Scientists crack the 2,000-year-old mystery of chameleons’ eyes

For more than 2,000 years, people have watched chameleon eyes swivel around and wondered how they pull it off without twisting their necks.

Now high-resolution scans have finally revealed the secret: each eye is wired to the brain by a long, tightly coiled nerve that acts like extra cable hidden inside the skull.

Those spiral cables let the eyes sweep across almost the whole surroundings while the head stays nearly still, a huge advantage for an animal that hunts from narrow branches.

The discovery comes from a team working with preserved specimens in natural history museums, and it shows that chameleons solved a vision problem in a way no other known vertebrate has.

How chameleon eyes move

Chameleons have long fascinated biologists because their eyes seem to move on their own, scanning for insects and danger at the same time.

The work was led by Juan D. Daza, an associate professor at Sam Houston State University whose research focuses on how reptiles evolve unusual body plans for life in complex three dimensional habitats.

“Chameleon eyes are like security cameras, moving in all directions,” Daza. Detailed work has shown that the eyes scan separately at first, then coordinate when the animal locks onto a target.

Their vision sets up an equally extreme feeding style. One study on tiny chameleons showed their tongues reaching more than twice body length with accelerations among the highest measured in any reptile.

That spring powered system lets even thumb sized species snatch insects in a fraction of a second.

Coiled nerves behind the eyeballs

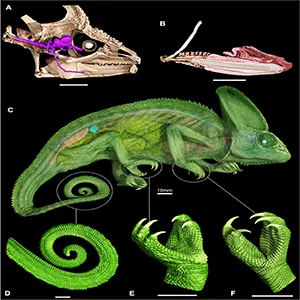

When Daza and colleagues examined digital skull models, they saw something no one had clearly described in any lizard before.

Each eye connects to the brain through a long optic nerve, a thick cable of nerve fibers carrying visual signals to the brain, that loops several times before reaching the eyeball.

