Small reptile covered in spines turns out to be a new species of gecko

A small, spine covered lizard seen on a temple wall in southern India was determined to be a new gecko species – Hemidactylus quartziticolus.

Researchers confirmed the discovery in a peer-reviewed paper and the animal measures under 3 inches from nose to tail base.

The gecko lives on quartz rich hillocks near Thoothukudi in Tamil Nadu, a dry corner of India’s southeast coast. Fieldwork showed the species perched on rock faces and, at times, on temple masonry.

Inspecting Hemidactylus quartziticolus

The team worked on narrow ridges of quartzite in scrubland and noted several look alike lizards in a short span of time. Quartzite, a hard rock formed when sandstone is squeezed and heated, dominates these low hills.

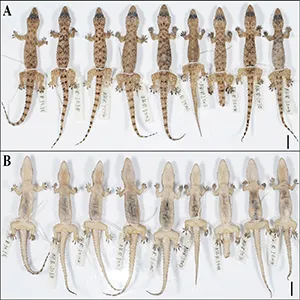

Close inspection of Hemidactylus quartziticolus revealed a tan brown gecko with dark X-shaped blotches and a back armored in short spines. The spines are tubercles, small raised scales that form tight rows and give the skin a pebbly texture.

Lead researcher Akshay Khandekar from the Thackeray Wildlife Foundation in Mumbai (TWF), coordinated the effort and analysis.

Khandekar is a taxonomist, a scientist who names and classifies species, with recent work cataloged by NCBS’s collections team presenting the discovery.

How they knew it was new

The team used integrative taxonomy, a method that combines DNA evidence with body measurements, to test whether the lizards matched any known species. They compared scale counts, pore patterns, and toe pad features with close relatives.

Genetic tests focused on ND2, a mitochondrial gene used to compare closely related species. The results showed strong separation from all sampled relatives, consistent with a distinct lineage.

Numbers from the lab backed up what the eyes suggested in the field. Males have a continuous band of precloacal femoral pores rather than two broken series, and there are 18 rows of enlarged dorsal tubercles across the midbody.

Hemidactylus quartziticolus appearance

This new gecko is small but looks tough. Its body carries knob like spines along the flanks and tail, with females tending toward pinkish brown and males appearing darker.

Most individuals were seen a couple of feet above ground on lichen stained rocks. Several were found after rain, a timing pattern that often suits rock dwelling geckos in dry landscapes.

“Hemidactylus quartziticolus sp. nov. is one of the most morphologically distinctive among brookiish congeners,” wrote Khandekar. That distinctiveness comes from the dense spines and the uninterrupted line of pores.

These quartz hills sit inside thorny scrub known to locals for hardy grasses and goats, not rare wildlife. The study site lies on low ridgelines with loose stones and sparse bushes.

Despite that reputation, the team found the gecko at two separate hillocks about 28 miles apart, which signals that similar hills might hold more surprises. The authors urged more night surveys in the dry zone where rocky slopes remain understudied.

India’s scientists keep adding to the country’s species list each year as new surveys reach overlooked habitats. In 2023 alone, a national report logged hundreds of animal discoveries across the country.

What the find tells us about geckos

Hemidactylus quartziticolus geckos come in many shapes across peninsular India, and small, tuberculate species with X marks are often grouped as brookiish geckos. This newcomer falls near that cluster but pushes the look to an extreme.

Dry rock outcrops have produced several unusual relatives in recent years, including two species with bright yellow tails from the Deccan plateau. That study documented how rocky islands on land can shelter distinct lineages.

The team recorded the gecko only on rock faces and nearby walls, not in houses or farmland. That narrow footprint raises questions about type locality, the exact place a species is first defined, and whether other hillocks in the region hide related forms.

From surveys to names

The gecko’s scientific name, quartziticolus, points to its home on quartzite. The suggested common names are quartzite brookiish gecko and Thoothukudi brookiish gecko.

The species can be told from neighbors by a tight set of characters that work together rather than alone. Those include the 18 rows of dorsal tubercles, the continuous pore series in males, and the small lamellae counts under the first and fourth toes.

Lessons from Hemidactylus quartziticolus

Vallanadu and Kurumalai, the two known sites, are low elevation and close to roads and settlements. Yet they supported gravid females during the survey window, a hint that these hills host core breeding habitat.

Finds like this reshape where scientists look next. Dry scrub may seem ordinary at first glance, but at night those rocks can carry lineages that slipped past earlier surveys.

The authors argue that more climbs and headlamp checks on scattered hillocks could reveal other hidden geckos. Careful work in these places can move species from rumor to record, then into conservation plans built on data.

The study is published in Vertebrate Zoology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–