Modern farming is draining the life from our soils, threatening the global food supply chain

Modern farming has mastered the art of abundance. Through fertilizers, irrigation, and fine-tuned management, we’ve learned how to coax ever-higher yields from the same soil.

However, a new study warns that some of those same choices, repeated year after year, can quietly weaken the soil itself.

Scientists call this property soil resilience – the ability of soil to absorb stress and bounce back to working order. It’s what keeps crops growing through heat, drought, and flood.

When that resilience erodes, the land starts to lose its footing, and recovery becomes harder each season.

Everyday choices change soil

Led by Dr. Alison Carswell at Rothamsted Research, the study traced how everyday farming decisions – plowing, watering, fertilizing, spraying – can build productivity now but chip away at the natural buffers that keep soils stable over time.

“We found that many practices only affect soil resilience with their long-term repeated use,” said Dr. Carswell. The decline often goes unnoticed, surfacing only when fertility drops or structure collapses.

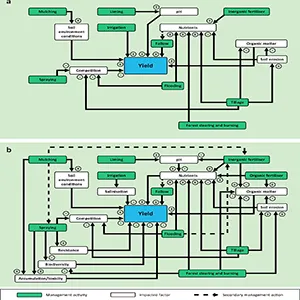

The team framed these processes as feedback loops – chains of cause and effect that either help the land recover or push it further off balance.

When the reinforcing kind takes over, small problems like erosion or pests can snowball into much larger ones.

Soil anchors food and climate

Soils support about 95 percent of global food production, according to an FAO brief. They also store roughly 1,700 gigatons of carbon in the top three feet of ground, a pool larger than all living plants combined, as summarized in a 2023 Global Change Biology review.

A global assessment found that about one-third of soils are already degraded due to erosion, nutrient imbalance, contamination, and other pressures, according to the FAO’s 2015 flagship report.

When farming breaks soil balance

Carswell noted that practices causing soil loss through elevated erosion pose the greatest risk to soil resilience – highlighting inappropriate tillage, forest clearing and burning, and overgrazing of rangelands as primary global threats.

Irrigation saves crops in dry spells, but repeated use of mineral-rich water can leave salts behind. The FAO’s 2024 assessment estimates that about 10 percent of irrigated cropland is salt-affected, a share that could grow with warming and water stress.

Sprays control weeds, insects, and diseases in the short term. With overuse or poor timing, residues can harm soil life, and resistance can spread.

Plastic mulch warms soil and speeds early growth, but when fragments remain, microplastics can build up and alter structure, water flow, and microbial communities.

Healing the ground carefully

Liming acidic soil tends to steady pH near a crop’s comfort zone. When farmers test and adjust on schedule, pH stays in bounds without heavy side effects.

Flooded rice systems can show long-running stability when water, varieties, and nutrients are managed carefully. External impacts still need attention, but the soils themselves often remain productive.

Switches such as conservation tillage, which reduces plowing and keeps residue on the surface, and integrated pest management, which uses scouting, thresholds, and targeted controls, can slow damage. They also demand new habits, precise timing, and patience.

Every tool carries trade-offs. The point is to avoid locking fields into reinforcing loops that are hard to unwind.

Soil forms very slowly. The USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) notes that it can take up to 1,000 years to build just one inch of topsoil – a clock farming can reset.

That pace turns erosion into a near permanent loss on human timelines. It also raises the stakes for choices that strip organic matter or compact the ground.

Farmers learn to adapt

Farmers are already feeling the strain of changing soils. In regions from India to the U.S. Midwest, rising input costs and erratic rainfall are forcing growers to rethink how they treat their land.

Trials with reduced tillage, cover crops, and precision irrigation show that it is possible to maintain yields while rebuilding soil structure and organic matter.

Research at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and similar programs in Africa and Latin America has shown that resilient soils can better handle both economic and climate shocks.

These lessons highlight that protecting soil is not just about ecology, it is about ensuring that future generations can keep farming at all.

Protecting soil from modern farming

Short-term boosts are not the enemy. The risk comes when the same fix is repeated until soils lean on it, then falter if inputs become scarce or weather swings harder.

A practical path is simple to state. Keep soil covered, limit disturbance, match nutrients to need, and protect structure with smart traffic and grazing.

Testing and tracking help. pH, organic matter, infiltration, and compaction tell you if balancing loops are holding tight or slipping.

The broader lesson reaches beyond any single field. Protect the feedbacks that let farming soils absorb shocks, because they are the quiet safety net under our harvests.

The study is published in npj Sustainable Agriculture.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–