Mars had massive river systems across the planet that were 'potential cradles for life'

Billions of years ago, scientists believed Mars supported more than a few scattered gullies or lone streams. A new study reveals that the planet once supported a full hierarchy of large, interconnected river basins – organized drainage systems that rival Earth’s in structure, even if not in scale.

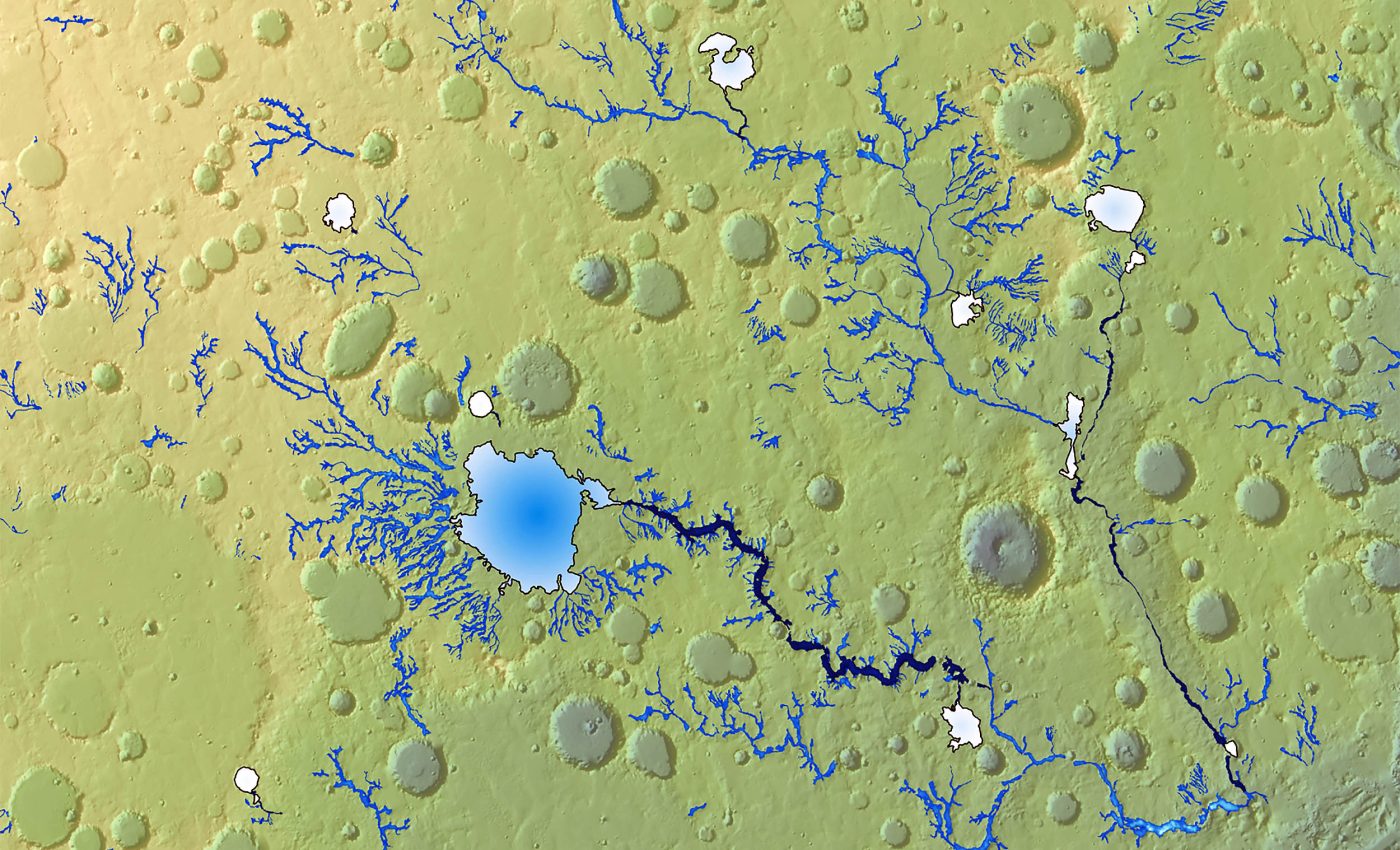

By stitching together previously separate maps of valleys, paleolakes, channels, and sediment fans, researchers have outlined 16 expansive watersheds, each spanning more than 100,000 square kilometers (38,600 square miles).