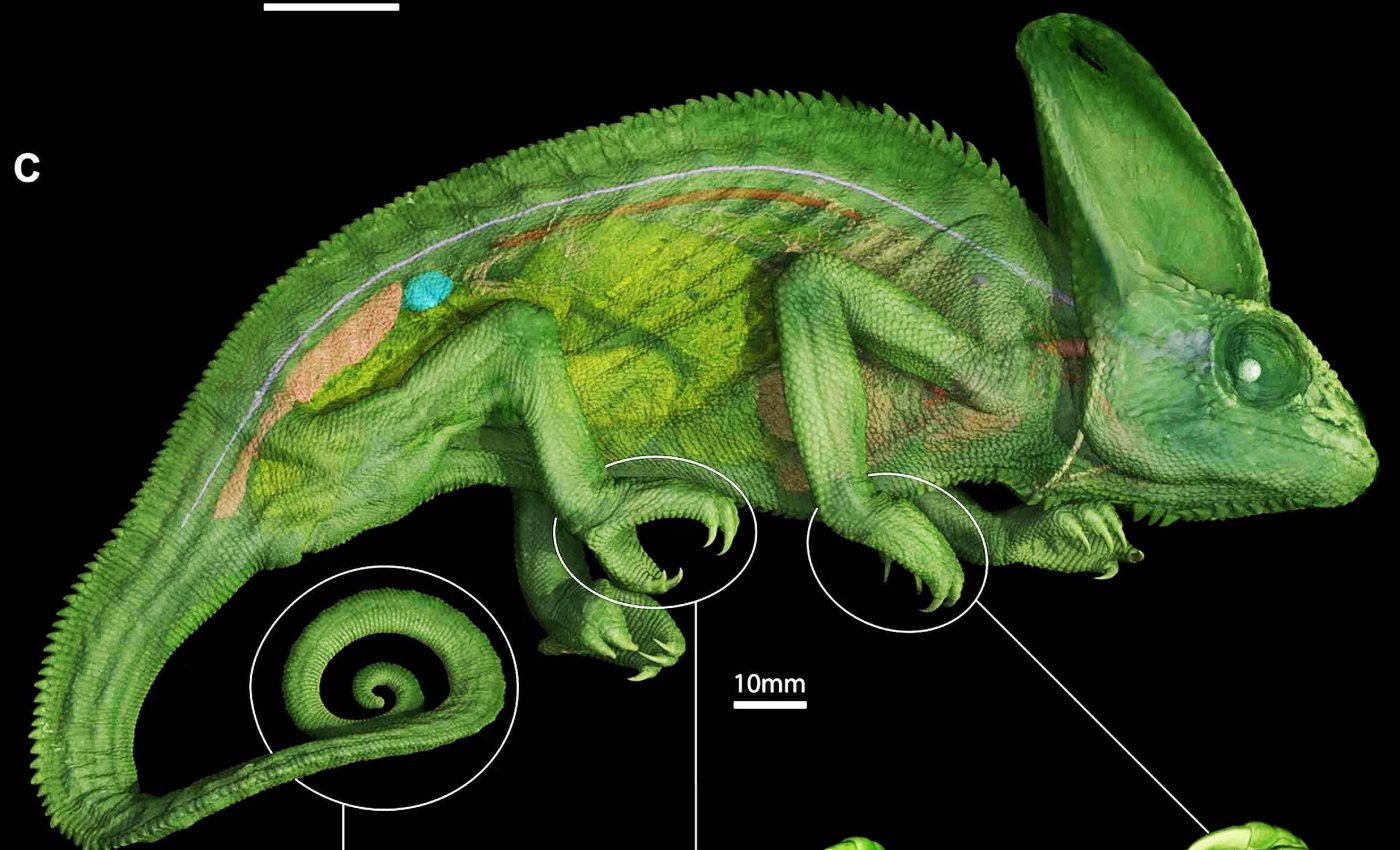

The new research used contrast enhanced CT scans to compare three chameleon species with more than thirty other lizards and snakes.

Chameleons alone had optic nerves that were far longer than the straight line distance from brain to eye and followed a sinuous, telephone cord like path through the skull.

In adult veiled chameleons, that path contains sharp bends and S-shaped turns, so the nerve length can be nearly twice or three times the simple gap between the chiasm and the eye.

Most other reptiles in the study had nerves only slightly longer than the direct distance, with gentle curves rather than tight loops.

The team also tracked how this structure forms in embryos of the veiled chameleon. Early in development the nerves are short and straight, but they grow longer, then buckle into loops so that hatchlings emerge with fully coiled cables and already mobile eyes.

Stiff necks and tree life

Chameleons are classic arboreal lizards, meaning they spend most of their lives in trees, with grasping feet and a prehensile tail that help them cling to narrow perches.

Their bodies are deep and laterally compressed, and their careful, slow walk trades speed for stability high above the ground.

Many animals with big eyes expand their view by moving the head or neck. Owls and some lemurs swivel their necks through huge angles, while humans and rodents rely on somewhat stretchy optic nerves and wavy fibers that give a little as the eyes turn.

Chameleons went in a different direction. Their neck vertebrae are shortened and locked together in ways that reduce side to side bending, making the front of the body relatively stiff compared with many other lizards.

The coiled optic nerve seems to offer a mechanical solution to that stiffness, providing slack so the eyes can rotate through very large angles without yanking directly on the nerve.

Similar tight coils have only been reported in a few invertebrates, such as stalk eyed flies, which also carry their eyes on long movable structures.

Why scientists missed the coils

The strange eye movements of chameleons caught attention long before CT scanners existed. Aristotle even proposed that they had no optic nerves at all, while later writers disagreed over whether the nerves ever crossed from one side of the brain to the other.

By the seventeenth century, anatomists were drawing diagrams that came close to the true layout, yet the coils still stayed out of sight.

Later dissections in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries sometimes clipped or shifted the delicate nerves, leaving only partial curves that no one interpreted as full spirals.

Researchers noted that people have examined chameleon eyes for centuries because they draw so much attention, yet physical dissections often destroy the very structures needed to understand how the eyes work.

They explained that cutting into the animal can remove information that reveals the full story behind its vision.

CT scans change everything

Modern CT scanning makes it possible to study entire heads without a single cut. With the right contrast agents, even soft tissues such as nerves and the brain can be traced inside decades old specimens.

A large collaborative network has already turned thousands of preserved specimens into downloadable 3D models for anyone to inspect.

Many of the chameleons in the new optic nerve study were part of this project, which links museums across the United States.

During a visit to the lab, a researcher noticed the first coiled nerves in a tiny leaf chameleon that had been scanned.

That unexpected find pushed the team to review older datasets and gather new scans from other lizards and snakes to see whether the coils were common or limited to chameleons.

“These digital methods are revolutionizing the field,” said Daza. He emphasized that the same specimens can now be reexamined many times without any further damage.

Lessons from chameleon eyes

The fossil record does not yet show when chameleons evolved their coiled nerves. The oldest known fossils already have many of the tree living features seen today, so the order in which traits like grasping feet, ballistic tongues, and spiral nerves appeared remains uncertain.

Even among living reptiles, it is unclear how unique the chameleon solution really is. Other large eyed, tree dwelling lizards, such as some giant anoles, might also benefit from extra slack in their visual wiring, but their cranial anatomy has not been mapped in similar detail.

The team also wants to understand how much extra eye rotation the coils actually allow compared with straighter nerves in related species.

Biomechanical models that treat the nerve as a flexible cable, along with new measurements of eye movement in live animals, could help answer that question.

However those tests turn out, the study shows how reexamining familiar animals with new tools can still reveal hidden structures.

A problem that puzzled thinkers from Aristotle onward now has a concrete anatomical answer tucked just behind the eyes of a patient lizard watching the world from a branch.

The study is published in Scientific Reports.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–