Neanderthal superhighways through Eurasia recreated with supercomputers

New computer modeling shows that Neanderthals completed a vast east-west migration across northern Eurasia. They did this in well under two millennia, traveling roughly 2,020 miles (3,250 km), using river valleys as natural highways.

The work suggests their second great migration – from today’s Caucasus region to Siberia – was faster and more predictable than once believed.

The research was led by Emily Coco and Radu Iovita, working with New York University’s Center for the Study of Human Origins and Portugal’s University of Algarve.

The team’s simulations add fresh geographic context to previous genetic hints of a late-Pleistocene Neanderthal migration.

Simulating a 2,000-year journey

The researchers fed a 1 km-resolution map of Late Pleistocene Eurasia – complete with reconstructed rivers, glaciers, deserts, and elevation – into an agent-based least-cost path (AB-LCP) model.

This model simulates human movement across a landscape by mimicking how individuals find routes that minimize travel cost using only local information and incomplete knowledge.

Each virtual “traveler” performed roughly 400,000 Lévy-walk decisions per run – meaning that the choice of the next step or action is not uniformly distributed but is biased towards longer distances or larger changes.

On average, the simulated traveler took 830,000 individual steps while seeking the lowest-energy square in its immediate view. This approach avoids presuming any prior knowledge of the landscape or a fixed destination.

Successful travelers left either the northern or southern flanks of the Caucasus and reached the Siberian Altai in as few as 925,000 to 1.1 million steps. That’s equivalent to about 620,000 miles (one million kilometers) of wandering. This translates to less than 2,000 calendar years of real movement at hunter-gatherer speeds.

