New 3D skull study shows humans evolved faster than any other ape

Every human face hides a long evolutionary story. Behind the curve of the skull and the flatness of the cheeks lies a record of rapid change.

A new study from University College London (UCL) shows that our skulls didn’t just evolve – they raced ahead.

The research reveals that humans developed large brains and flatter faces much faster than any other ape.

Human skulls evolved fastest

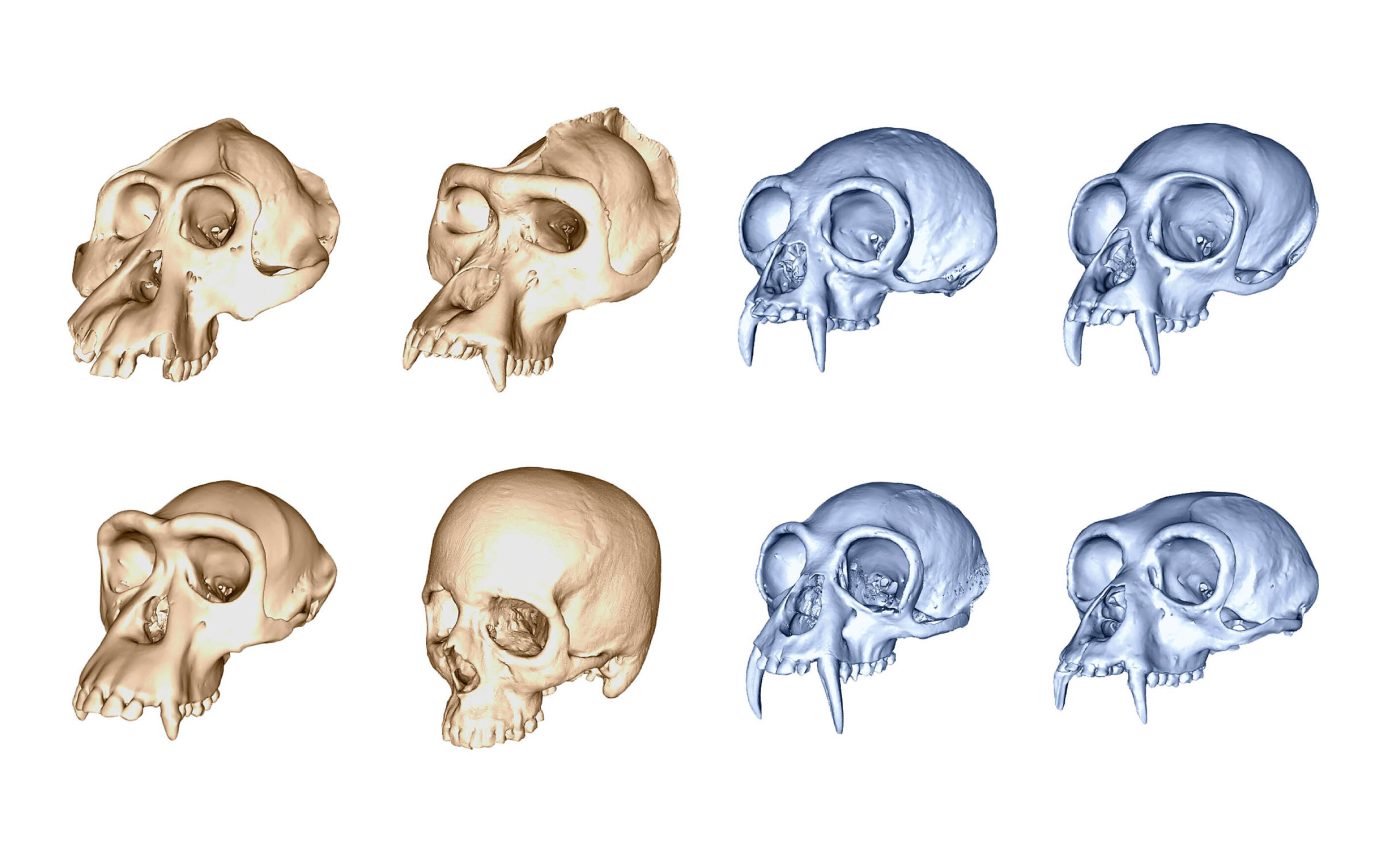

The UCL team built digital 3D models of skulls from seven great ape species and nine gibbon species. They traced how each evolved over millions of years.