“We’ve known for a long time that there were rivers on Mars,” said co-author Timothy Goudge, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “But we really didn’t know the extent to which the rivers were organized in large drainage systems at the global scale.”

Mapping Mars’ rivers

Lead author Abdallah S. Zaki, a postdoctoral fellow at UT Austin, and Goudge combed through published datasets of Martian valley networks, open- and closed-basin lakes, and downstream deposits.

They identified 19 major clusters of fluvial landforms. Sixteen of those link up into true watersheds that meet the “large basin” cutoff. Their compilation represents the first planet-wide inventory of Martian river drainage systems.

“We did the simplest thing that could be done. We just mapped them and pieced them together,” Zaki said.

On Earth, large watersheds are common. There are 91 that clear the 100,000-square-kilometer (38,600-square-mile) bar, from Texas’ Colorado River basin to continental giants like the Amazon.

Mars lacks plate tectonics and the high mountain belts that focus runoff into vast basins. As a result, it has fewer large systems and a broad mosaic of smaller drainages.

Even so, the new map shows that when big basins did form on ancient Mars, they mattered greatly.

Sediment movers dominate

The team estimates these large Martian watersheds cover only about five percent of the planet’s ancient terrain. Yet they account for roughly 42 percent of the sediment eroded and transported by rivers.

That imbalance is exactly what river scientists expect. Bigger, longer-lived basins move more water and nutrients over greater distances, creating chemically diverse environments where life could flourish.

Where rivers run long, water interacts with rock again and again, driving reactions that concentrate nutrients and create energy gradients life can exploit.

As Zaki put it, “The longer the distance, the more you have water interacting with rocks, so there’s a higher chance of chemical reactions that could be translated into signs of life.”

Rivers matter as Mars life markers

On Earth, sprawling river systems like the Amazon and Indus are not only ecological hotspots. They’ve been cradles of human civilization.

The logic extends to early Mars. Large basins would have shuttled water, sediments, and dissolved nutrients across wide regions, filling and spilling craters, linking lakes, and carving canyons. These settings offer places where biosignatures could accumulate and remain preserved.

The authors argue that these 16 megabasins should move to the front of the line for future landing sites. They say orbital surveys targeting Mars’ past habitability should focus on them as well.

“It’s a really important thing to think about for future missions and where you might go to look for life,” Goudge said.

Building the atlas

The study didn’t reinvent Martian geomorphology so much as unify it. By tracing connections among known valleys, paleolakes, outflow channels, and depositional fans, the team delineated watershed divides.

The researchers also mapped downstream pathways the same way hydrologists do on Earth.

What remains is to follow the sediment trail: where did the materials from each basin ultimately settle? Pinpointing delta plains, lake beds, or canyon mouths could give rovers high-value targets for sampling layered, water-rich deposits.

Because Mars lacks active plate tectonics, its ancient drainage blueprint likely records a long window of climate history.

The basins’ distribution and linkages can help test competing models for when, how often, and for how long rivers flowed. The new atlas provides the scaffolding for that detective work.

Roadmap for Mars exploration

Taken together, the results shift the conversation from “Were there rivers?” to “How were Mars’ rivers organized, and where did they do the most work?”

That’s a powerful reframing for mission planning. Orbiters can target the newly mapped outlets and sediment traps for high-resolution imaging and spectroscopy.

Landers and rovers can prioritize the same locales for in situ analyses that seek organics, redox gradients, and fine-grained layers that preserve biosignatures.

Mars’ surface tells a story of water that once gathered, linked, and transformed landscapes at scale. By assembling that story into a global drainage map, UT Austin researchers highlighted 16 places where ancient rivers did the heavy lifting.

These locations offer the strongest geological odds of preserving traces of past habitability. The path forward is clear: follow the sediments, decode their chemistry, and let ancient waters guide the search.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–