracked in some cancers, can increase for many noncancer reasons. Infection, fibroids, and menstruation can all nudge it upward.

Imaging helps when symptoms are present, but very early tumors are often too small to see. That is another reason why careful tracking of symptoms matters.

What increases ovarian cancer risk

Inherited changes in the tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, raise lifetime risk substantially. For ovarian cancer, the National Cancer Institute estimates that 39 to 58 percent of women with harmful BRCA1 changes and 13 to 29 percent with harmful BRCA2 changes will develop the disease.

Family history can offer early clues. A pattern of breast, ovarian, or fallopian tube cancers should prompt a conversation about genetic counseling.

Some women reduce risk by removing the fallopian tubes during other pelvic surgery. That strategy is called opportunistic salpingectomy, and it may be carried out at the same time as a hysterectomy or tubal sterilization for people who are done with childbearing.

The goal is to lower the chance of future ovarian cancer that starts in a tube.

What the fallopian tube tells us

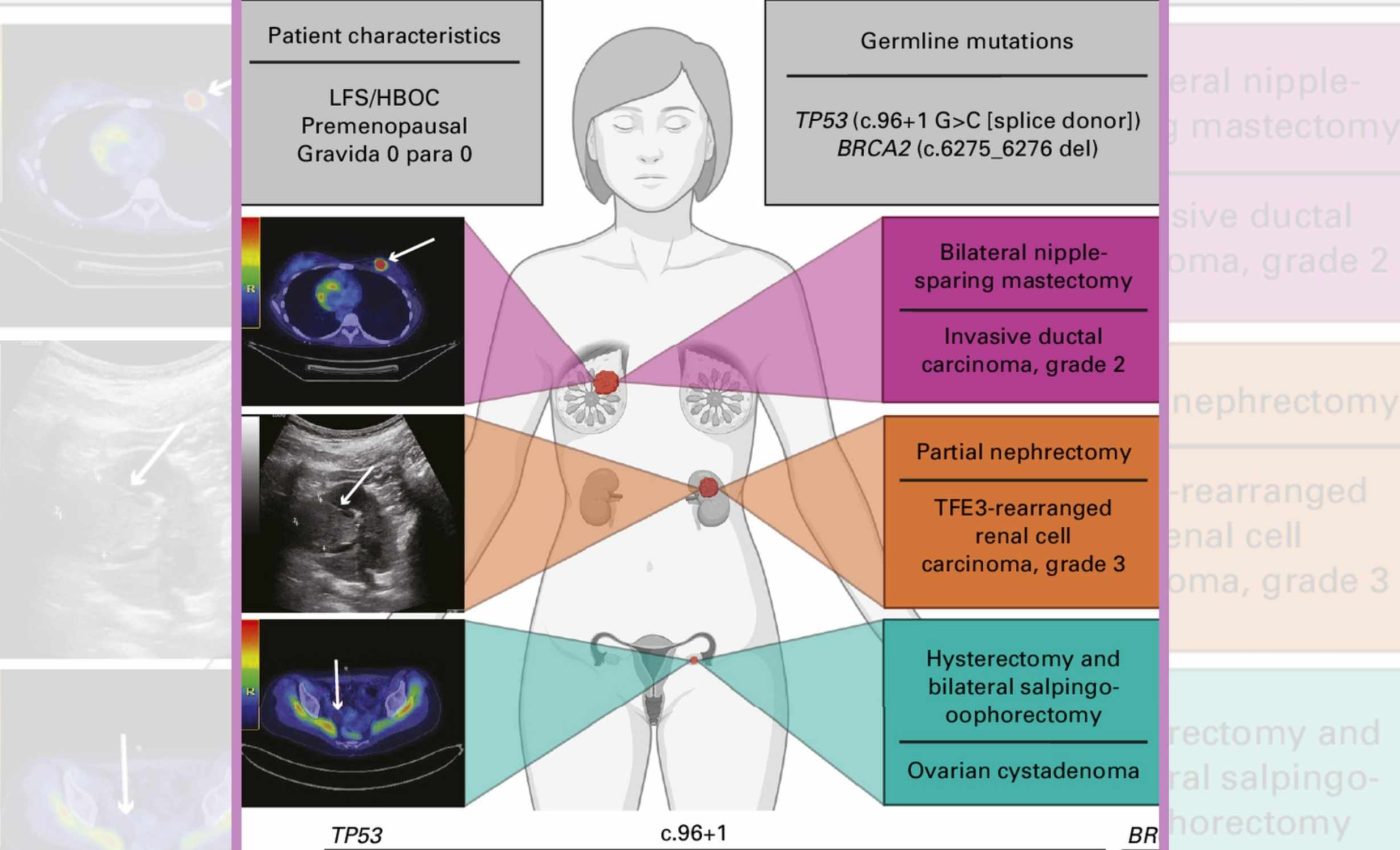

A recent study from Mayo Clinic profiled fallopian tube cells in a young patient with rare dual TP53 and BRCA2 mutations. The team saw fewer multiciliated cells and signals of chronic inflammation in the tube’s lining.

Those cellular shifts echo what pathologists see before invasive cancer. They suggest a long runway from earliest change to detectable disease.

“We know the fallopian tube may hold keys to prevention,” said Bakkum-Gamez. That is why researchers are mapping early cell behavior.

“These insights could pave the way for future strategies to detect the disease in its earliest, precancerous stages when prevention is still possible,” said Kannan. Work like this points to smarter surveillance for those with inherited risk.

Scientists also look for the p53 signature, the earliest fallopian tube precancerous change. It marks a small cluster of cells with telltale TP53 activity.

The fallopian tube idea also explains why removing tubes can help. If the origin sits in the tube, cutting the fuse may lower the subsequent risk.

A simple plan for paying attention

Know your baseline. If bloating, fullness, or urinary changes break that pattern and stick around, make an appointment. Share family history, including cancers on the father’s side. Genes come from both parents.

Ask if your symptoms warrant a pelvic exam or ultrasound. Testing should be targeted to a real change, not used as a general screen.

Discuss prevention steps during planned gynecologic surgery if you are done having children. Decisions should weigh age, fertility plans, and personal risk.

The study is published in JCO Precision Oncology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–