The findings were striking – human skulls changed at twice the expected rate. “Of all the ape species, humans have evolved the fastest,” said Dr. Aida Gomez-Robles from UCL Anthropology.

“This likely speaks to how crucial skull adaptations associated with having a big brain and small faces are for humans that they evolved at such a fast rate.

Pressure on skull evolution

According to Dr. Gomez-Roblez, these adaptations can be related to the cognitive advantages of having a big brain, but there could be social factors influencing our evolution as well.

Humans gained rounder skulls and smaller faces while other apes kept longer, projecting features. The braincase expanded rapidly, creating the shape we now recognize as distinctly human.

This acceleration points to strong evolutionary pressure – possibly from both intelligence and social behavior.

New ways of living and thinking

Gibbons split from our lineage about 20 million years ago, yet their skulls remain almost identical across species. That’s not laziness on nature’s part – it’s stability.

Gibbons live in similar habitats, eat similar foods, and follow similar monogamous routines. Their lives didn’t demand major cranial change. This slow pace of evolution helped scientists use them as a comparison group.

In contrast, great apes like humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas faced more varied challenges. Each adapted differently.

Gorillas developed massive crests linked to social dominance. Humans reshaped their faces and skulls, possibly to fit new ways of living and thinking.

The anatomy of change

Researchers divided each skull into four parts: the back of the head, the front, the upper face, and the lower face. They then measured how each section changed through time.

The back of the skull, known as the posterior neurocranium, evolved the fastest. In humans, this region expanded to make room for a growing brain. In gorillas, it stretched upward into crests that signaled power and maturity.

For male apes, skull diversity was higher than for females. That difference likely reflects sexual competition – males needed to stand out, while females faced less pressure to change physically.

Both male and female human skulls evolved faster than expected, but without the same level of dimorphism seen in other great apes.

Humans took a different path

Humans didn’t just change faster; they changed differently. The researchers found that our skulls evolved in a direction that balanced brain size with facial reduction.

The result was a rounder head and flatter face – features tied to advanced cognition and communication. Unlike other apes, humans combined brain expansion with softer facial structures, which may have made social interaction easier.

This pattern wasn’t limited to biology. Social selection played a role too. The ability to express emotion, recognize faces, and communicate may have shaped how the human head evolved.

“After humans, gorillas have the second fastest evolutionary rate of their skulls, but their brains are relatively small compared to other great apes,” said Dr. Gomez-Robles.

“In their case, it’s likely that the changes were driven by social selection, where larger cranial crests on the top of their skulls are associated with higher social status. It’s possible that some similar, uniquely human social selection may have occurred in humans as well.”

Some skulls were frozen in time

Most apes changed little. Gibbons, in particular, show what scientists call evolutionary stasis. Their skulls remained almost frozen in time, shaped by stabilizing selection that resisted dramatic variation.

Despite different chromosomes and occasional interbreeding, their skulls look nearly identical. Great apes evolved more freely, but even then, their cranial diversity was modest compared to ours.

Humans broke that pattern. Brain growth and social complexity acted together, accelerating evolution. Where other species preserved what worked, humans rebuilt.

Human skulls and brains linked

The study uncovered an important split: the braincase and face evolved under different pressures. The brain region adapted to support expanding cognition, while the face reflected environmental and social needs.

Still, in humans, both changed in tandem. Some scientists think this connection marks self-domestication – softer features, calmer temperaments, and deeper social bonds emerging together.

Climate might have played a part too. Variations in nasal and facial shapes could have helped humans survive in different temperatures and humidity levels. Our skulls became versatile – able to balance thinking, breathing, and belonging.

Male and female human skulls

Sex influenced skull evolution in subtle ways. Males among great apes developed more variation, especially in species with strong hierarchies.

Hormones likely extended male growth phases, allowing more pronounced bone structures.

Females reached maturity earlier, limiting cranial change. Humans evolved away from this contrast. Reduced sexual dimorphism meant less physical competition and more cooperative living.

What human skulls reveal

This research paints humans as evolutionary outliers. Our skulls changed quickly and purposefully. Intelligence played its part, but so did society.

Communication, emotion, and connection shaped our heads as much as survival did. Gibbons held steady. Gorillas grew bold. Humans redefined what a skull could be.

Evolution didn’t just make us think – it made us recognizable. In bone and face, it wrote the story of what it means to be human.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–