Neanderthals followed rivers

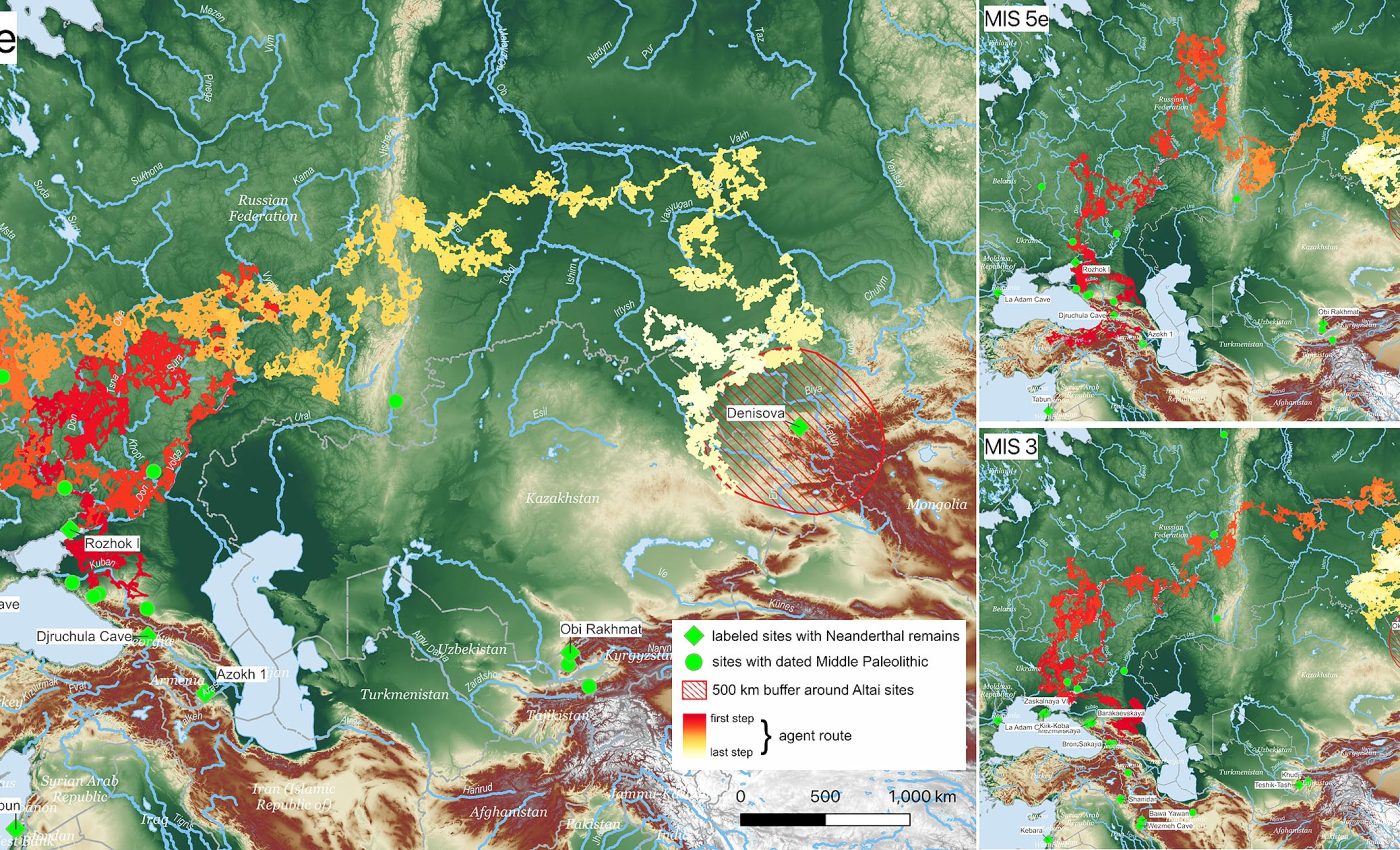

Across dozens of runs, paths clustered along the broad Volga-Kama corridor, slipped through passes in the Ural Mountains, and then funneled eastward along the Ob-Irtysh and Turgai valleys toward the Altai.

Straight-line segments five steps or longer appeared most often inside these river corridors. This confirms that flowing water channels would have drawn mobile bands forward and minimized costly elevation changes.

“Our findings show that, despite obstacles like mountains and large rivers, Neanderthals could have crossed northern Eurasia surprisingly quickly,” Coco explained.

“These findings provide important insights into the paths of ancient migrations that cannot be studied from the archaeological record and reveal how computer simulations can help uncover clues about ancient migrations that shaped human history.”

Warm windows of opportunity

The model succeeded only during two relatively mild climatic windows: Marine Isotope Stage 5e, beginning approximately 125,000 years ago, and Marine Isotope Stage 3, beginning approximately 60,000 years ago.

Warmer temperatures kept glaciers in retreat and vegetation more continuous across the steppe, raising habitat suitability and opening safe crossings of once-impassable rivers.

“Neanderthals could have migrated thousands of kilometers from the Caucasus Mountains to Siberia in just 2,000 years by following river corridors,” Iovita said.

“Others have speculated on the possibility of this kind of fast, long-distance migration based on genetic data, but this has been difficult to substantiate due to limited archaeological evidence in the region.”

“Based on detailed computer simulations, it appears this migration was a near-inevitable outcome of landscape conditions during past warm climatic periods.”

Scattered traces of Neanderthal migration

The preferred northern route runs straight into zones where Denisovans are thought to have lived during the same warm stages.

This lends spatial support to genetic evidence for repeated interbreeding events between the two archaic groups.

Because virtual migrants spent little time in any place they reached, the study suggests why so few Middle Paleolithic sites lie between Eastern Europe and the Altai: rapid movement would leave only scattered, shallow archaeological traces.

No viable southern route

No simulation produced a viable southern detour around the Caspian Sea, challenging earlier hypotheses of a southern Caspian corridor and implying that future surveys should target riverine corridors north of the desert belt.

The authors note that their cost surfaces are static snapshots; adding dynamic vegetation, seasonal ice, or resource gradients could refine future paths.

Still, the close match between modeled routes and the sparse archaeological and genetic record underscores the power of AB-LCP modeling for illuminating the travels of vanished peoples.

Short, fast, and guided by water, the virtual journeys show that Neanderthal migration did not require sophisticated navigation or even a clear goal to traverse half a continent.

Geography – especially the sweep of Eurasia’s great rivers – did much of the guiding for them, turning what once looked like an improbable odyssey into a plausible, almost inevitable trek.

The study is published in the journal PLOS One.