Scientists are developing a 'pregnancy test' for skeletons

Pregnancy is one of the most profound events in a woman’s life, yet it’s almost invisible in the archaeological record. Tiny fetal bones can be missed or mistaken for the mother’s hand bones.

The hormone most modern tests rely on – human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) – breaks down far too quickly to survive centuries underground.

Now a team of scientists led by Aimée Barlow at the University of Sheffield has shown that bones and teeth can preserve other sex hormones for hundreds to thousands of years.

This bone discovery raises the prospect of a reliable “pregnancy test” for people who lived long ago.

Barlow and colleagues report the first detection of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone in human remains dating from the 1st to the 19th century AD, including women buried with fetuses or newborns.

Pregnancy hormones in bones

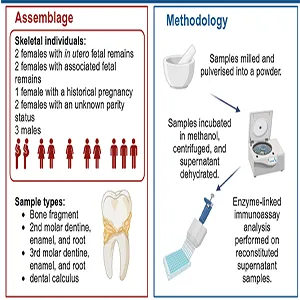

The team sampled rib fragments and a neck vertebra from two men and seven women recovered from four English cemeteries. They also analyzed teeth from those individuals, plus a third man.

In two burials, fetuses were present inside the abdomen; two other women were interred with newborn babies. Sex was confirmed by ancient DNA so the hormone profiles could be matched with confidence.

Each bone and tooth was powdered and treated to extract steroid hormones preserved in minerals and dental tissues.

The researchers then quantified estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone across 74 samples, including different layers of tooth tissue and even dental plaque, which can trap biomolecules as it mineralizes.

Ancient bones and pregnancy

Estrogen proved elusive, appearing only sporadically, likely because it degrades quickly and stores poorly in long-buried tissue.

The strongest signals came from progesterone and testosterone – and, crucially, from their pattern together.

The vertebra of a young woman who died carrying a full-term fetus (11th–14th centuries) showed strikingly high progesterone, a hallmark of late pregnancy.

Another woman from the 18th–19th centuries, also thought to be in her third trimester at death, had elevated progesterone in her rib.

The dental plaque of two women buried with babies (5th–6th centuries) contained moderate progesterone as well. Those findings fit basic biology: progesterone surges during pregnancy and around birth.

The hormone that went missing

Equally telling was what the researchers did not find. In all four pregnancy-associated cases, testosterone was undetectable in bone and tooth tissues.

They found a single trace only in the plaque of a woman buried with a premature infant.

By contrast, three women not linked to fetuses or infants – one from the Roman period and two from an 8th–12th-century cemetery – showed testosterone in their ribs and across tooth layers.

Taken together, those signals point to a promising biochemical signature: elevated progesterone coupled with a testosterone “drop-out” in the same individual.

If validated at scale, that combination could flag pregnancies and immediate postpartum states in archaeological remains with far more certainty than visual inspection alone.

Giving voice to buried mothers

A reliable hormone-based test would transform how researchers reconstruct past lives.

It could reveal how often people died while pregnant or shortly after birth, whether birth seasonality changed across eras, and how famine, disease, or social status shaped pregnancy risk.

It could also help researchers explain burial choices – why some women were interred with infants and others were not – and refine demographic models of ancient communities.

“These techniques could be used to detect pregnancy in skeletal remains more reliably and so give us more accurate insights into ancient pregnancy.”

Beyond data, the approach promises a more humane reading of the past: a way to see intimate biological experiences etched into tissue, rather than inferred from artifacts.

Where the research goes next

The authors are careful not to overstate their case. Estrogen’s poor preservation complicates interpretation.

Some male bones and inner tooth layers showed moderate progesterone, a background signal that needs explanation.

Burial environment, time since death, and tissue type likely influence which hormones persist and at what levels.

Researchers must test any threshold used to label a sample as “pregnant” across large, diverse datasets to avoid false results.

Future work will need modern reference collections to calibrate pregnancy stages against hormone levels in different tissues.

Moreover, broader archaeological samples spanning climates and soil chemistries are also necessary.

Finally, scientists should look for additional biomarkers that can corroborate steroid signals. If researchers can time postpartum changes in bone and tooth, they could tell pregnancy from recent childbirth.

Bones that remember lost lives

For now, the proof of concept is compelling: bones and teeth remember more than anyone expected.

Within their mineral lattices, a faint chemical ledger survives. It can record a late-term surge of progesterone – or a subtle ebb in testosterone – and with it, the presence of a life not yet born.

If validated, this approach could finally bring pregnancy, childbirth, and pregnancy loss into the archaeological story, restoring voices too often missing from the deep human past.

The study is published in the Journal of Archaeological Science

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–